A prayer to Iemanjá: The collapsing fisheries of northeastern Brazil

Story by Barron Bixler + Allison Carruth • Photography, videography + design by Barron Bixler

Pontal do Coruripe, in the northeastern Brazilian state of Alagoas, is nestled between nutrient-rich mangrove swamps at the mouth of the Coruripe River and a natural sandstone reef that protects its fishing harbor.

Its ideal geography has made this remote coastal village an important center for commercial fishing and shrimping.

pontal do coruripe

With a population of a couple thousand residents, Pontal do Coruripe sits at the mouth of the Coruripe River, with a commercial fishing harbor tucked behind a natural sandstone reef.

mangrove swamps

Mangroves serve as the nursing ground for countless species of marine life. In Brazil, as well as globally, they're under threat from pollution, land development, aquaculture and sea level rise.

harbor

Intermingling nutrient-rich fresh water and seawater, Pontal's protected harbor provides a crucial spawning ground for marine life, including commercially important species of fish. In Pontal, subsistence fishing in the harbor, which targets juvenile fish, has contributed to the region's fishery collapse.

the atlantic

30 years ago, Brazil's aquamarine Atlantic waters were believed to be underfished. But decades of overfishing, destructive bottom-trawling and poor fisheries mismanagement have caused populations of high-value commercial species to teeter on the brink of collapse.

A subsistence fisherman working the shallows of the harbor holds a juvenile fish caught in a net

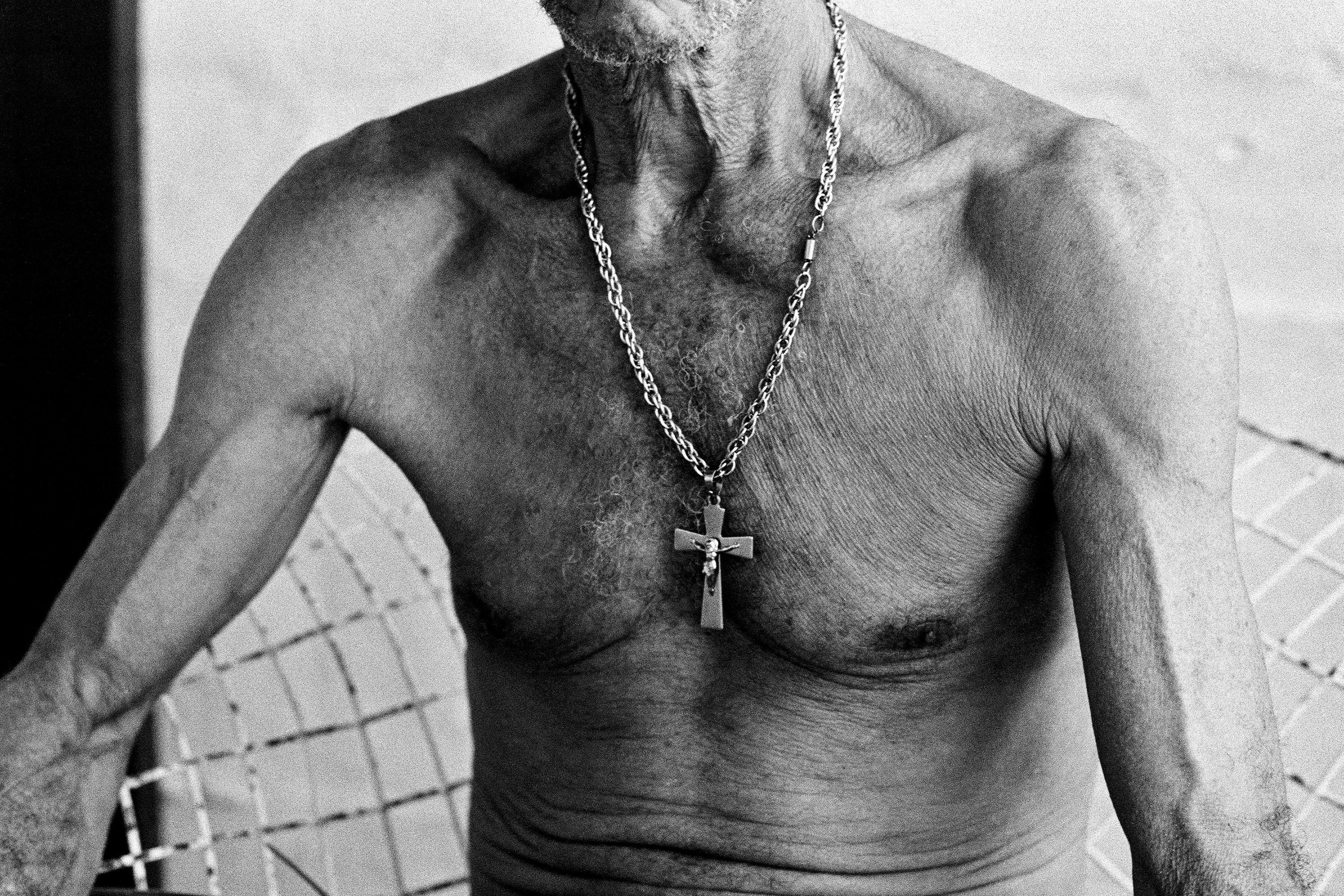

For generations, artisanal fishing has been the way of life in Pontal.

Before Brazil's fishing fleet modernized, most fishing was done on jangadas—traditional wooden rafts with sails.

With the advent of arrastões—double-slung diesel-powered trawlers—in the 1970s and 1980s, Pontal's fishermen could venture out to sea for days at a time and bring back bounties of large, valuable species like lobster, shark, tuna, swordfish, bluefish, grouper and jack.

Regional and even global markets for their catches sustained their families and neighbors and supported a thriving, tightly-knit community.

But over the past 25 years, Pontal's relationship to fishing has been upended, leaving the village's people questioning what the future holds.

Familar rhythms

In Pontal, days begin and end much as they have for as long as anyone can remember.

At 4am, fishermen silently set out by foot or bike through the crooked streets and alleys down to the harbor where they're ferried out to their trawlers. Before their families wake, they're already miles out to sea, many of them for days.

Out of the pre-dawn quiet, sunrise brings a steadily building soundscape. Roosters crow. Men start to hammer on boats not yet seaworthy. Horse-drawn carriages creak under the burden of transport. Distant mopeds whine like mosquitoes. Through open windows, kitchens burst to life with the heavy clang of metal on metal and the voices of mothers, mostly, directing children through their morning rituals. A multiverse of whispers erupts into boisterous conversation—debate, laughter, anger, along with tender words of love, worship and gossip.

From there, the day ebbs and flows. People with jobs not in fishing scatter from their homes and reabsorb into the few shops and restaurants in town, the harbor, construction sites, the sugar cane and coconut plantations that flank Pontal to the north along the coastline. Many women gather to talk and make handicraft—mostly baskets woven from dried palm leaves and strips of colored cellophane—which can generate significant income.

As the afternoon heats up, things quiet down.

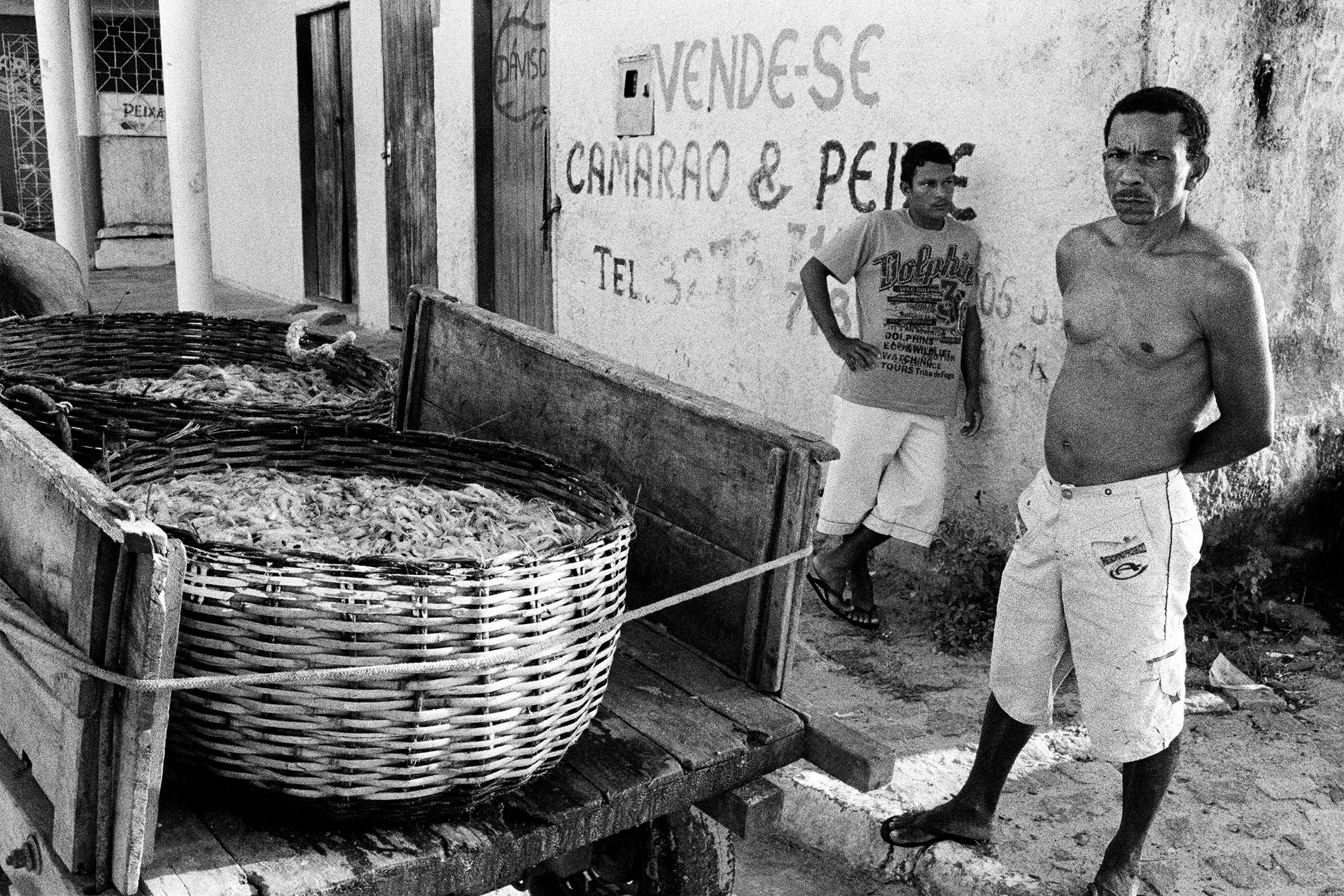

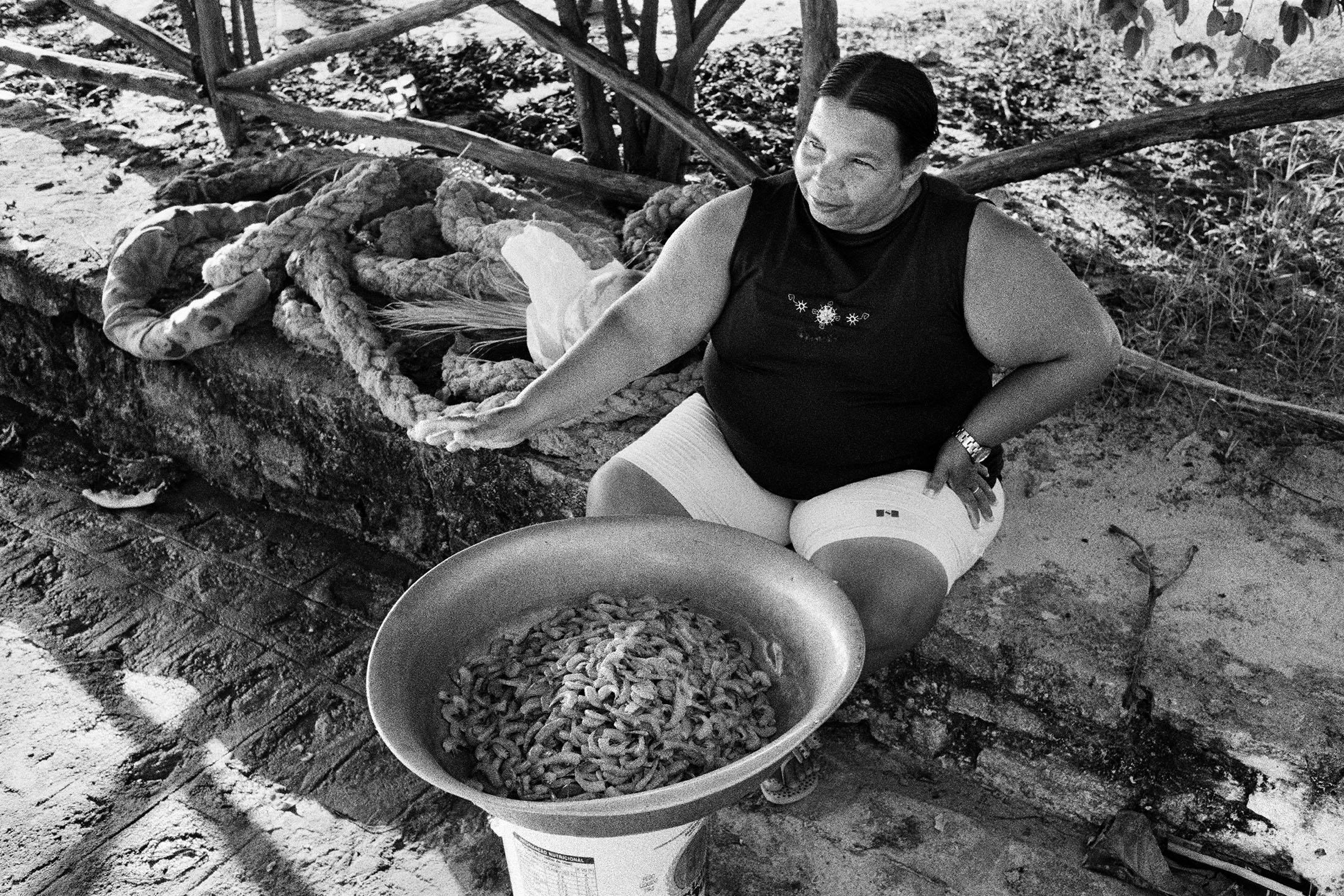

And then in the late afternoon, as the diesel-powered day trawlers thunder into the harbor, the waterfront reanimates. Friends, wives, daughters, sons, brothers and horse-drawn carts all wade into the water to help carry the day's catches to the weigh station. Wet plastic sacks full of small fish, still thrashing, are passed around, with everyone who helps out getting a share. After being sorted, some shrimp go to the smokehouse, some get put on ice and taken to the fish market in the main town of Coruripe, some go into pots and become that night's moqueca de camaroes. Buyers, sellers and distributors of seafood hover, waiting for the good stuff: lobster mostly, and the rare prize fish.

Having come of age under this dark cloud, the children and grandchildren of the old-timers aren't as burdened by nostalgia or remorse. They have lives to build, families to feed and few options.

Alagoas, where Pontal sits, is Brazil's third-poorest state. It has a poverty rate of 50 percent. Urban service-sector jobs drive the state's economy, with agricultural jobs—mostly on sugar cane and coconut plantations, ghosts of the area's brutal colonial past—accounting for most of the available work in non-urban areas.

Few young people want to leave, or can afford to leave, in search of other kinds of work. Pontal's mythos as a place of fishing and fisherpeople still exerts a strong pull. Fishing has provided generations not just income and assured subsistence through hard times, but more crucially a sense of identity and belonging, of independence and pride.

What happened?

Brazil's wider crisis of fisheries mismanagement

In the 1990s, many of Brazil's artisanal and commercial fisheries—including those based in and around Pontal—suffered a troubling decline. By the early 2000s, populations of many high-value target species teetered on the brink of collapse, and even extinction. Twenty years later, the problem persists.

So what happened?

In the simplest terms, Brazil's Atlantic waters have been intensively overfished.

But Brazil's fisheries have also been intractably mismanaged. Less than 10 percent of the 25,000 fishing boats registered by the Brazilian government are monitored by satellites. This regulatory blindness facilitates illegal fishing by both Brazilian and foreign-based fleets, including industrial fishing vessels sailing from Venezuela, China and Japan.

Brazil collects almost no data on its fisheries and what data it does collect it doesn't share with the public or cooperative international monitoring initiatives.

Less than 7 percent of the 117 coastal species fished in Brazil have a known status of stocks. The government has not known what and how much has been taken from the ocean since 2011.

A study published in 2017 by the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences places the country 26th in a ranking of 28 major fishing nations based on efficiency. Brazil is only ahead of Myanmar and Thailand.

37 target species are being overfished in Brazil, including...

bluefin

grouper

crevalle jack

atlantic mackerel

southern atlantic red snapper

The new target species are more abundant, smaller and stranger

beltfish

conger

gray triggerfish

union leatherjacket

atlantic bigeye

sharks

dophins

rays

crabs

turtles

Visible from space, sediment plumes from bottom trawling reveal intricate patterns of seafloor damage

Image courtesy of SkyTruth

Shrimping nets for fishing

In Pontal, as diesel-powered trawlers became ubiquitous, fishing nets got larger while their meshes got smaller—partly to target shrimp as well as fish. These technological advancements allowed the fisherman to intensify their operations and cover more ground, plumb deeper waters and gather ever more fish.

But the small-mesh shrimping nets keep juvenile fish from escaping as they're able to with better net designs, as illustrated in this video by SafetyNet Technologies.

Global appetites

Who—or what—is responsible for Pontal's story?

The fishermen we interviewed didn’t mince words: "it is not a crime of the nets; it is our crime." The decline of fisheries and the difficulties of fishing today are, through this lens, the consequence of thousands of individual decisions—to jettison the jagandas and adopt trawling, to chase new markets, to give up subsistence economies.

But that story opens onto others that implicate people and places far from Pontal.

For centuries, northeast Brazil has been place where outsiders have mined the land and trawled the sea—driven by appetites for both the resources and flavors of far-away places. In our time, those global appetites have made the region where Pontal sits a target of international fishing and oil and gas extraction. Those forces converged in 2019, when crude oil blanketed over 2,200 miles of the northeastern Brazil coastline—the largest such spill in the nation's history. The disaster damaged the coast's mangrove forests and intertidal ecosystems, accelerating the decline of fisheries. Media coverage of the spill featured a photograph of the Pontal beach covered in oil. A year later, at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ministry of the Environment announced that a controversial proposal to build a shipyard for oil tankers in Pontal was officially defunct.

There are also more banal, quotidian ties between Pontal's story and the world beyond. Those ties are visible in the rise of evangelical churches; in the omnipresence of satellite dishes and mobile phones; in the Japanese-owned Netuno geladeria (or ice house) that cleans, packs and freezes shrimp from nearby aquaculture operations for international export.

Then there are our appetites for the fruits of the sea—a siren song for the fishermen in places like Pontal. Those appetites fly in the face of the ecological realities that the ocean has been pushed to a breaking point. For the specter that looms behind the story of local overfishing and the larger histories behind it is that of climate change. And the lived experience of Pontal at once testifies to the reality of climate change and demonstrates that there are no simple solutions. Today, our world is awash in grand designs for seawalls and managed coastal retreat, and, too, in movements for just transitions. The story of Pontal cautions against either technological fixes or activist sea-change untethered from the complex lives and struggles of those who are on the frontlines.

The uncertain future of Pontal is also ours.