An original audio story series led by Jayme Collins

You can find Archival Ecologies on Apple Podcasts, Spotify Amazon Music and iHeartRadio.

Archival Ecologies is an audio story series created and produced by Jayme Collins as a companion to a book project. The series investigates how ecological events and natural disasters are affecting cultural collections and the artifacts and memories they preserve for diverse communities. As climate change leads to more extreme weather events, the interactions between archives and the environments where they reside are becoming more frequent and more fraught. Beset by floods, fires, mold blooms and other ecologies, the objects and documents that communities preserve are sometimes lost or damaged.

This series tells the stories of such archives, their stewards and their significance for communities at the forefront of climate change. What do objects and collections mean in the communities that steward them, and what does recovery from loss look like? How do cultural stories continue or change in the absence of objects and collections? Archival Ecologies will address these questions by exploring the ecological lives of cultural collections in states of disruption, documenting collections in crisis and researching their connections to geographies and histories. Each season will take listeners to a new environment to share community experiences of why archives matter, what their loss means and what recovery might look like.

Credits

Created and hosted by Jayme Collins with research, writing and production support from Jamie Rodriguez, Kavya Kamath and Molly Taylor. Music by Hamilton Poe. Sincere thanks to Kouvenda Media for their partnership on this project. A production of Blue Lab with support from Princeton University. Copyright 2023 Jayme Collins and Blue Lab.

Season 1: Fire in Lytton

You can find Archival Ecologies on Apple Podcasts, Spotify Amazon Music and iHeartRadio.

During the 2021 summer heatwave in the Pacific Northwest, the historic town of Lytton, BC and nearby First Nations reserves suffered a catastrophic wildfire that took local archives, museums and cultural collections with it. In this first season of Archival Ecologies, we’ll tell the stories of those collections and the communities who have stewarded them. Through the voices of those cultural stewards and knowledge keepers and the objects that have been lost (or salvaged), we’ll explore the interwoven histories and geographies of the region and the larger intersections between climate change, cultural preservation and recovery.

Episode 1: In the Burn Zone

Archival Ecologies Episode 1: “In the burn zone”

Full Transcript

JAYME: This is a ceremony to bless the ground. Lytton residents take turns scooping gravel from a mound and pouring it into a hole a few yards below. Two years ago today, on June 30 2021, a fire started by the railroad bridge just south of this site. Most of Lytton burned down. Hundreds of people lost their homes, and two died. Each person hands the shovel off to another. Most hesitate before releasing the gravel, pausing over the ledge to say a prayer. Some people drive the shovel upward so the gravel lifts in the air before it falls. Others simply rotate the handle, letting the gravel fall softly down from the blade.

ERNIE: It's like a funeral. You go to a funeral, you're throwing the dirt. You’re saying your final goodbyes to your loved one. Today that’s what we're doing. We're burying old Lytton.

JAYME: Just before blessing the ground, the community held a prayer walk through town.

We passed empty lots closed off by blue wire fences—two years after the fire in Lytton, nothing has been rebuilt. There’s some debris, but most lots have been cleaned, exposing just a concrete foundation or a hole where a building used to be. Only a few details indicate there was a fire: charred trees and lamppost shades that look like melted candles. It took ten minutes to reach the end of Main Street, where around 60 people have gathered on a gravel site for speeches and prayers. It’s dry hot, 33 degrees celsius, 92 Fahrenheit, and there’s a tent for elders and kids, but most stand in the sun. To the west, the site slopes down to the Fraser River. On the mountainside overlooking Lytton from the east is the railway. Its trains are running constantly during the ceremony.

JAYME: There’s a range of speakers. They’re from a disaster relief organization in Vancouver, the Anglican Church in Lytton, the Buddhist community in the neighboring Botanie Valley, and the Nlaka'pamux nation.

AMY: [prayer]

JAYME: This prayer by Amy is in Nkala’pamux, an endangered language that community members are actively working to teach and learn. Another Elder, Pauline, also offers a blessing.

PAULINE: I ask the water to protect and to hold all our people. That soonall our people come back home and we can all be together again. I love all of you and I can't wait for that day to come and we can have our community back home again.

JAYME: Most residents still haven’t been able to return to Lytton. Today, community members are coming from where they've been staying since the fire—places like Lillooet and Chilliwack and Kamloops, which are all at least an hour away. For the past two years, recovery has been mired in a series of government regulations and procedures. There was a lengthy soil remediation after the fire baked heavy metals into the dirt. Then there was an archaeological survey in search of artifacts from the First Nation people who lived there before it was Lytton. New net-zero building requirements demand approvals and inspections and high costs that most residents can’t afford.

After the fire, Mayor Denise O’Connor was elected on a platform to speed up recovery. At the ceremony, she shares a welcome update:

DENISE: We have all the approvals now to start the backfill, which means next week we're going to have backfill happening in the village here, so yeah, pretty exciting…

JAYME: Today, it’s clear that the blessing of the ground means several things at once. Some people hope for the return of the old Lytton; others look forward to a new community. Father Angus, from the Anglican church, invites community members to help “fill the holes” that were left by the fire.

ANGUS: Creator of all, you stand, you call us to stand together here today to fill the holes of the past with clean soil and water, the building blocks of a new community.

JAYME: Two years after the fire, the Lytton community is still figuring out how to recover. Part of the challenge has to do with the scale of the loss: not only were homes and buildings destroyed, but so were building codes, town bylaws, community centers, parks, archives, and museums. What does a community do when it loses everything from physical infrastructure to government documents, community gathering places, and cultural objects? How does it recover its culture and community, and chart a path forward?

This is “Archival Ecologies,” a new audio story series about cultural collections like archives and museums in states of disruption—when they are burned by a fire, flooded by a storm, or invaded by insects or mold. We’ll look at collections from across the world, in places like British Columbia, Northern Europe and the South Pacific, where ecological forces have reshaped collections and transformed their role in culture. The show is produced by Princeton University’s Blue Lab and led and hosted by me, Jayme Collins. This season, we’ll be telling a story of Lytton, a small town in the Fraser Canyon region of British Columbia that lost culturally significant collections when it burned to the ground in a 2021 heatwave-fuelled wildfire.

Archives can be many things: they can be official collections of documents and books, the kind of thing you might expect to find in a capital city or a university, or they can exist in museums and art galleries. But they can also be in people’s homes, in a living room or basement, or even in a personal notebook of observations and quotations. We might even think of the soil underneath buildings as an archive, a collection of physical, chemical, and cultural information about what has been there in the past. Archives can take many forms, but as collections of objects, documents, and other information, they provide the scaffolding for stories that carry meaning and cultural identity. In many different ways, archives are places where people turn to find identity and tell stories about who—and where—they are.

So how do communities grapple with the loss of objects and documents that let them tell stories about their culture? What happens to cultural identity when the objects and spaces that hold stories are lost or damaged?

PATRICK: Lytton first and foremost represents a form of identity. It's who I am

JAYME: This is Patrick Michel. He’s the retired chief of the Kanaka Bar Indian Band, which lies about a 15 minute drive down the river from Lytton. Patrick has lived in Lytton his whole life and lost his house in the fire.

PATRICK: To me it is a place, a geographical place that has provided my family with sustenance for more than 8,000 years. And while I, I can't say and speak beyond what I know in my own lifetime. What I am though is a product of 8,000 years of learning. So sometimes I'll speak about things that might have happened a thousand years ago, right? I remember when Simon Frazier arrived on June 20th, 1808. Why? ’Cause the stories that were told to me, weren't told to me, was told to my grandmother by her grandmother who was alive at the time. So what happens is it's really hard for me to separate out traditional stories that are handed down from real life experiences. So Litan becomes identity. It's, it's who I am, it's who my family is. So I, I didn't know if I can articulate anymore in that other than it's, it's my home.

JAYME: Lytton is a small village about three and a half hours northeast of Vancouver. The town’s located at the confluence of the Fraser and Thompson rivers in a canyon that’s windy and arid. During the summer it can get quite hot. The Nlaka’pamux have inhabited the land for at least 7000 years. European settlers arrived in the area when Simon Fraser traveled down the river in 1808. Near the middle of the century, the area’s population boomed during the gold rush. After mining activity waned, settlers flocked to the area again around the turn of the 20th century. This time they came to build the railways. Before the fire, Lytton was officially the home of 210 residents. With the closest town nearly an hour away, thousands more relied on the town as a source of community.

MEDIA CLIPS: We do begin with the latest on a wildfire disaster in British Columbia. Its in the community of Lytton. // The town of Lytton was engulfed by flames. // Nearly 90% of the village burned to the ground. Its been a summer of devastating wildfires. // Devastating wildfires that tore through the village. // My hometown lost in less than an hour.

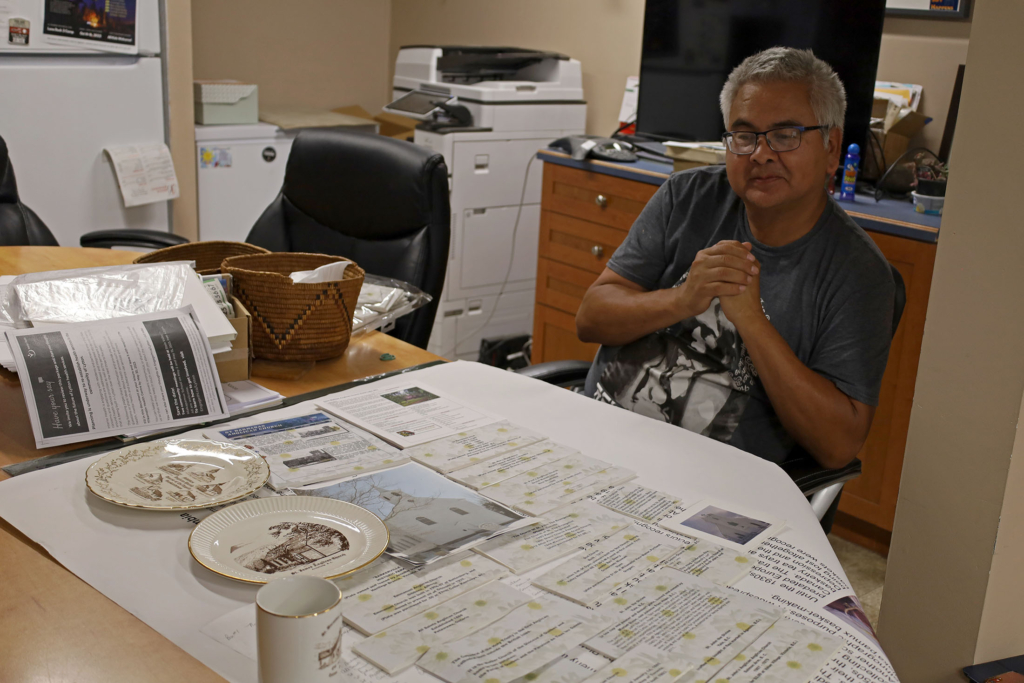

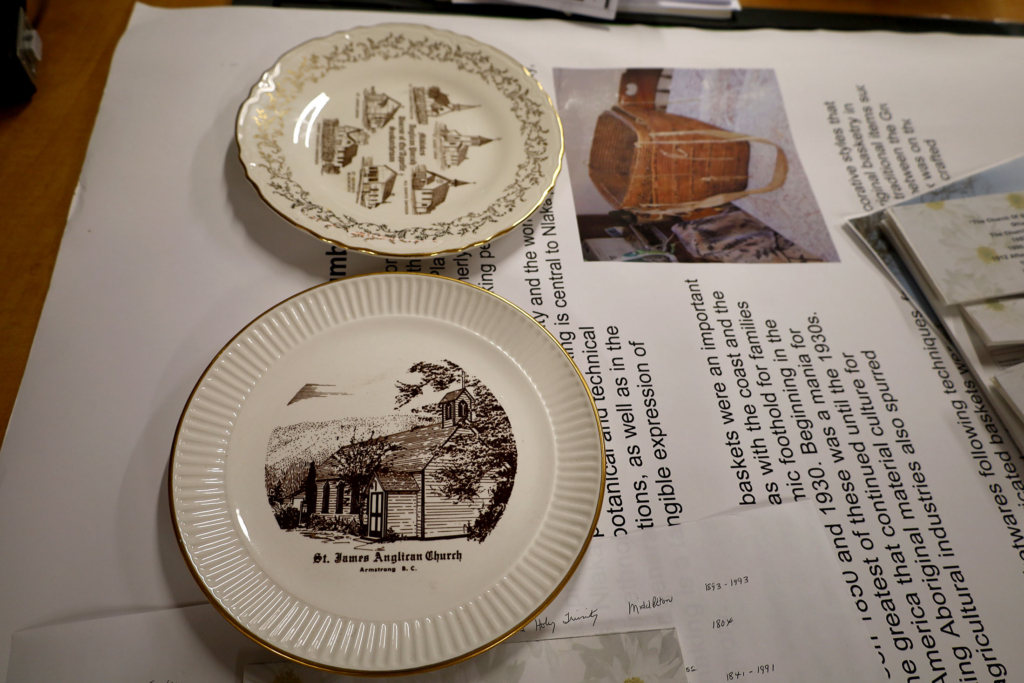

JAYME: Four major cultural collections were lost in the fire: the Lytton Chinese History Museum, the Lytton Museum and Archives, a collection of Nlaka’pamux baskets, and a collection of Anglican commemorative plates, though countless collections of personal significance also perished.

LORNA: Yeah, so the hole in the ground we see here is the remains of the museum. And it would've been almost right at the, at the front of this level ground. And then the back of the building would've been kind of where you see the edge of the concrete in the bottom about there. And then the rest was dirt before.

JAYME: Lorna Fandrich founded the Lytton Chinese History Museum in 2017 to tell the stories of Chinese settlers in Lytton and the surrounding areas. It was built at the site of a former Joss House just down the embankment from the railway tracks. A few blocks away across town, the Lytton Museum and Archives resided in an old railway workers house and was the municipal museum, collecting objects related to the Lytton area. These ranged from ancient fossils to artifacts evidencing histories of settlement. It is the second major collection lost in the fire.

RICHARD: we're walking right beside the museum right now, was a really nice little railway worker’s house. About 25 feet square, roughly, maybe 30 feet square, and main floor and a basement on half of it. That hole is where the half basement was, and over there there was the crawl space there.

JAYME: Richard Forrest spent decades stewarding the collection and is an expert on the history of the town. For Richard, as for many community members, Lytton’s archives didn’t only exist in the footprints of museums.

RICHARD: This is an old, um, drill that they used to use to drill the holes in track. These down here are hay tongs. All this paved out stuff here was called Caboose Park because we had a beautiful 1940s wooden caboose here.

JAYME: Lytton First Nation’s collection of Nlaka’pamux baskets also lived in many places, from personal homes to public institutions. It was the third major collection taken by the fire. John Haugen is an Nlaka’pamux knowledge keeper and lost his mother’s collection of baskets.

JOHN: Other than the Looking First Nation, the collection outside of that that was quite large was my mother and my own personal collection. People would bring my mother or I baskets saying that their family no longer wanted these and they wanted us to have them. So those were the two huge collections in town. And then from the homes that got burnt down, there were probably about 20 homeowners that had varying collections within their own private homes.

JAYME: When John was telling me about the baskets, he also mentioned a collection of Anglican Plates. They’re a type of commemorative dish made by churches to celebrate special events or milestones. The town’s Anglican Church started collecting them to celebrate its 90th birthday in 2012. The plates were the fourth major collection destroyed by the fire and, according to John, the church had a lot.

JOHN: And we knew we had a few of these Anglican plates around. So, we had suggested why don't we try to get 90 of these plates and just put them on display. And so, people brought out from their own home collections and some people had looked in thrift stores and we had gotten really close andmany people thought we had the largest Anglican plate flexion in Canada here in BC Lytton.

JAYME: Lytton is a place where its history is uncommonly present. Piles of rubble produced by mining still mark the landscape. Acacia trees once used to make wagon wheels during the gold rush flourish on the hillsides. Trains frequently pass on the railroad tracks above and below the town.

TRAIN AUDIO

JAYME: Many Chinese communities who emigrated to Canada worked on the railway. Lorna showed me a small green jar that had survived the fire. It is a so-called “ginger jar,” used by Chinese settlers to store pickles and food. The jar is cool to the touch, about four inches high and hexagonal in shape, collaring in from the shoulder to a smooth circular rim. The glaze is a dark jade green, though exposure to heat and ash during the fire has caused the glaze to crackle and change colour, turning it a deep rust in patches. Decorative images, faintly discernible through the layer of glaze, have been pressed into the sides of the jar, each encased in a rectangular frame. Lorna tells me the jar is missing its cork lid, which burned during the fire.

TRAIN AUDIO

JAYME: In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Canadian Government built three railways through Lytton. First there was the Canadian Pacific Railway in the late 1800s. It was built to establish coast to coast nationhood in Canada. It was followed by the Canadian National Railway and the Pacific Great Eastern in the early 1900s. Together, they connected towns, encouraged trade, and brought crowds of workers to Lytton. By connecting settler outposts in the province, the Canadian Government used infrastructure to bring First Nations homelands under the nation’s control.

TRAIN AUDIO

JAYME: So let’s slow down for a second. Land is important to the telling of history and its worth being clear about what that means. Most of British Columbia sits on unceded First Nations land—about 95 percent. The Village of Lytton is part of that ninety-five percent. What that means is that across most of the province, treaties were not signed between First Nations and settler governments. Instead, in much of British Columbia, land was just taken from the First Nations people living there, who were told to live on much smaller reserves. This happened through a labyrinthine series of governmental policy and acts including the federal 1876 Indian Act, the 1879 Dominion Lands Act and the Consolidated Railway Act passed in the same year, as well as the provincial 1916 McKenna McBride Royal Commission, among countless others. Embedded in each are provisions of land for the passage and financing of the railway.

TRAIN AUDIO

MARIO SORIANO:

An Act respecting the Canadian Pacific Railway. (44 Victoria. chapter. 1—1881) Schedule—Contract, dated 21st October, 1880, Schedule A, referred to in the foregoing Contract. Section 12. The Government shall extinguish the Indian title affecting the lands herein appropriated, and to be hereafter granted in aid of the railway.

JAYME: To build the railway, railway companies needed money and they needed land. The government facilitated this by simply taking land from landholders and giving it to the railway company, who could then build on it and sell any extra to raise funds. These “railway belts” often eroded the already small portions of reserve land that were allocated to First Nations communities.

JAYME: The Railway Belt extended approximately 20 miles (32 km) on either side of the railway.

JAYME: In 1914, Billy Sigh of nearby Boston Bar testified to the McKenna McBride Commission. In a transcript of that testimony, he explains:

MARIO SORIANO:

“I have had some trouble with the C.P.R. They want to take my land—that is, the land I have been living on for some years. They told me I would have to leave there because it belonged to them. The C.P.R. has moved their fence right up to my house, and they have taken in the principal dwelling part. I am talking about [reserve] No. 2. and they say I will have to move away from there.”

TRAIN AUDIO

JAYME: When the train runs through the town, it’s hard to ignore. It hisses and screams and, if you stand close enough, the ground shakes. It's the feeling of friction: metal on metal. Today the train drowns out the sound of cars on the highway farther up the slope. The highways now follow a similar route along the river.

FADE TRAIN AUDIO

JAYME: When you drive into Lytton, you pass a sign welcoming you to “Canada’s Hotspot” before driving under a CN Rail overpass. Lytton does record the highest temperatures in Canada, and this has to do with its geography. Lytton sits deep inside the Fraser Canyon, which acts like an oven: as the mountainsides heat in the sun, they trap hot air by the valley floor. Sagebrush, Douglas fir and pine trees are fuel for wildfires.

British Columbia faces a fire season every summer. The risk is so high that the whole province is under a seasonal campfire ban. But some years are worse than others, and several factors determine how intense a fire season will be. And one of them is the heat. In 2021, the entire Pacific Northwest experienced a record-breaking heat wave.

Community members remembered the heat that summer.

LORNA: The two factors that were the big deal in this fire obviously were the extreme heat, but also Lytton is always windy or almost always.

JAYME: That’s Lorna, who started the Chinese History Museum.

LORNA: The day of the fire, I was out just keeping my yard spiffy. When I went home, I said to Bernie, it's the weirdest thing because the, even the acacia trees don't like this heat. Their leaves were crumbling, like a dried herb.

JAYME: On June 30th, the day after Lytton reached 49.6 degrees Celsius—that’s 121 in Fahrenheit—the conditions are just right for fire. As Mike Flannigan, the research chair for predictive services, emergency management, and fire science at nearby Thompson Rivers University explains, it was hot, and this created the perfect conditions for wildfire.

MIKE: The previous all-time record high temperature for Canada prior to the 2021 episode was 45 degrees Celsius. Lytton broke that on the 27th, broke it again on the 28th, broke it again on the 29th, 49.6 degrees Celsius.

The wind is blowing strong. The fields are crispy. You walk them and you go crunch, crunch, crunch.

Then you get little burning embers. It's almost like a leapfrog process. And then it starts building a column. And it just moves in the direction of the wind most intensely and most rapidly.

And ire is opportunistic, it's probing, it's searching for something to burn. If it finds something, away we go.

JAYME: Once there was ignition, the fire burned fast, reaching town in under 20 minutes.

RICHARD: One of the worst things about the fire was it happened so darn quickly.

RICHARD: I came into town to pick my wife up at about 10 to 5.

JAYME: This is Richard from the Lytton Museum and Archives.

RICHARD: And there was smoke at that end of town. And I drove down to have a look and see what was going on. And the fire came over the edge of the road and jumped across the road where the railway tracks are. I went up and I turned around and came back and by that time, a friend of mine’s house was burning at the end of main street, right there, couple of doors from Lorna’s museum.

LORNA: My daughter phoned me and said, mom, there's a fire in town. And then all my husband and I could think of was, the whole town is going, we knew it already. I didn't think about my two sons' houses, I didn't think about the museum, I didn't think about her store. We just went and got our daughter, got her to get her staff outta town and, and then we left.

It was so quick. The whole town burned in 26 minutes.

JAYME: Residents chose between three evacuation routes from Lytton: northwest to Lillooet, northeast to Kamloops, or southeast to Merritt. Most people stayed with friends and family. The fire kept burning for days.

PATRICK: I checked, oh shit, I've lost my house. Holy shit, I've lost my hometown. We lost our data, we lost our survey pins, we lost everybody.

JAYME: This is Patrick Michell again.

PATRICK: It wasn't just a portion of the town, it wasn't just a house. An entire town that is a catastrophic loss that had never happened in Canada before.

JAYME: The Lytton fire was unique in its total destruction of the community: after the fire, there was nothing to return to, nowhere for residents to gather. But there are many ways to measure the scale of a fire. That same summer, the Sparks Lake Fire near Kamloops caused a kind of fire-thunderstorm—called a pyrocumulonimbus—that generated thousands of lightning strikes. In 2016, the Fort McMurray Fire in Alberta forced 88,000 people to evacuate. And in 2003, the Okanagan Mountain Park Fire consumed 239 homes in Kelowna and threatened the town, forcing the evacuation of 27,000 residents.

I grew up in Kelowna, which is just a couple hours from Lytton, and spent about three weeks evacuated from my home that summer. I had many friends that lost their houses, their family photographs, all their clothing. I remember checking the news daily to see if my family’s home had been taken; and I remember the night the wind changed, blowing the fire from within a few hundred feet of our home back into the mountains.

And since 2003, wildfire seasons are getting worse. Since the 1970s, the area burned in Canada has doubled, and in the western United States, it's quadrupled. Just three years prior in 2018, the most destructive fire in California's history leveled the town of Paradise, killing 85 people. This past summer in 2023, a wildfire destroyed the historic Hawaiian town of Lahaina, killing 98 people.

MEDIA CLIPS: Dozens of wildfires continue to torch the western US and Canada. // The snake river complex is the highest priority wildfire. // Cornville fire. // California, the Caldor Fire // Telegraph, Mezcal, and Slate Fires // the Hoover Ridge fire // thousands of evacuees in limbo // whipping winds will again fan ferocious flames today // experts are having to find new ways to convey just how extreme the situation is.

I asked Mike Flannigan, the fire expert, about the relationship between climate change and wildfire. He says that there are three ways that climate change impacts fire season.

MIKE: The warmer it gets, the longer the fire season is. Fire season starts earlier, ends later.

Second, the warmer it is, the more lightning we expect. All things being equal, more lightning means more fire. 50% of the fires in Canada are started by lightning, but they're responsible for most of the area burned. Third reason is probably the most complicated, but probably the most important. As the atmosphere warms, the ability of the atmosphere to suck moisture out of those dead fuels on the forest floor increases almost exponentially. The drier the fuel, the easier it is for a fire to start, the easier it is for a fire to spread, and it means more fuel is available to burn.

JAYME: When I talked to Mike, in the summer of 2023, Canada was experiencing its worst wildfire season on record.

MEDIA CLIPS: Tens of millions of people have been warned about potentially dangerous air quality as intense wildfires burn across Canada // Today, the sun rose over the Northeast shrouded in smoke. Haze covering Manhattan’s skyline and bridges and the Washington Monument in D.C. // Forest fires are a reoccurring nightmare // and with the heat rising and no rain in the foreseeable future, conditions will remain ripe for more fires.

While the Donnie Creek Fire burned in northern British Columbia, the eastern provinces like Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Ontario also faced record-breaking fires. The fires were so bad that smoke was changing the air quality across the continent.

MIKE: I've done research in climate change and fire for over 30 years. And, you know, some of the models that I produce suggest the west would be where we see the signal first, and then kind of mid-century we'd see it in eastern Canada. Perhaps we're seeing it a lot earlier than mid-century. Perhaps this is the start of what's coming.”

JAYME: On the global scale, climate change is driving more intense and more frequent wildfires. But to Lytton residents, the fire isn’t exactly a climate change story. Residents point out that they live in a fire ecosystem. The Fraser Canyon has always been dry and hot, and it has always burned. But many residents do blame what they believe to be the source of the spark.

On the day of the fire, multiple people saw sparks beneath a CN Railway train as it headed toward Lytton. The first report of the fire happened twenty minutes after the train passed through town.

PATRICK: The first witness was Chief Jordan Spinx from the Kanaka Bar Indian Band. He saw the fire, he was on 911, he's running, and before he got to Lytton, the town was on fire. A dynamite fuse.

JAYME: An investigation by the Transportation and Safety Board of Canada found no evidence that the train started the fire. Still, the Village of Lytton is suing the national railways for running during the heat wave despite the extreme fire risk. The case will go before the BC Supreme Court.

This disjunction between the official and the community account of the fire can feel like another scene in the long history of the railroad where governments and companies neglect the railway’s effect on the local communities who live alongside its tracks.

Even if the fire wasn’t started by the train, the railway company is responsible for caring for weeds and debris along the tracks. Community members like Richard and Patrick point out that the condition of this property is a real risk point for fire.

RICHARD: The railways are terrible. They're just terrible. It used to be that they would, they would take and they would just spray weed killer all the way along. And then the environmental people said, no, no, you can't do that. So the weeds grew up and then there's sparks because it's machinery, heavy machinery, eh?

And there's sparks all over the place and you end up with fires being caused.

PATRICK: Did a spark from that train cause that fire? We can't prove it. Was the ember so hot that just a piece of soot could have fallen off the diesel locomotive and started that fire? It’s a possibility. Lytton burned down, but we don't know the cause yet. Do we need to? It doesn't matter how the goddamn fire started, what matter is it started on your property and burnt my house.

JAYME: What caused the fire isn’t the topic of this story. But as I spoke to people in the community, I came to understand that how one defines what caused the fire has a huge role in how recovery happens. If the train caused the fire, the railroad company might be liable for the damage. If climate change caused the fire, as the government said, then the solution would be to build back “net zero,” which has massively delayed rebuilding. If the cause was simply because it is a fire ecosystem and the community did not fully implement so-called “fire smart” practices, then “net zero” is not necessary, only an improvement of fire-aware planning and maintenance. Stories matter: they have an important role in how communities recover—not just their physical homes, but their local cultures and connections too.

MUSICAL BRIDGE

JAYME: In 2021, Lytton lost four major collections in less than an hour. The plates, the baskets, the Lytton Museum and archive, the Chinese History Museum. Almost nothing remains. Even the town’s bylaws were burned, as was the backup—which was stored in the basement of the Lytton Museum and Archives—and they’ve needed to be rewritten from scratch. These losses are in many ways irrevocable—many of the objects and documents simply can’t be replaced.

Two years after the fire, stewards are still grappling with how to rebuild. Their commitments to their collections show that archives are not inert repositories of documents and artifacts but community collections that connect generations and carry histories forward. As they move forward, stewards are facing big questions. How can these archives and museums continue when most of their objects are gone? What gives archives like the ones Lytton lost meaning to the people who steward them and to the communities around them?

MUSICAL BRIDGE

Part 5

We tend to think of archives and museums as separate from regular daily life—they are cleaner than other spaces, more regulated, they are climate-controlled, and have extensive mechanisms for protecting objects from security guards to glass casements. However, archives and museums are still ecological spaces: a spider might build a web in a corner, dust might gather, a pipe might burst and mold and mildew could grow in a wall. As much as they might try to be outside of ecological processes, they are very much embedded in them, and as climate change leads to more frequent extreme weather events, the risk of a flood, a fire, or some other ecological crisis invading the pristine space of an archive is growing. We’re seeing examples unfold in real time, and across large and small institutions. In 2017, melting permafrost caused a flood at the Svalbard Global Seed Vault and imperiled seed samples. In 2018, a fire at the National Museum of Brazil resulted in Alexandria-level losses of cultural material. In 2020, a fire at the Museum of Chinese in America in New York City led to fire losses in the display collection and extensive water damage in the archives.

In Lytton, it wasn’t just part of a collection that was lost: it was everything from the four main collections—not to mention the personal collections that live in trunks and on bookshelves in peoples’ houses. Consider the scale of the loss:... not only were these collections lost, but everything down to the town’s bylaws, tax documents, and financial records were gone. The fire incinerated the material that would provide the foundation for recovery.

As a place-based, research-driven story series, Archival Ecologies will look at how communities move forward from events like the 2021 fire. This first season will tell the stories of Lytton’s cultural institutions through the voices of the people stewarding its four main collections, and through the places and histories surrounding them. You can expect a deep dive into objects and their histories, an introduction to the multicultural geographies of the Fraser Canyon, close-up looks at each collection and the people stewarding them, interviews with archive and preservation experts, and a range of perspectives on what collections mean and what recovery from loss looks like.

As stewards and conservators grapple with the loss of collections, they talk about what was lost, describe the many challenges of recovery, and consider the broader implications of how to protect and carry forward the stories that archives and objects hold in the face of continued risk. The new collections stewards imagine sometimes look quite different than the ones they had—instead of a collection, for example, perhaps a community center for teaching cultural practices, instead of an object, digital repositories of photographs, documents, and 3-D scanned objects. In these differences stewards show a variety of approaches to what it might look like to recover from an event like the Lytton fire. These differences also signal important cultural transformations that are becoming more pervasive as extreme weather events become more frequent and widespread.

As researchers, we’re really interested in how climate change is changing our relationship to cultural material, to the stories we tell about who we are. If archives and collections let us tell histories to better know ourselves in the present, and to imagine where we might go, what happens when those objects are no longer there? What kinds of stories do we tell and how do we tell them? How do we imagine the futures we might move into?

In the coming episodes we’ll dive into the archival ecologies of the Lytton area and its cultural collections. Stay tuned for more on how our cultures are changing with the weather.

Archival Ecologies is created and hosted by Jayme Collins, and is a production of Blue Lab at Princeton University. For their support and expertise, we also thank, at Princeton, the High Meadows Environmental Institute, the Humanities Council, and the Office of the Dean of Research, as well as Kouvenda Media. This project has also received invaluable research support from Jamie Rodriguez, Kavya Kamath, and Molly Taylor. Voiceover by Mario Soriano. Music by Hamilton Poe.

Two years after a devastating 2021 wildfire burned through much of their village center, community members gather in Lytton, British Columbia for a prayer walk. Big questions inspire and inflect the event: How can the community rebuild? And what will the new community look like? Lytton community members weigh in on preserving their multicultural histories and recovering community identity when the artifacts and cultural collections that represented them are gone.

Pauline and Ernie Michell, Pastoral Elders from Nlaka’pamux nation, at a multi-faith rebuilding blessing event on the second anniversary of the Lytton Fire (June 30, 2023). Photo by Molly Taylor.

A sign welcoming drivers to Lytton, Canada’s “hotspot” in the Fraser Canyon region of British Columbia. Photo by Molly Taylor.

Community members walk along Main Street through Lytton, British Columbia on June 30, 2023, two years to the day after a devastating wildfire burned down much of the town. Photo by Molly Taylor.

A “ginger jar” from Lorna’s collection that survived the fire in the Lytton Chinese History Museum. The fire has turned the jade-green glaze a rust red in patches. The jar is missing its cork lid, which burned during the fire. Photo by Jayme Collins.

A CN Rail train passing above the site of Lytton’s Chinese History Museum, still fenced off. Photo by Jamie Rodriguez

Episode 2: Salvage

Archival Ecologies Episode 2: “Salvage”

Full Trascript

Lorna

We came by her and there was a little, um, towel put out, and then there were like 10 little half broken ornaments on there that they were spraying. It was something to decontaminate them and that's what they were finding in her to remember her whole house by.

Heidi

Because it was three months later, the entire site was covered in sunflowers that had seeded from bird feeders, or we don't know where they came from but they were growing in almost every property possible. So there was this strange, beautiful thing happening amongst these ruins.

Jayme

Welcome back to Archival Ecologies, a story series about the intersections between archives and cultural collections and the environments where they reside. This season, we’re traveling to the historic town and reserves of Lytton, a small town in the Fraser Canyon region of British Columbia that burned down in a 2021 wildfire. Archival Ecologies is led and hosted by me, Jayme Collins, and is a production of Blue Lab at Princeton University.

[instrumental interlude]

Archival Footage: News Broadcasters

“Lorna’s museum, along with the village office—nothing stood a chance.”

“The collection was second only to the Royal BC museum and it was one of the most important ones in North America.”

Jayme

In this episode, we’ll follow just one of the many stories of salvage and recovery that have defined the area’s archival ecologies since the fire—the story of the Lytton Chinese History Museum and its founding director, Lorna Fandrich.

Archival Footage: News Broadcasters

“Lorna Fandrich is trying to rebuild the Lytton Chinese History Museum and, like many other businesses, is hitting one roadblock after roadblock.”

“The process has been heartbreaking but also rewarding for Lorna, who's determined to rebuild.”

Jayme

We start this episode’s story in a small patch of grass next to a parking lot near the Stein Valley Nlakapamux School, the community based independent school on the Lytton First Nation reserve just 5 minutes north of the Lytton town center. A music festival called Two Rivers Remix is under way in a field behind the school on a plateau elevated above the river. The grass has been mowed. It’s green still, but dry and spiky to the touch from the threat of the desert’s heat, even now in early summer. It’s late June and the Fraser Canyon typically won’t reach its hottest for a few more weeks. And yet, music festival volunteers circulate with spray wands, dousing the grass in water to prevent the outbreak of fire. There are electrical wires criss-crossing the field to power the musical equipment.

There isn’t anything remarkable about this particular patch of grass, and yet with each step, grasshoppers erupt from the ground around me, otherwise invisible in the small shade available between the blades of grass. With each step a new wave crests away from me: this small patch of earth is brimming with grasshoppers.

[grasshopper sound]

Grasshoppers have always lived in this ecosystem, although they haven’t always been welcome. Embedded in the grasshoppers is a story about contamination and about the residues of history that, though unseen, live in the soil and continue to shape how humans, animals, and insects make life here.

[grasshopper sound]

In the 19th century, across the arid grassy regions of the interior of British Columbia that includes Lytton, settlers established ranches, grazing cattle across the Bunchgrass plateaus that border the region’s rivers. During this time, grasshopper irruptions rarely posed a problem. By the late 19th century however, overgrazing and other land management practices that attended colonization gave rise to grasshopper swarms that damaged grasslands and negatively impacted cattle grazing. As cattle herds grew, grass everywhere became smaller, younger, and more tender, providing good food for the grasshoppers who preferred the fresh sprouts. A feedback loop: Unregulated grazing transformed the grassland habitat into prime grasshopper habitat, which in turn threatened the cattle industry.

Focused on ranchers’ livelihoods, the provincial government chose not to regulate grazing activity and instead launched a pesticide campaign that applied chemical agents—arsenic in particular—to large swathes of land in an attempt to control the grasshopper population. While the results are sparsely recorded in the historical record, there is evidence that the poison did not only kill grasshoppers. Chickens and some cattle were also killed while the wider ecological effects on wildlife and on waterways remain unknown.

In this period, the government also lobbied First Nations residents to treat their land with the same chemicals, perhaps in a place like the patch of grass I stood in last summer. In one recorded instance from the 19th century, the poison killed cattle, chickens, and made several children ill on one reserve. That community then refused to place any more on their land. But that isn’t to say the arsenic wasn’t all around them, didn’t leach into the water, foods, wildlife, and soils.

The soil stores the residues of these chemicals, just as it stores other fragments of history. Surviving in this landscape is to survive contamination and to navigate the histories embedded in the soil. The story of surviving the fire is no different. After the fire, the soil beneath the village of Lytton was contaminated by incinerated building materials; at the same time, it became an archaeological site. Patches of earth that buildings had covered for a hundred years were revealed, making it possible to excavate for artifacts, especially from the First Nations village that was there before it was Lytton.

Patrick

The mayor sits down here and he does something different. He talks to the province, says, look, I'm a little concerned ‘cause many of these buildings here were built in the early 1900s, 1920s, the ones that weren't lost to various fires. So can we test the soil? The soil tests come back. It's 584 pages long.

There's immediate risk to health and safety in the water, in the air, and in the soil.

Jayme

This is Patrick Michel, retired chief of the Kanaka Bar Indian Band and lifelong Lytton resident who lost his house in the fire. In the summer of 2023, two years after the fire, the town center is still a mess of dry dirt, weeds, concrete, plastic, rebar, styrofoam, and other building material pockmarked by huge holes—evidence of the effort to ascertain and remove contaminants that the fire released into the soil. This landscape is a visceral reminder of the slow pace of recovery.

Richard

Um, what would be the right word? Discouraging, yeah.

They had to take off dirt. And then when they took the dirt off, they decided that, oh yes, but it's a historical site, so we have to do archaeological.

Jayme

Richard Forrest is showing us around the site of the Lytton Museum and Archives, which he founded and continues to steward. As Richard describes, central to the recovery process has been de-contamination, which has involved arduous processes of repeatedly testing and removing soil. In British Columbia, given provincial regulations about digging in sensitive cultural areas where there may be First Nations archaeological material, this work has needed to be done in collaboration with archaeologists. The ground here is more than biological matter—it’s also a historical archive of life, from pre-colonial settlement patterns through to the industrial and chemical infrastructures of contemporary life.

Patrick

The problem is the archeologists couldn't come until the contamination was done, but the contamination couldn't come in until the archeologist cleared the land.

30 yards from us they found human remains.

Richard

So between the two of them, it's been two years.

Jayme

In the immediate aftermath of the fire, concerns about contamination forestalled any opportunities for the recovery of cultural and community collections in the burn zone.

Kasey

We couldn't gain access to the site for a full three months afterwards.

Jayme

This is Kasey Lee, an object conservator and one of the founding members of the British Columbia Heritage Emergency Response Network. This province-wide organization trains conservators and community members in the protection and recovery of heritage materials during emergency situations and organizes response teams. Kasey was on the ground in Lytton during a salvage operation for cultural material that survived the fire.

Kasey

It was declared a contaminated site, um, they had, you know, the products of combustion and Lord knows what else, asbestos and... mold.

It was evident by October that there were some cultural sites that could possibly be salvaged. And the sooner the better. Winter was coming and things were exposed.

Jayme

For three months after the late June fire, artifacts and other significant materials sat out in the weather, exposed to the elements—including a cumulative 14 centimeters of rainfall—to contaminants, to nesting and burrowing animals, and to other curious interlopers. To survive both the fire and this period of exposure, any one object needed to be very durable—metals and ceramics, say, instead of paper or plant material—and was probably buried in protective layers of ash.

But by fall, time was of the essence.

Winter was coming fast and the site was still under quarantine: not even residents had been allowed back to see what remained of their homes. Then, one month after the team of conservators finally gained access to the site, atmospheric rivers drenched the province, causing mudslides in the burned areas that devastated the highway system in the province. Two years later, that too was still being rebuilt.

Across three weekend-long visits, the conservators worked across all the heritage sites in Lytton, but they were particularly successful in salvaging material at the Lytton Chinese History Museum, in part because of the nature of the collection: ceramics are designed to survive fire.

Lorna

I just knew that if it wasn't pottery, I'm not gonna find it. You know, I just knew it was, yeah, it was past that already.

I've had many people ask me why I'm still rebuilding. There may not be a community, there may not be tourists. Uh, two reasons. I still wanna tell the Chinese story. And because, um, I don't wanna be one of the businesses that bails on the town either. So whatever small contribution I can make, I would like to go ahead.

Jayme

Opened in 2017 on the site of a former Joss House or Chinese temple building in central Lytton, the Lytton Chinese History Museum aims to carry forward the histories and experiences of Chinese settlers and migrant workers in the area.

Lorna

And so 2015 it became a BC Chinese historical site and then it's also on a Canadian registry. And with that then I thought, okay, I have credibility with the Chinese community now.

And so then I just went ahead and decided to build it in 2016 and we opened in 2017. And then of course, as you know, it lasted from 2017 till 2021 when the fire occurred and we lost everything. There were 1600 pieces there

Jayme

In one sense, the museum has always been a project of recovery—recovery of a site whose significance to the town as a Joss House had been forgotten, recovery of an undertold history of objects and the people and lives for whom they were meaningful.

Lorna

So for the original museum in 2016, I only had 200 artifacts. Some from here, some from, actually, Kumsheen because there was a railway camp here in 1883. And so I had very little and then as I started putting up the building, a man, Al Dreyer from Lillooet, came and asked me if I would like to buy his collection. That was just over 800 pieces and he had collected them over the years from Lillooet, Lytton, and Ashcroft.

Jayme

Much of Lorna’s collection came from local sites, gathered by residents from the landscape: objects sometimes on old trash sites or just next to the river where people would walk. Objects lay out in the weather for decades, becoming embedded in the landscape to persist as history.

Lorna

He would go to the common sites. So for example, in Lytton, a lot of the pieces that he collected were just over the bank from what is the reserve end of the town. And that's because at that time, everybody just threw all of their garbage over the bank, towards the river. So that was the beginning.

So upstairs we just sort of began with talking about people coming for the gold rush. Artifacts there were partly from here, um, things like mule shoes or gold pan or things that we found on this site actually.

And then, um, about 12 miles up the Fraser, there was a Chinese mining camp there. It's on indigenous land. And so Bill Paul, um, lives on that land. And so he brought me a lot of, a lot of pieces more to do with mining or, or household things, you know, that had been out beside the river for years. Very rusted.

Jayme

Lorna also gathered objects from Chinese settlers who had since moved away from the Lytton area and who chose to donate their objects to the museum to tell the history of their family in this place.

Lorna

And the ones I feel the most sad about are the things I got from the Chung family that were here.

So I’ve got pieces of their mom's diary, I think it was their wedding skirt, and lots of documents about, they leased land from other people here to grow vegetables in the 1920s. And those are the things, uh, I'm really sorry I lost. I have photos of them luckily, but, uh, I did lose those. For the Chong family, that was tough, yeah.

Jayme

In the wake of the wildfire, Lorna has been determined to recover these histories for a second time by rebuilding the museum.

Lorna

It's a difficult decision when you're just told, okay, you're leaving now, and what do you take, you know, we have the bags packed for the insurance, your personal items, but deciding what to take. So if I'd gone in the museum, I know I wouldn't have thought of a thing, but it was too late anyway. It was way too late.

Just gone, you know? Oh, I mean, what can you say? It's gone

Jayme

Intermixed with Lorna’s commitment to rebuilding is this profound sense of loss. While much of the museum’s collection has a digital record, many of the pieces are irreplaceable. Rebuilding therefore raises a number of questions: how do you create a local history museum with only a few surviving objects, themselves significantly altered by the fire? What stories do these remaining objects tell? Can newly acquired objects—some of which may come from different areas—convey the same local histories?

For Lorna, the power of objects inheres in the stories people attach to them, and in the intergenerational memories and family histories that stir in people when they encounter a familiar item.

Lorna

Once two ladies came, they were from Edmonton. There’s a 60 year old and she had brought along her aunt and aunt’s friend and they were like 90 and they came in and they went into the room where I have all the medicine bottles and they started talking really excitedly.

And they just started laughing and talking to me and saying, oh yeah, this medicine here, I mean, they're 90, right? My mom used to force us to take this all the time and it tastes terrible. They couldn't believe there would still be a bottle around of this terrible stuff, you know? So those are the things that were fun for me when people came in and it just brought back this memory of their early time, which is yeah, pretty good.

I tried to convince one of those ladies to just stay, to tell stories all summer, but it didn't work.

History of Gold rush

Jayme

The history of Chinese settlers in central British Columbia is shaped by absence—of

documentation, of artifacts, and of first-hand accounts. According to the predominant narratives, that history begins when the gold rush reaches the province in spring 1858, at which point British Columbia is colloquially known as “Gold Mountain.”

March 22, 1858, Puget Sound Herald

Newspaper voiceover

“LATE AND IMPORTANT FROM VICTORIA, VANCOUVER ISLAND

GOLD DISCOVERY CONFIRMED!

Rich gold fields found on Fraser’s and Thompson’s rivers

By the arrival at this port yesterday of the schooner Wild Pigeon, Captain Jones, we have been put in possession of late and highly interesting intelligence from the goldfields of the Shuswap country. Captain Jones reports that the excitement relative to the gold fields lately discovered on Fraser’s and Thompson’s rivers is very great.”

Jayme

Piles of rubble from this period that stand taller than a person can still be seen along the rivers in the region, and even in the middle of towns like nearby Lillooet. They are reminders of how foundational gold rush history is to life here. And mining continues to shape the region’s ecology—to this day, people can still stake claims for so-called “placer mines,” which involve digging up gravel adjacent to streams (either by hand or with excavation equipment) to find the gold flakes within it. It is remarkably easy and cheap to stake these claims. There’s an online registration and a nominal fee of a couple of hundred dollars and these claims can be made within private property and on First Nations reserve land. These informal mining operations never undergo environmental assessment despite there being evidence that they have a negative effect on salmon stock and on the broader river ecology.

The Fraser Canyon gold rush would last less than 10 years, petering out by the mid 1860s, but it utterly transformed life in the area. The Fraser Canyon War broke out in June 1858 between predominantly white miners staking claims to land and Nlaka’pamux people defending their territory. The economic boom of the mining industry made the land very valuable to both British and American interests, leading to Britain claiming British Columbia as a colony in August 1858, mere months after the discovery of gold. It became a colony that would go on to join Canadian Confederation in 1871. It was British Columbia joining Confederation that led to the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railroad.

During this time, many Chinese immigrants arrived in search of a fortune in gold or in search of steady—if dangerous—work on the railroad. After the railroad’s completion in 1885, Chinese workers were left stranded. A series of laws passed by the government between 1875 and 1923, including the notorious Chinese Exclusion Act, disenfranchised Chinese immigrants and their descendants (depriving them of the right to vote) and limited further immigration to the province. The lack of readily available employment in white society led to vibrant communities of small businesses in Chinese enclaves and Chinatowns.

There is one surviving first-hand account of Chinese life in central British Columbia from this period in the Diary of Dukesang Wong, a man who emigrated from China in search of prosperity

and worked in harsh conditions on the Canadian Pacific Railway in the late 1800s. After the railway’s completion, Wong would go on to become a tailor, raising 8 children in the province with his wife.

For many years, Wong’s diary wasn’t known to historians, nor was it collected in a museum. It survived in the family after his death and was translated into English in the 1960s by his granddaughter Wanda Joy Hoe as a school project. The original diary burned in a fire just a few years later, but the translation survived, tucked away in a desk for years until a writer named David McIlwraithe learned of its existence when he encountered a fragment in a small museum in the Fraser Canyon. He reached out to the granddaughter and facilitated publication.

While only pieces of Dukesang Wong’s diary survived the years, it is an invaluable first-hand account of the harsh labor conditions and day-to-day lives of Chinese railroad workers

in British Columbia. It is a crucial document of illness, starvation, dangerous work, and racism. Today, the English translation can be found in bookstores and libraries all over North America.

Reader for Dukesang Wang’s Diary

“My soul cries out. I wish I had never experienced such bad days as those in which we now live. Many of our people have been so very ill for such a long time, and there has been no medicine nor good food to give them…. The white doctor has told us the illnesses come from lack of fresh food, but we cannot grow any fresh food, as all of us, including the white people, are moving constantly with the work we have to do.” (p. 59)

Jayme

Many such firsthand histories like Wong’s diary live tossed over an embankment in a junk pile or tucked away in a drawer. Nor do all such histories need to be public. But Lorna’s museum was a place that brought disparate documents and objects together—a project of salvage and recovery that held space for the personal histories that have shaped life in this landscape.

Lorna

To me, having the physical objects there instead of a photo, for example, has more value in my mind. But at the same time, if you didn't have those, at least have a digital collection, you can still tell the story. That's what we're about, right. We're not about having, you know, 25 pots or 10 old cars we're about what, what happened with the old car?

Jayme

Lorna’s approach to recovery from the fire is shaped by a similar spirit of salvage and recovery.

[music]

Lorna

This is where the cement walls were still here, right?

Jayme

Standing at the site of her museum, Lorna remembers what she saw her first time back, 3 months after the fire.

Lorna

So everything had. Fallen down and had burned. And so there was about 14 inches of

ash with just a bit of metal which was like the stove, the fridge, uh, ducting. And, and a few of the display cases were still showing, but right here is where some of them were melted to the cement with the melted glass, and they were standing up in the air like this.

Because the glass had hardened before they actually fell.

Jayme

In the immediate aftermath of the fire, local stewards reached out to BC Heritage Emergency Response Network. I talked to two conservators—Kasey and Heidi—who were on the ground during the salvage mission in Lytton.

Heidi

I'm Heidi Swierenga, and we're here at the Museum of Anthropology at UBC, where I am the Senior Conservator and Head of the Collections Care Management and Access Program. I'm on the steering group of the BC HERN, the British Columbia Heritage Emergency Response Network.

A few local conservators kind of stepped back from those incidences and said, well, surely, there must be some organized response to a heritage after an emergency. And so we started looking across Canada to see if there were other, any other processes out there, and we quickly found that no, there was nothing out there that already existed within the country for emergency response of collections after an emergency or a disaster. Heritage seemed to be this missing piece of the puzzle, both for response and recovery.

We were contacted at the outset by John Hogan and Laura Fandrich just by email saying, This has happened. We don't know what's going on. Hoping you can help in the future.

Jayme

It would be three months before anything happened.

Heidi

We were contacted by Team Rubicon Canada, who turned out was one of the first NGOs who was given the permitting to gain access to the site, which, which community members and family members still hadn't been able to get back.

Kasey

I don't know that much about Rubicon, but they enabled us to gain access to the site, and provided us with the advanced training in personal protective equipment that we needed, got insurance in place, made us these what they call spontaneous volunteers.

Heidi

We were at the Lytton Museum and Archives. And then we were working with John Hogan on a couple locations, uh, within the community. And most significantly, it was the Elgin, the historical Church.

That first trip, we were driven through the site to get to Lorna's museum. And, and the

only way to describe it was gutting. Uh, the, bottom of your stomach dropped out.

It was, it was shocking how different it was from site to site. And how different the recovery outcomes were, or the salvage outcomes I should say.

Jayme

Conservators like Heidi and Kasey are experts at dealing with contamination. I’m meeting Heidi in Vancouver at the Museum of Anthropology, which is closed for seismic upgrades. Because of the loud construction noise, we’re meeting in the museum’s cavernous basement in the textile storage room. To enter the room, I walk across a sticky mat designed to remove bugs, dirt, or bacteria from my shoes and protect the delicate collections from outside contaminants. But the objects in such collections can themselves also sometimes be contaminated from historic conservation practices (like dousing objects in toxic chemicals) or from the heavy metals used in old bookbinding practices.

Kasey

Anyone who had access at that point had to be with an escort. We had masks on our faces from the time that we turned off the highway.

Jayme

Even for conservators trained to work with contamination, the learning curve to work in the Lytton burn site was steep.

Kasey

This was over the top of anything that we had done before. And because of the level of contamination, the hazard involved, there were very specific protocols - they had to train us in the use of these really heavy duty yellow rubberized suits. It had the masks and the goggles and the hoods and, several layers of gloves and everything was taped up so that there was no chance for any nasties getting to our bodies. It requires two or sometimes three people to get each person into this equipment. And then out of it again.

Jayme

Conservators spent a day and a half at Lorna’s site, descending in the ash-filled outline of

the museum and its basement, sifting carefully through the site for any objects

that survived the fire.

Kasey

There was a lot of rubble, a lot of cement and stone and ash, as well as the remains of metal display cases and melted glass.

Jayme

It was initially a very slow process to find a way through the remains of the building safely and without risking further damage.

Heidi

When we got there, it was three months later. So, all of that sediment had been rained on and settled and compacted.

Kasey

There was this incredibly irregular surface with holes underneath. You didn't know where

your foot was going to go through, or where you were going to trip on, on something that you couldn't see because it was just out of your line of sight. So, uh, a lot of the first day was just spent clearing a pathway and making it safe to be down there. It wasn't really until the second day that we started finding things.

Jayme

Conservators worked closely with local stewards in the recovery process. Both Kasey and Heidi reflected on how integral Lorna was to the salvage operation at the Lytton Chinese History Museum.

Kasey

It was so important that Lorna Fandrich was there with us. She was our consultant. She was

Really the ring master for the whole operation.

Heidi

Lorna, for example, drew us a map. When we got there to say, all right, here's the staff room. Don't worry about that area. Here's the collection storage area. When you get down there, this corner is more important than that other corner. And then also critically, as we were able to recover items from the site and bring them up to the surface, Lorna was the one who would be reviewing everything and making decisions on the spot about what would be cleaned and retained versus what would be considered, uh, not keepable.

Jayme

As conservators brought objects out of the site, they were carefully washed, sorted, and packed away.

Kasey

We had to remove these from the heavily contaminated basement, and they were brought up to the people, um, on ground level, where we'd set up a succession of wash basins.

So decontamination was our, our main goal there. We weren't doing conservation treatments like we would normally do in a lab. We weren't mending things and we weren't even really cleaning them we were rinsing them off. We were helping Lorna to identify things that were

encrusted with dirt and ash. So that helped her decision making process. And we were also creating a discard pile. So, a lot of what we brought up, it was in such bad shape that Lorna said, No, I can't use that, you know, it's really not exhibitable.

Lorna

That's an oxen shoe, half of an oxen shoe. I think they're hard to come by. And, uh, I don't think I'll find another one. It's part of the, you know, wagon road gold rush story to have those. So I'll keep that one even though it's very damaged.

Jayme

Although many of the items that the team recovered were damaged beyond use, Lorna was able to salvage around 200 pieces in various states—including several so-called “railway teapots.”

Lorna

Those teapots were important to me. They're called railway teapots. And it's because at the top they have this little design, two parallel lines with lines like this. I don't think it has anything to do with the railway, but people call them that. But they were commonly imported during the railway period.

Jayme

Heidi describes her memory of bringing one of these tea-pots out of the site.

Heidi

We brought one out and it looked like a bit of an alien when we brought it out. It had this

mass over top of it. It turned out to be a melted glass display shelf. So the, the wonderful thing, the conservation thing is that the melting temperature of the glass was lower than the glaze itself.

Jayme

The railway pot was glazed in tin, which meant that unlike some other ceramics, the glass did not fuse to the surface and instead might have actually protected the teapot, but it did pose an unusual recovery challenge.

Heidi

Because of that different melting temperatures, we were able to get that glass sheet off very easily and there was absolutely no impact to the glaze itself.

We were looking at it thinking, Well, how the heck are we going to get this glass sheet off because it was molded around it? But we could see it wasn't fused. And Tara, the lovely paper conservator, who's not an object person, came up with a hammer and said, I can get that off.

And she tapped the glass sheet with the hammer in the perfect way and it just shattered and broke right off. And then I was left standing there with a perfect teapot. Only a paper conservator would have done that.

Jayme

Heidi and Kasey are conservators trained in and committed to the protection, restoration, and responsible management of cultural material. But as they described the process of removing objects from the Lytton burn site, they dwelled less on the challenge of returning objects to their original states, and more on the connection between the recovery of objects and the recovery of the community. They reflected, for example, on how as objects came out of the ruins of her museum, Lorna herself seemed to grow.

Kasey

We first got there, she was devastated more than anybody. And you could see that in her posture and the look on her face and just the way she was speaking. She was very withdrawn from the whole operation. There were several Eureka moments where there's something here, there's something here, and we'd get very excited and we'd call Lorna over to look down and as we started to bring things up, you could see her posture sort of straighten up, and her speaking and decision making start to strengthen, and with each item that we brought out of the basement, she was more of a participant, and then she was a leader.

You know, our initial aim was capacity building and trying to spread the expertise and bring it to local communities so that they had what they needed in the event of a disaster.

And I think more and more it's become something a little softer than that and it's more about connecting with communities and helping them to heal after a disaster. Because so much of that healing process is reconnecting with even shreds of their material culture that was salvaged. And dealing with that emotional tragedy and upheaval and helping that, just in a very small way, that rebuilding process so that they can get back to some kind of normalcy.

Jayme

Even the broken objects conservators uncovered at the site held promise for remaking the Lytton community.

Heidi

There was this little shard of a porcelain teacup with a white, with a blue painted flower on it. And it was a tiny cup, and it was, it was broken, there was only a section of the cup and I thought, well. I'm sure Lorna isn't going to want this, but I'm going to send it up anyway because the flower is so beautiful and I didn’t think about it again until I heard that Lorna, as part of the sorting process, when she found it, was delighted because it was an extremely rare pattern. And, uh, I'm not sure if it was this one or another one, but it had already lived through another cataclysmic event of some kind, and this was the second time she was seeing it. And it, it brought her much joy.

[music]

Lorna

It's just a matter of getting, getting to that step.

Jayme

Lorna plans to rebuild the museum and hopes to break ground this spring of 2024.

Lorna

I've been just stalling, waiting till they say, okay, you can actually put in a building permit because there was a huge change with the bylaws between the old council and the new council about what would be required.

Jayme

It’s been a painstaking and at times exasperating project. As with the decontamination process, there have been ongoing delays in all aspects of rebuilding, from permitting to bylaws to new environmental building requirements. In the meantime, Lorna has been gathering new objects for the new museum.

Lorna

Some of the other museums were very helpful to me, saying that they had, um, more pieces than they need and would I like them.

So I've been given some of those already. Some of them are waiting until I have a space. Um, several individuals have sent me items. There's a few more coming, like a family who's sending me their mom's wedding dress and a whole pile of her things. She's 95 and having to leave her home, so they're just waiting for me to say I have a good space to keep them.

Jayme

The new museum will be an amalgamation of objects that survived the fire, reproductions from digital images of lost artifacts and documents, and a significant number of new and often donated objects. While the rebuilt collection will be materially different from the destroyed museum, Lorna hopes to steward the same stories.

Lorna

So now I just have the photos without the scans. And so they're not the best, but they'll still tell the story. Right? I can still put them in in that regard.

So there's about 500 pieces I have now, and so they will not be from the Lytton area, but as you know, in every mining camp and every railway camp, the same items were used. So if they're looking the very same as items I had, I'm accepting them and I'm sure I'll be able to tell the story by just, um, perhaps buying a few significant pieces from a couple collectors I know.

I was able to get these little game buttons. So they would've played, um, gambling games with these, and they're made of glass, and they would have a set of black ones and white ones.

Jayme

One small section of the new museum will exhibit damaged items that help tell the story of the Lytton fire itself.

Lorna

We were able to pick out about 200 items. I would say about 40 of those would be, um, good to display other than I'll do one small cabinet that'll talk about the fire. I don't want the fire to be the focus of this museum either.

Jayme

As much as the fire has permanently altered the museum and its collection, Lorna emphasizes that she doesn’t want disaster to overshadow the purpose of the museum itself: telling the story of Chinese settlers and migrant workers in the area. Lorna stresses the imperative of telling that story as vital to how she approaches recovery. Unlike some of the other cultural stewards we’ll hear from in the coming episodes, for Lorna, objects can be replaced provided they can convey and carry forward the same story.

Through this lens: objects spark stories in off-hand encounters or in a joke between siblings; stories gather around objects in the fabric of communities, in family lore, or in entwining people together in their common experiences. For Lorna, it is these kinds of stories that provide the foundation for a community’s recovery from a devastating event like the 2021 fire.

<recorded question>

Jayme

How has the experience of the fire changed how you think about, um, cultural collections?

Lorna

Uh, I think it just pointed out the importance of them in any community because of what we've lost. So in any community, that is your history. That's our history for heaven’s sake. Yeah, even if local people didn't spend a lot of time in the museum, they did spend some time and that was their family's history because so many families here were longstanding

I think it's really important because yeah, we have, we have a past, you know, we're not just starting today.

Jayme

The Lytton Chinese History Museum lost most of its collection during the 2021 wildfire. The institution’s recovery has faced many setbacks. The museum’s rebuilding is more than the recovery of an under-told history—one gathered from among objects in trash heaps, objects littered in the landscape, or guarded in family collections of those dispersed from the Lytton area—the remaking of this museum also participates in a long history of surviving contamination in this landscape.

[music]

The traditions of that survivance have taken many forms; for Lorna and the Chinese history museum, stories are the basis for the survival of a community with a complex history and complex relationships. Telling stories and histories forms the basis for making community in an altered landscape, even as the threat of more fires lingers.

Jayme

In the coming episodes, we’ll dive into more of the archival ecologies of the Lytton area and its cultural collections. Stayed tuned for this ongoing exploration of how cultural histories, memories and practices are changing with the weather.

Archival Ecologies is created and hosted by me, Jayme Collins, and is a production of Blue Lab at Princeton University. For their support and expertise, we also thank, at Princeton, the High Meadows Environmental Institute, the Humanities Council, and the Office of the Dean of Research, as well as Kouvenda Media. This project has also received invaluable research support from Jamie Rodriguez, Kavya Kamath, and Molly Taylor. Voiceover by Mario Soriano. Music by Hamilton Poe.

In the wake of the fire, concerns about contamination slow down efforts to salvage material from the burn site. The BC Heritage Emergency Response Network aids Lytton’s organizations—especially the Lytton Chinese History Museum, founded by Lorna Fandrich—to access and recover material from the sites. Most of Lorna’s collection burned, but she was able to recover about 200 objects that will provide the foundation for the new museum. With a combination of salvaged and newly acquired objects, Lorna plans to rebuild the Lytton Chinese History Museum to tell the same story: the history of Chinese life in the Fraser Canyon region.

Newly acquired buttons and game pieces from Lorna Fandrich’s collection for the new Lytton Chinese History Museum. Photo by Jayme Collins.

Concrete, rebar, and plastic litter the site of the former Lytton Chinese History Museum. Photo by Jamie Rodriguez.

Lorna Fandrich giving us a tour of the site of the Chinese History Museum, which used to sit in the large hole in front of her. The large hole is evidence of the contamination remediation process. She will rebuild at the same site. Photo by Jamie Rodriguez.

Episode 3: The Place of Objects

Archival Ecologies Episode 3: “The Place of Objects”

Full Transcript

Jayme

The wind in Lytton is constant.

It blows up the canyon, from the rich delta where the river meets the ocean in Vancouver, from within the territories of multiple Coast Salish peoples. This is where the salmon start their cyclical return up the river to spawn. Moving east, the wind blows through the fertile soils of the Fraser Valley, and then follows the river as it turns abruptly north, moving through the quickly transitioning climates and ecosystems of the northward river: from dense west coast Douglas fir, cedar, and maple rain forests to the arid pine and sagebrush desert ecosystem of Lytton. While it has been known as the Fraser River since the explorer and fur trader Simon Fraser navigated it 1808, the river, in fact, has many names along its length.

Lytton has always been a crossroads—rivers, railroads, and highways meet here. The wind, though, gathers a different topography, embodying connections between the river, oceans, mountains, and the fertile agricultural land as well as the diverse ecosystems that support life here through patterns of sustenance and trade.

Every fall, the salmon return to the river, and the Nlaka’pamux people hang its meat in the wind’s path to dry it and preserve it for winter.

John Haugen

When I was leaving my house the day of the fire, I remembered there were these two big baskets in my bedroom downstairs and I said, I don't own those baskets, and so I went running back downstairs and grabbed them, and then they were the only two baskets that survived the fire at my place.

Jayme