Season 2

An original audio story series led by Mario Soriano

Season 2: Conversations about retreat

You can find Carried by Water on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music. and iHeartRadio.

Carried by Water explores stories of movement revolving around water as a force of nature, a resource and a pillar of well-being. Season 2 brings us to communities in New Jersey and Delaware where homeowners and scientists are grappling with the question of relocation in the face of increasing flooding and sea level rise. Through stories of people making real-time decisions of whether the advantages of remaining in place outweigh the risks of repeated disaster, we discover evolving ideas of climate adaptation, home, identity, and resilience.

Credits

Carried by Water is created and hosted by Mario Soriano with season 2 research, writing and production support from Asela Perez-Ortiz, Hannah Riggins, Farah Arnaout and Jayme Collins. Carried by Water is a production of Blue Lab at Princeton University. Additional support at Princeton has come from the High Meadows Environmental Institute, the Humanities Council and the Office of the Dean of Research. Copyright 2025 Mario Soriano and Blue Lab.

Episode 1: This was not home for us

Carried by Water Season 2, Episode 1: “This Was Not Home for Us”

Full Transcript

Patricia: This is crazy. And I asked my husband, I said, have you been back? He said, I haven't, surprisingly. Because he would be the one to always just come down. He would just get his chair and just sit outside or sit in the backyard. He said he hasn't.

Mario: Yeah, it must still be kind of emotional.

Patricia: Mm hmm. It is. It is. Definitely is. You know, um, when you work your whole life and you absorb all of your savings and your 401k and your pension, and you, you know, you withdraw all of that to purchase your first home. And then to see it all just go in a matter of hours, it's hard. It's hard.

Mario: So this was your first home.

Patricia: This was our first home. And we were only here for nine months exactly. To the day. Nine months. Yeah.

~

Mario: Welcome to Season 2 of Carried by Water. I’m Mario Soriano. This season, we explore stories about retreat. We examine how increasing climate disasters are driving people to grapple with difficult questions of whether the advantages of remaining in place outweigh the risks of repeated disaster. Stories of how flooding and sea level rise are reshaping ideas of home, identity, and place in communities that have themselves been shaped by their location on the water’s edge.

Episode 1. This was not home for us.

When Patricia Montrevil-Thomas bought her house in Manville, New Jersey in 2020, she envisioned that it would be the home where she and her husband could spend the rest of their lives.

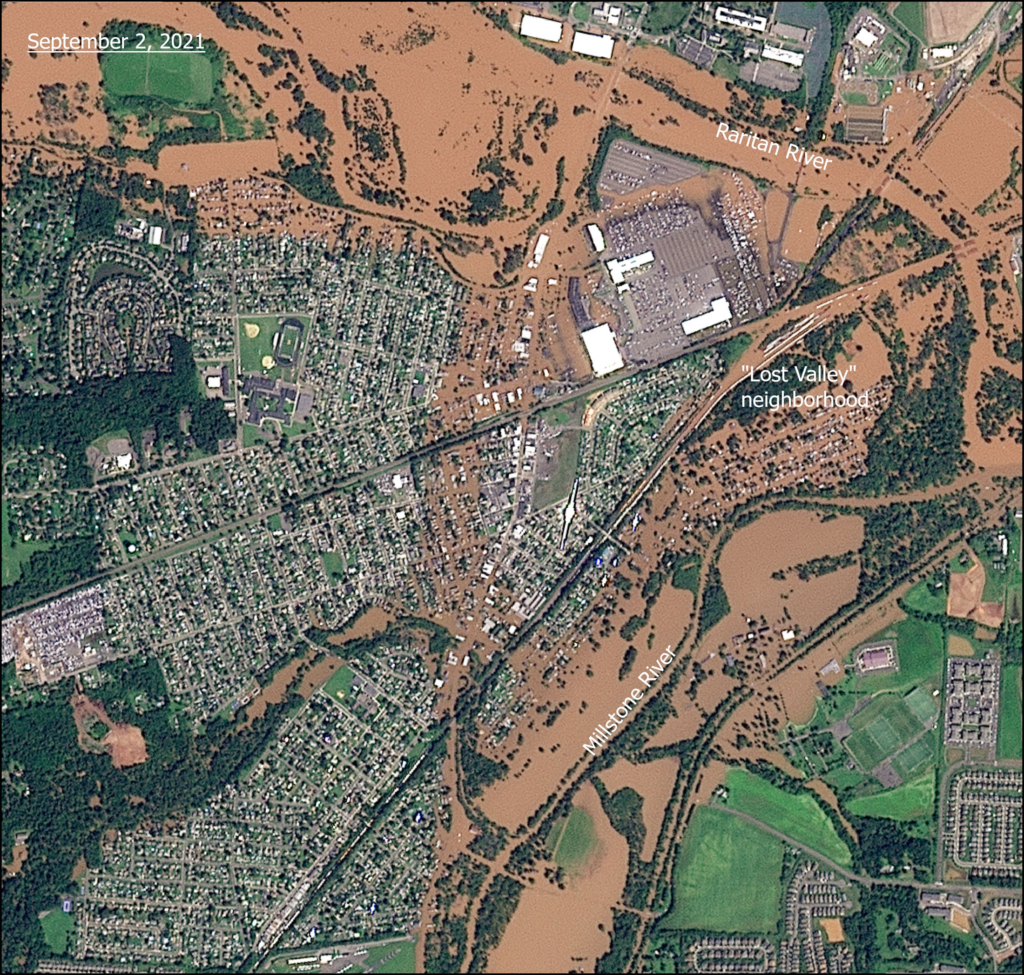

That dream lasted only for nine months, as torrential rains from the remnants of Hurricane Ida flooded their entire neighborhood in September 2021. She and her family were rescued out a window from their second floor.

~

Patricia: When Hurricane Ida settled over New Jersey, for however many hours it did, we did not expect the water to be that high. We were in the basement, we were cleaning up, and the water just kept coming in, kept coming in, and I'm like, something's not right. So I came upstairs,

I looked, I said, oh shit, we're in trouble.

It was too late. The water was already coming up the basement steps. The wall had already caved in. It was just, everything was just too late. So we just went to the second floor and we stayed on the second floor until we got rescued a couple of hours later.

All I remember is the bulldozer, us jumping in, throwing the dogs in, and being carried out in a bulldozer. I've never rode in a bulldozer before, but that was my first experience riding in a bulldozer.

~

Mario: After being rescued, Patricia, her husband Omar Thomas, and their two children had to live in their 4-door sedan for two and a half days until the water receded. She told us she and her husband had to stay calm for their children’s sake, but they couldn’t hold back their emotions once the kids were asleep.

~

Patricia: When they would fall asleep, we would, you know, get out the car and we would just cry and we were upset. We were really upset. But we had to keep it calm for them. And yeah, 2-and-a-half days we lived in our car. And when that water receded down on Main Street, we gunned it. Gas light on, everything. We gunned it till we found the first gas station, filled up, jumped on 78, and we went straight to Maplewood to my sister's house. And we lived there in my sister's house for three years.

~

Mario: As Patricia was telling us more about this experience, her husband Omar arrived to join our conversation. He immediately noticed something that brought back memories.

~

Omar: I had that jacket.

Mario: Oh.

Omar: Remember that jacket?

Patricia: Yeah. It's in the Raritan River.

Omar: It's around here somewhere. <laughter>

Mario: Could you tell us a little bit about your life here before the flood?

Patricia: I would get up in the mornings before everybody else. And I would sit there and I would literally watch the sunrise. I would take pictures.

Omar: I was already at work.

Patricia: Yeah, you were already at work. <laughter> Living in the house. It felt like home. We were home, you know. We felt like we were coming home every day. And the summer that was our first summer there. Um, summer was amazing.

Omar: Awesome.

Patricia: It was awesome. We had a fire pit, we had a grill, trampoline for the kids, water slides. We lived. Had fun, you know. Had cookouts, parties. I think everybody was happy. Everyone was happy. I would say. Everybody was happy.

And then, you know, the flood happened. We moved out. Stayed with my sister. And things, you know, was okay because we had hope. We really did. We had a lot of hope. We had hope that we were going to come back home. We had hope that everything was going to work out and that, all of our hard earned money that we put into this, you know, would just fall into place and we would be able to just come back home, but reality hit and we, we thought about it and we just thought about all the different scenarios, and we just realized that this was not home.

This was not home for us.

~

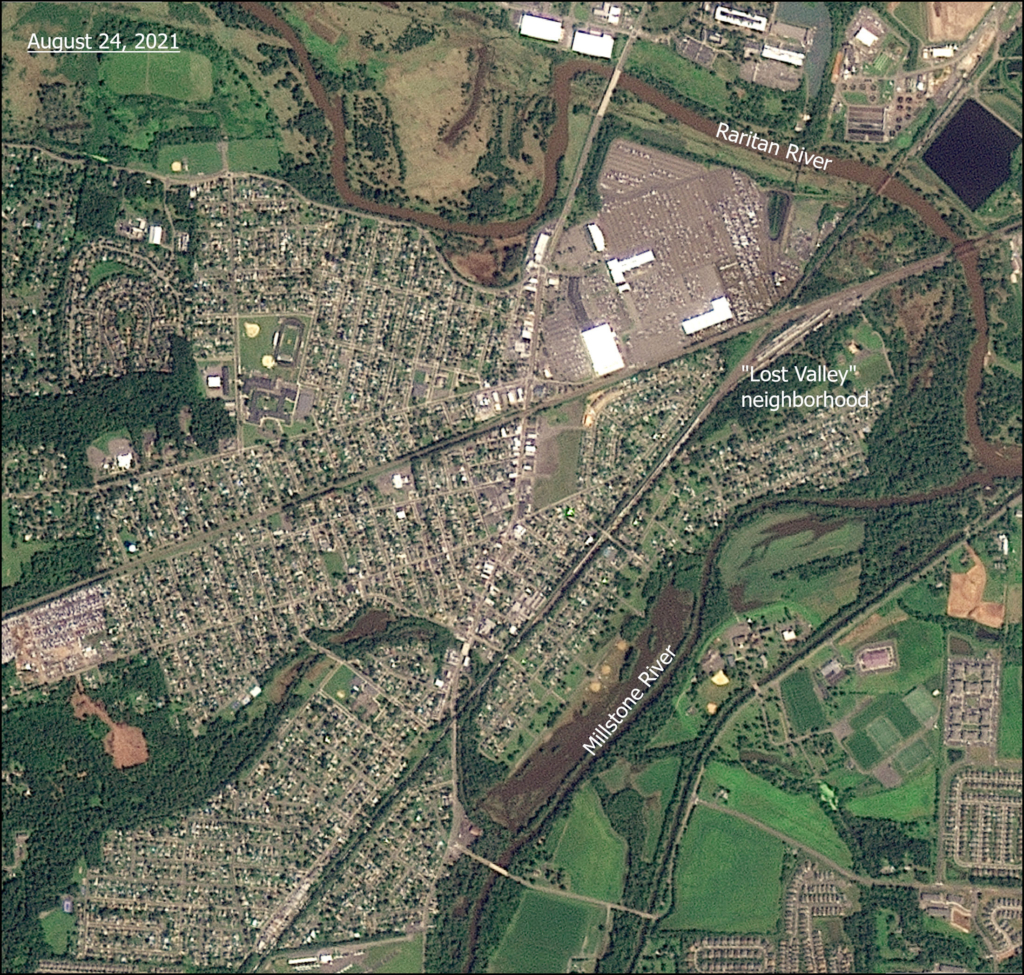

Mario: Patricia and Omar’s old house is in what’s known as the “Lost Valley” section within the town of Manville in central New Jersey. Manville, a town of almost 11,000 people, lies right where the Raritan and Millstone Rivers meet. Historical records document at least 127 flood events that have impacted the town since 1903. The Lost Valley neighborhood, with its location at the heart of the floodplain, has experienced repeated inundation. The last major flood event before Ida was Hurricane Floyd in 1999.

The town has tried to ask the government for help by building infrastructure to address their chronic flooding problem. Their request was denied. Here’s what the official feasibility study concluded:

“Various measures (e.g. levees, channelization, raising of individual structures, etc.) were considered, screened for applicability, and developed into alternative plans to provide flood risk management within the Borough of Manville.

Unfortunately, economic analysis has demonstrated that all formulated alternative plans have Benefit-Cost Ratios less than unity and thus no alternative plan has been identified that favorably contributes to National Economic Development. Therefore this report recommends that no Federal flood risk management alternative plan be further developed and implemented.”

US Army Corps of Engineers, Millstone River Basin, New Jersey, Flood Risk Management Feasibility Study, Feasibility Report, February 20 16

Mario: With large-scale flood control infrastructure no more than a distant pipe dream, and with climate change threatening to bring more extreme weather and flood risks, residents are weighing the difficult decision to stay or leave what they once envisioned as their long term home.

One option they have is to rebuild in place and elevate their homes above the previous flood level. This is actually a requirement by flood insurance.

The other option is to sell their property and move elsewhere. Some people opt to sell in the open real estate market. Other homeowners sell to the government, a process that is often known as a buyout. Patricia and Omar opted for a buyout after their experience.

New Jersey has one of the oldest state-run buyout programs in the country, a program called Blue Acres. We spoke with the program’s manager.

~

Courtney: My name is Courtney Wald-Wittkop. I have the privilege of managing the state of New Jersey's Blue Acres program. Blue Acres is a state led voluntary buyout program. It's administered by the Department of Environmental Protection here in New Jersey. We only work with willing sellers. Uh, we acquire homes from those willing sellers. Uh, we demolish them and we create open space for flood storage purpose.

~

Mario: Blue Acres was established in 1995, and had done some buyouts in partnership with the US Army Corps of Engineers in the late 1990’s. However, it wasn’t until the 2010’s when it started obtaining funds from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) that the program really took off. To date, Blue Acres has acquired over 1,100 properties amounting to over 210 million dollars. Homes acquired by Blue Acres are demolished and permanently designated as open space. No future construction is allowed on the lots.

The program is nationally renowned for its case managers who help interested homeowners navigate the various state and federal rules. Courtney described the buyout process as follows:

~

Courtney: Every property is valued by a licensed appraiser in the state of New Jersey. Homeowners get a copy of the appraisal. There is a requirement to do a duplication of benefit review. This is, especially if we're using federal funding, we have to kind of ask them what kind of structural assistance they received.

Sometimes the federal funding sources will dictate what your date of value is for your appraisal. And so it's a little bit of adding, subtracting thing that has to happen if the buyout offer is based on a pre-storm value. When we talk about post-storm values, it's much simpler. We're valuing it that day that the appraiser’s out there.

In either case, we're very transparent with the homeowners. Your funding source is X and the date of value will be Y. And you know, we try and make sure that the case manager’s very clear about that at several different points before the value happens.

~

Mario: If that already sounds kind of complicated to you, we’re on the same page. I can imagine how helpful a dedicated case manager would be at this point.

Courtney says that after doing all this accounting, an offer is made verbally and in writing, and then homeowners have two weeks to respond.

~

Courtney: They don't have to accept in two weeks, but they have to respond, meaning they have to say something like, I'm still thinking about it, or I don't think this is enough. And we do have appeal processes in place so homeowners can get their own appraisal. And we can kind of triangulate a value. We can also revisit duplication of benefits, so if they have additional receipts or information that they want to share, we can revise and update offers a few times.

~

Mario: Once the offer is finalized, homeowners have to decide when they want to close the deal.

~

Courtney: Some people are super eager and they want to close as soon as humanly possible. Other people want to find replacement housing or they've, we've heard all kinds of stories. Everything from, you know, my child wants to graduate high school and, you know, they're a senior. Can we just finish the school year? Things like that. So we try and be as accommodating as we can. But we also want people to realize that sometimes we have grant requirements that dictate that we complete certain things in certain time frames. So we may have to kind of inspire people to make a decision and figure out what they want to do.

~

Mario: In the past, closing would be the final interaction between Blue Acres and the selling homeowner. The focus was on just getting them out of the flood-prone area. And that’s understandable.

The problem is, we then have no way of knowing if the selling homeowner moves to a similarly flood-prone area. We wouldn’t know if the buyout truly reduced their flood risk. Recognizing this, Blue Acres now asks homeowners where they are going to ensure that people don’t find themselves at risk of flooding once again.

Patricia and Omar told us their application took two and a half years despite being promised a quicker process considering their son had a disability.

~

Omar: They told us we'd be expedited, but two and a half years is a regular, is their regular time. The expedited would be three to six months. Two and a half years later is what their process is anyway. That's their whole process. They said it in the uh, meeting. It's gonna take this amount of time. Get your house together, do what you gotta do, then move back into your home, we'll be in touch with you. Basically is what it boiled down to. We were expedited because of Adam. But turned out to be the same amount of time as a regular applicant.

~

Mario: “Do what you gotta do to move back into your home, and we’ll be in touch with you.”

This meant making repairs to the damaged structure, replacing all your furniture and lost belongings, and above all, still paying your mortgage for the time being. On top of all that, you might also need to pay rent for a place while your house is still unlivable. Waiting for a buyout for more than a couple months sounds quite expensive.

Still, Patricia and Omar did what they had to do over those two and a half years. They still paid their mortgage even while they were living with Patricia’s sister. They were making repairs to their home.

When their Blue Acres application was approved, they stopped doing the repairs. They never got to a point when they were able to move back in.

~

Patricia: The one thing I am going to say about Blue Acres is, um, it's a good program. It's a good program, but I think they can do some changes within for sure. Um, and one of them is, if you know that you're going to help out the applicant, pretty much take into consideration how much that applicant or homeowners kicked out before the day of closing with Blue Acres.

So, let's say you accept their application in January and you close out in October. Still consider the fact that 10 months they still were paying a mortgage, and include that in the buyout program. You know what I'm saying? ‘Cause we paid the mortgage for two and a half years. Two and a half years, almost three years, we were still paying, you know, a mortgage and that was a lot.

Omar: Or talk to the mortgage company and help out.

Patricia: Have them stop .

Omar: Stop or freeze the uh, payments. ‘Cause we weren't occupying the property, you know?

~

Mario: There was some belated good news on this front. At the end of October last year, a law pausing mortgage payments for Hurricane Ida-impacted homeowners was passed. This law pauses mortgage payments for qualified homeowners for one year. While it came three years after the storm, this mortgage forbearance law is expected to provide some much needed relief for homeowners who are still trying to recover.

When I first heard about Blue Acres, I was quite intrigued by its homeowner-driven approach to relocation. I was honestly a bit skeptical. After covering the long-term outcomes of mandatory relocation programs in the Philippines after typhoon Haiyan last season, I recognized the multiple facets of losses that being displaced from home meant for people.

Relocation as a response to climatic hazards, whether enacted through mandatory approaches like what we covered last season or voluntary home buyouts like Blue Acres, can be viewed as an example of managed retreat.

The managed retreat handbook reads:

“The three primary options to respond to a rising sea and increased threat of hurricanes are protection, accommodation, and retreat.

Policy makers will need to turn increasingly to land use reform and a policy of managed retreat from the shorelines. These policies avoid disasters by building resilience, preventing or limiting coastal development in vulnerable locations, and reducing the impact of coastal hazards on infrastructure. Such proactive non-structural solutions are often more cost effective than coastal armoring over the long-term as they do not require on-going maintenance, re-building, or repair.”

- Managed Coastal Retreat: A Legal Handbook on Shifting Development Away from Vulnerable Areas, October 2013

Mario: The author of this handbook is lawyer and University of Delaware professor AR Siders.

~

Siders: I study climate change adaptation, specifically looking at decisions like managed retreat, relocation, coastal resilience.

I started thinking about managed retreat after Hurricane Sandy. I was in New York at the time,

And one of the conversations that kept coming up was how we rebuild, not whether we rebuild, or where do we rebuild. I spent the next year documenting examples of managed retreat around the United States, and how they had been done, what some of the most maybe creative, most common ways, what lessons were learned. And that turned into the Managed Retreat Handbook. Uh, so that's what really kicked everything off.

~

Mario: Managed retreat is an umbrella term for various policies that aim to relocate populations and infrastructure away from areas that are vulnerable to hazards such as repeated flooding, sea level rise, and increasingly, wildfires.

The term managed retreat is not uncontroversial. Synonymous terms include “planned relocation” or “strategic retreat”. For Siders, the aversion to managed retreat, both the phrase and the practice, needs to be reexamined.

~

Siders: On some level, I think you can call it whatever you want, and as soon as people realize that what it involves is homes moving or communities moving, there's still going to be resistance to the idea. So the terminology matters, but at the end of the day it's also about that core that's going to be really difficult to talk about no matter what language we use.

It's a shame that retreat rhymes with defeat. People think of retreat and they think of loss. They think, oh, we're retreating because we lost that battle. We lost the effort. They think of it in terms of, you know, we're giving up. And so for a long time there was a discussion about whether managed retreat was even properly considered adaptation or whether it's a failure to adapt, right? You're retreating because you have failed climate adaptation. And I thought that was so fascinating. Um, I guess because there are so many classic examples of retreats that are not losses.

You know, I'm here in Delaware. You think about Washington crossing the Delaware River. Famous retreat. Not a war we lost. Right? Or Dunkirk and the evacuation across the channel. Famous retreat. Not a loss for the allies.

There was loss involved, but it's an interesting way to frame it, right, that this is somehow giving up or defeat when in fact, for many of these examples, it's not. It's about re-evaluating whether or not you're moving in the right direction, whether or not this was the right front to attack, whether this was the right course of action. And I think that reframing is what I find so fascinating about Managed Retreat.

~

Mario: Siders has long argued that managed retreat can be an effective approach to climate adaptation. She believes societies must be proactive in grappling with the prospect of climate change making some places simply too risky to live in in the future.

Courtney shares this sentiment.

~

Courtney: There are going to be people who are adamant about staying. What happens? You know, what do we do? Nobody wants to say, well, we're not going to help them in the next storm or something like that. But I think all of us as taxpayers also have to ask ourselves, like, is that the best use of our resources, right?

There's this thing out west where if you go skiing out of bounds and you need to be rescued, they actually give you a bill. They literally mail you a bill for the services of coming out to get you. And I think there's something interesting there. And I'm not saying we should do this, but like this idea of like, if everything in its power is sort of saying this isn't smart or safe. Are we going to start saying to people, here's an affidavit to sign, you're taking on this risk of staying here? Because I think at some point, first responders and government entities have to question the cost-benefit of letting people stay. And I think, while I don't want to necessarily advocate for forced retreat or forced buyouts or anything like that, I think we want people to understand that there is a consequence.

As Americans, we love our freedom of choice. We do. But there are sometimes other consequences that people have to understand, go along with your choice, right? And so how do we make people kind of more aware of that?

~

Mario: Patricia Montrevil-Thomas sometimes worries about her former neighbors in the Lost Valley.

~

Patricia: I would hate to, you know, see these homeowners lose their home. But at some point you're gonna have to because this is the environment that we're in. And global warming is real. And unfortunately, the water wants its land. It wants his land back.

~

Mario: Patricia and Omar told us the moving to Manville was a choice they made freely. Moving out of their house after Ida, however, was different. After losing so much and thinking about the possibility of it all happening again in the future, they felt that they had no other choice.

The house they poured all their savings into and once dreamed of as their forever home has been acquired by the state and is up for demolition in the coming weeks.

Siders recognizes that retreat will entail some inevitable losses, both emotional and material.

~

Siders: Loss in this context is not about winning and losing. It's about grief. Uh, it's about losing connection to things that matter to you. It's about loss in connection to place. Loss in community. Uh, sometimes loss in value. Like if you think about loss in home value or financial losses. But oftentimes when we talk about loss in managed retreat, we're talking about the loss that people suffer from having disconnect from the places and the people that they really care about.

Most people live in a place because there's all kind of advantages for them living there. Maybe it's that they love their neighbors, maybe it's that they love their commute, maybe it's that they love the local park. Whatever it is, there's something they're connected to that made them want to live there in place. Maybe it's just that it was affordable. That's a good thing too. So, when we think about relocating, it's questioning which of those ties are you breaking? And which of those ties matter?

~

Mario: Courtney suggests that perhaps there are ways to alleviate such losses with careful planning of what becomes of the space.

~

Courtney: Ultimately, if we have to lose it, if that area that's really relevant to you is just not safe for you to live in, how do we make it something else that you can still value?

Most of the properties we acquire become open space with local management, so they're accessible, but probably not when it's flooding. So how do we make sure that it's there for people to still kind of connect with?

Maybe not as home, but as near home or adjacent to home and things like that. And so I think it's a lot about having those conversations up front, being proactive about why it's important and what you can do and exploring a lot of different ways to document and memorialize the relevance.

~

Mario: Patricia and Omar and their children moved into their new place just four months before we met up for this interview. They said this new house is not in a flood zone, but they couldn’t yet help but be hypervigilant whenever it rained.

~

Patricia: The rain that we had, you know, this July, August, and this September, all that rain we had. I used to just open the back door and just look. And then I saw like a puddle and I'm like, Omar, it's a puddle, it's a puddle back here. And he would come and he's like, it's okay.

Omar: So every time it rains, we're on it. Like it rained for five days.

Patricia: Oh yeah. That one. Yeah.

Omar: The last time it rained, it rained for five days and we were just like, hmmm. And I'm just looking, looking, looking, looking, looking.

Patricia: I'm like, did you check, did you check the sump pump? Is there water in there? He's like, there's no water. It's going out. Okay.

~

Mario: I asked them if they feel like they are home.

~

Omar: I'm home. Why do you think it took me so long to get here?

Patricia: Uh, yeah.

Omar: I'm home, yeah.

Patricia: We're home.

Omar: The leaves are a lot, but it keeps me busy. You know, it's different. We have deer, like we had it out here too. So yeah, we've kind of moved into like, kind of like the same type of,

Patricia/Omar: same type of area. The deer, the grass, the skunks, pretty much. The trees, you know, just

Omar: Home.

Patricia: Yeah.

~

Mario: Next time on Carried by Water, we’ll look at the broader set of actors and outcomes of managed retreat.

~

Elliott: Same policy comes into the same disaster zone. But when it enters into communities that have been historically unequal in terms of access to resources and expectations of public infrastructure. That same policy can end up in very different results. And so, is that a matter of intent? Do we think FEMA is intending to do that? No, but it is a matter of consequence.

~

Mario: Carried by Water is a production of Blue Lab at Princeton University. The podcast is created and hosted by me, Mario Soriano. This episode was written by me, with production support from Asela Perez-Ortiz. Additional background research by Hannah Riggins and Farah Arnaout. Voice-over for archival materials by Asela Perez-Ortiz and mixing by Hannah Riggins and Asela Perez-Ortiz.

Insights from my conversations with Nathan Jessee and Kanako Iuchi also informed this episode.

Allison Carruth is the director of Blue Lab, and Barron Bixler is creative director.

Visit our website, bluelabmedia.org, for more information and photographs for this episode.

Until next time.

~~~END OF EP01~~~

How does one's experience of flooding reshape their ideas of home, safety and community? We hear from homeowners Patricia and Omar as they recount their story of Hurricane Ida and their subsequent decision to sell their home to Blue Acres, New Jersey's nationally renowned, state-run program for voluntary buyouts of flood-prone properties. We also talk with Blue Acres program manager Courtney Wald-Wittkop and climate adaptation expert A.R. Siders about the broader ideas of managed retreat and loss in the face of more extreme flood risks.

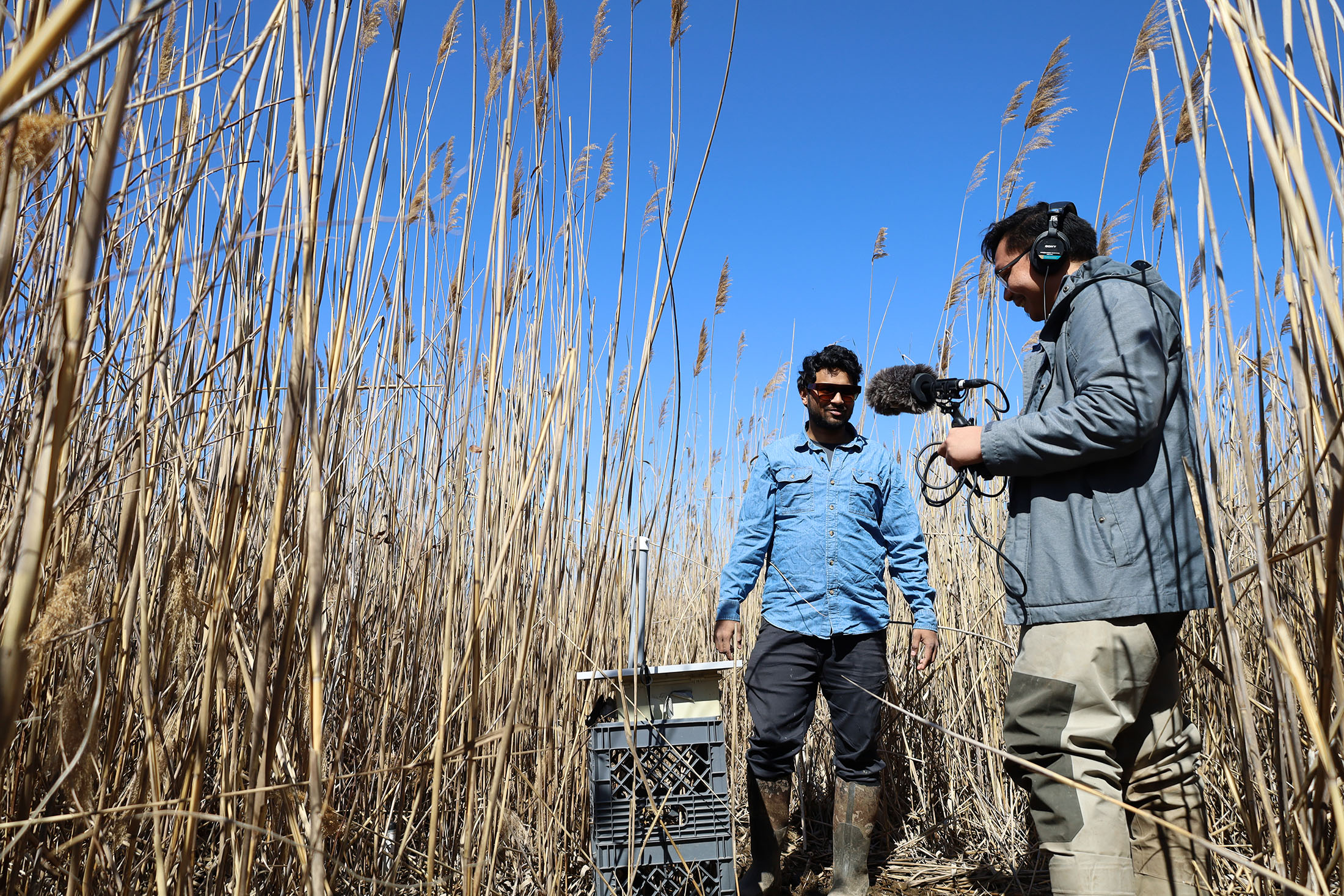

Patricia Montrevil-Thomas looks into her former home in Manville, New Jersey. photo by Asela Perez-Ortiz.

Omar Thomas and Patricia Montrevil-Thomas speak about their experience selling their former home to Blue Acres, a state-run buyout program for flood-prone properties. photo by Asela Perez-Ortiz.

Satellite Images of Manville, NJ Before and After Hurricane Ida

Episode 2: A matter of consequence

Carried by Water Season 2, Episode 2: “A Matter of Consequence”

Full Transcript

Mario: In the early spring of 2015, Monique Coleman’s house on Heidelberg Avenue in Woodbridge, New Jersey was demolished. It was among the first properties acquired by the state’s Blue Acres program in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy.

~

Monique: My family sat and watched our house being razed. I think we were one of the first houses to be demolished. Not the first, but one of the first. So they kind of made an event out of it. So we sat in our chairs in front of the property and, you know, just saw the whole process. That was really incredible to see the home that we had lived in for seven years be reduced to nothing.

~

Mario: Photos from that day show a yellow excavator tearing into a two-storey A-frame, colonial style house. Standing on the street are Monique and her family, along with city and state officials and the media, all bearing witness.

~

Monique: You see different parts of the house going down, right? And it's like, oh, that's where their bedrooms were, where they played, you know. My kids didn't really show a lot of emotion. I think they were just amazed at the whole production, right? Um, but yeah, it was a little emotional just seeing that where they had lived and spent a lot of their childhood years playing and, and growing up. You know, it was emotional, I guess, to an extent, but at that point I was just relieved that we were going to be out of the situation that we were in. And it had been a stressful, long period. So we were ready to move on.

~

Mario: When we met with her in the fall of 2024, Monique vividly recalled that her house had suffered back-to-back flooding in 2010 and 2011. Then, in 2012, Superstorm Sandy hit, bringing catastrophic flooding to her community that far exceeded those previous experiences. That was the final straw for Monique. Retreat sounded like relief.

Monique’s house was located in the Watson-Crampton neighborhood of Woodbridge Township. About 100 acres, this part of town is bounded by water on three sides: the Woodbridge River, Heards Brook, and Wedgewood Brook. Nearly a fifth of Woodbridge lies within a “Special Flood Hazard Area”, as designated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA.

In the late 90’s to early 2000’s, the Army Corps of Engineers led study after study to investigate the feasibility of doing structural flood mitigation in town. Each time, their conclusion was either that more study was needed or that such measures were infeasible.

Many in the community had voiced frustration with government inaction despite the frequency of flooding events. One of Monique’s neighbors wrote the following in a 2003 letter addressed to a New Jersey senator at the time:

Dear Senator Frank Lautenberg:

As a resident of Woodbridge Township who often falls victim to flooding as result of our proximity to the Woodbridge River, I wish to express my dissatisfaction with the decision by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to only perform further study of the flooding problem, rather than immediately begin corrective action.

Further study will only confirm what we already know...that people whose homes lie near the Woodbridge River will be in constant danger of flooding until the Army Corps acts. The problem is obvious. At this point, we need help...not further study. It is imperative that federal funding be made available to alleviate this situation, which erodes the quality of life for dozens and dozens of Woodbridge Township families.

Very truly yours,

Alberta D. Gladis

Woodbridge, NJ 07095

October 21, 2003

Despite such advocacy, no concrete measures were approved at the time. The Army Corps concluded that any flood mitigation investments were economically unjustifiable and therefore warranted quote “no further Federal interest.” end quote

After Superstorm Sandy, in 2012, the state government finally did offer something to residents of Woodbridge and other New Jersey flood-prone communities. The government’s proposal: a $300 million dollar buyout fund for repeatedly flooded homes, to be administered via Blue Acres, a state program first established in 1995.

With this influx of money into Blue Acres, both the state’s Department of Environment that administers Blue Acres and the federal agencies wanted to target for buyouts homes in contiguous neighborhood blocks. For Monique Coleman, that directive led her to organize her neighbors to come together and apply to the program collectively.

~

Monique: There was just so much that we had to do, in terms of the community organizing piece. It was knocking on doors, speaking to neighbors, letting them know about the program. This could be an option for us, but it was a community model. And also just spreading awareness about what would happen if they did stay, with the flood insurance rates promised to increase substantially because we were now clearly this high risk zone. That was an important part of our process. But it was difficult because some of the people had been there for like 30, 40 years, right? Multi generational families had been in the community for a long time. And so ultimately it really was about, for us, helping other people understand what the consequences would be of staying there. Right?

~

Mario: Monique’s and others’ grassroots efforts gained steam, and as a result, Woodbridge holds the distinction of being the town with the largest number of post-Sandy buyouts in the state of New Jersey.

In the years after the storm, Blue Acres acquired over 170 properties in the township, many of them concentrated in the Watson-Crampton neighborhood. Since the buyouts, most of those houses have been demolished. Today, a decade later, those blocks once occupied by homes have become permanent open space.

~

Monique: My kids used to go and play back there. So it was a very short dead end street. Where those posts are, was the cutoff for the block.

~

Mario: We’re standing in this open space in the place where Monique’s house stood.

~

Monique: So, yeah, this is it. We had a colonial style two story home and really, pretty nice sized property. We had a beautiful garden that my husband kept, vegetable garden that my husband kept here, and we missed that a lot, you know. But, yeah, this is it.

Mario: Was this tree here when you lived in the area?

Monique: Yeah, I'm trying to picture, yes, this was the tree that was actually… Was this on my property or was this on the neighbor's property? I feel like this tree might have been on the neighbor's property, right? Near our driveway, I'm not sure. It is hard to put everything where it was because it's just this wild land, so to speak, now.

~

Mario: Monique’s experience—of organizing her neighbors to apply for Blue Acres buyouts but also of grappling with the emotional weight of leaving one’s home and community—shows how such local, individual decisions are bound up with complex histories of places designated as too hazardous to be sustained, as ideal candidates for “managed retreat.”

If we take a closer look, who, can we say, is really managing managed retreat?

From Princeton University’s Blue Lab, this is Carried by Water. I’m Mario Soriano.

Episode 2. A matter of consequence

~

Liz: You know, you could talk about the managed part and you could talk about the retreat part. I actually felt more critical of the managed part because this idea that someone's managing someone else and that's how retreat is going to play out is an assumption that's embedded in the term and an assumption that I've tried to challenge through my own research.

~

Mario: This is Liz Koslov. Now a professor in urban planning and environment and sustainability at UCLA, Liz was a PhD student in New York City when Hurricane Sandy struck. Curious about managed retreat as a response to the disaster, she ultimately designed her dissertation around a study of neighborhoods on Staten Island, where communities were organizing to advocate for buyouts from the government. Residents of the Staten Island neighborhood of Oakwood Beach in particular took the lead in advocating for their own retreat.

~

Liz: These residents in the neighborhood who were already organized around flooding, this group that had called itself the Oakwood Beach Flood Victims Committee, and then became the Oakwood Beach Buyout Committee after Sandy. They organized a meeting. They were leading it. The media was not there. Government officials were not there. It was really a meeting for them and their neighbors to talk about, “What's our future going to look like here?” And so most people in the neighborhood encountered buyouts as an option through people they already knew and trusted and identified with. Demand for buyouts became so widespread in this particular neighborhood and really, you know, almost unanimous.

~

Mario: I asked Liz if this was an example of grassroots managed retreat. Her response made it clear that there wasn’t a straightforward answer.

~

Liz: There was a lot of debate when buyouts were first announced among the residents I was spending time with who were saying that officials at different levels of government were taking a lot of credit for something that they saw as their initiative and their plan, because they were the ones to advocate for this. But on the other hand, of course it couldn't have happened without there being a government program. So, the idea that it was sort of managed and clear-cut in the New York case was not, not my experience.

~

Mario: Similar to Woodbridge, for Oakwood Beach, a community’s voluntary retreat required both grassroots organizing and government investment and infrastructure. But even then, the consent for retreat was not universal. Only some neighborhoods that wanted buyouts got government funding for them, while others did not. Other neighborhoods did not want buyouts at all, and instead wanted help so they could stay and rebuild in place.

In a later study, Liz and her colleagues surveyed residents across these different neighborhoods to gain insights into the long-term outcomes of these different paths. They found that people who stayed, whether out of choice or for not having received a buyout, faced higher stress levels than people who received a buyout and relocated. The study called this “the stress of staying put”.

~

Liz: And some of this higher stress was partly down to rising flood insurance rates, you know, the sense that even if people were opting to stay and rebuild their homes, not only were they maybe having to fight their insurance companies, take on a lot of debt, but they were also facing down a future where they might still wind up displaced. Could they afford to stay in those houses if flood insurance rates went up? Could they afford to sell them if they did decide to move? Would the effects of climate change, you know, make their neighborhoods increasingly uninhabitable? And so I think there were all these ways in which staying in that situation didn't necessarily equate to a recovery, even if people did manage to rebuild in place. Whereas, what I certainly noticed from talking to people who were seeking buyouts is that a number of them felt very strongly that a buyout offer was their greatest chance to achieve some sort of closure.

~

Mario: Closure was what Monique Coleman felt as she witnessed her home being torn down. She also felt relief knowing that no one else would face flooding on the same plot of land.

~

Monique: I know it sounds probably not like it was great to see your home being demolished, but for us it was like, okay, this is the finality of it all. Like, we have closed the book, this chapter is over, and this is what it looks like. It was a kind of a good feeling, too. Like, finally, this is what we needed, this is what we fought for this long, and here we are.

~

Mario: The road to this moment was not always smooth. Monique shared that it took convincing the Woodbridge town council to work with her neighborhood for the Blue Acres buyouts. She recalled that those conversations were initially adversarial, with she and her neighbors storming council meetings to have their voices heard. Eventually, the township got on board and saw Blue Acres as a way for people to get the relief they sought.

~

Monique: I think the council and the mayor saw how organized we were becoming with having our meetings, you know, spreading awareness. Especially with the state having developed this Blue Acres model for Sandy victims. So it really made a lot of sense to work together as opposed to being oppositional. Yeah, especially because we knew at that point that we were not going to get relief any other way. The Army Corps of Engineers, they said, you know, it's not economically feasible to do any kind of structural mediation here. Once that option was out the picture, we're like, this is all we have. You know, we have the Blue Acres program and it may not be the best financially for the municipality, but you have a whole community here that is, you know, is really hurting.

~

Mario: Multiple levels of government needed to be on board with Monique and her neighbors in order for retreat to happen. In the case of local governments, they have to consider the potential implications for their tax base, as well as the fact that they will have to steward the new open spaces from the buyout lots.

One place that appears to have avoided retreat is the waterfront town of Lambertville, New Jersey— a tight-knit community of about 4,000 people that’s 45 miles southwest of Woodbridge. We spoke with the town’s mayor, Andrew Nowick.

~

Andrew: I was elected in 2021 and was sworn in in January of 2022. I'm finishing my first term. I've just been re-elected for a second term, which will start on January 1st, 2025. Um, I've lived here in Hunterdon County for the last 20 years, in Lambertville for the last 13 years. My husband and I have raised our three children here and have found it a great community in which to live and work.

~

Mario: Lambertville sits on what’s been called the “other” Jersey shore, along the banks of the historic Delaware River.

Andrew was campaigning for mayor when the remnants of Hurricane Ida caused massive flooding in town. His first term as mayor was shaped by that Ida flood experience, and the town’s recovery became his administration’s central focus.

~

Andrew: It shaped everything I did. The city had suffered more than three million dollars worth of infrastructure problems. Our creeks were decimated. We lost a 44-apartment complex, you know, in the flood. A number of houses were uninhabitable for months and months. My house wasn't flooded, but a lot of my neighbor's houses were, and it was so monumental, it took me a couple of hours just to figure out what I wanted to be doing as a person that day. And I finally just went up to somebody and said, let me help you carry that out of your house. And that began my commitment to the community in terms of recovery, in terms of support, and in terms of setting future goals.

~

Mario: The flooding that happened with Ida was unprecedented. Given the widespread damage and the physical hazards posed by the town’s geography, the number of Blue Acres buyouts in Lambertville is surprising. In the four years since the storm there have been just two such buyouts.

~

Andrew: So initially there was a lot of interest in the program, and I think part of why there weren't more applicants that kind of followed through on that were, was that, people did start to rebuild, right? And, you know, these programs take a long time. So it was more than two years for the first buyout to happen on Curly Lane. So people began to reassess, I think.

~

Mario: Mayor Nowick noted that there were at least three more Blue Acres applications that were being processed at the time when we spoke. For his part, he was focusing more on various efforts to enhance the town’s capacity to manage stormwater—efforts that are within the town’s direct control.

~

Andrew: We just recently adopted the stormwater control ordinance. We have stricter requirements here to deal with impervious surface and recharge and development. We got a stormwater utility feasibility study that we did last year that's given us incredible data about what the city will need to undertake in the coming years to better manage stormwater. We have a resilience team undertaking a resilience action plan. So we're looking at all the different ways in which we can have an impact on stormwater and flooding here in town.

~

Mario: While Mayor Nowick does not see large-scale managed retreat materializing in his town in the near term, he ultimately recognizes that it’s an important option to keep open in the face of increasing flood risk.

~

Andrew: I think that we're coming to a place in communities, whether it's Lambertville or Manville or other communities across the country where managed retreats are going to be an important part of dealing with climate volatility. But I don't know that we're going to see it in a large scale way here in Lambertville anytime soon. We're certainly at risk, but three years after the most consequential flood in a generation or more, people have settled back in, people want to be here. Market rate values continue to increase. So it's hard to put forward a policy of managed retreat when people really don't want to leave, right?

~

Mario: People don’t want to leave, and market rate values continue to increase.

In the mayor’s reflections, we see that the deep attachments people have to their homes and communities and economic forces are all in the mix when it comes to managed retreat. According to Data USA, the median value of a property in Lambertville was over $530,000 in 2022. In comparison, it was $344,000 in Woodbridge and $301,000 in Manville.

Viewed one way, residents who can afford expensive properties in the first place probably have more resources and capacities to rebuild in place after a disaster. Or, viewed from another way, maybe the state finds it harder to justify funding buyouts in places where the properties are expensive compared to places where the homes are more affordable.

How do these market forces and economic realities shape managed retreat?

~

Jim: When you put money from managed retreat programs through the same market mechanisms and questions of voluntary retreat, it's going to end up like most market outcomes. Very unequal.

~

Mario: Jim Elliott is a sociologist who studies the disparities in the outcomes of managed retreat.

~

Jim: I'm a professor and chair of the sociology department here at Rice University in Houston, Texas. I'm also the co-director of a newly formed center called the Center for Coastal Futures and Adaptive Resilience. I do research on social inequalities and climate events, including long term recovery and adaptation and increasingly the question of climate relocation or mobilities.

~

Mario: Jim has been looking at how recovery unfolds after disasters, having experienced a number of them himself. He was in New Orleans when Hurricane Katrina struck. He moved to Houston, Texas in 2014, and was there when Hurricane Harvey caused massive flooding three years later.

He discovered that Harris County, where Houston is located, is a national leader in government funded buyouts. The county, which is about 1/5th the size of New Jersey, had acquired over 4,000 flood-prone properties since 1985. That’s almost quadruple the number of properties acquired by Blue Acres.

The vast majority of the Harris County buyouts are voluntary. But in 2020, the county commissioners instituted mandatory buyouts as part of a post-Hurricane Harvey recovery program. The first mandatory buyouts happened in 2021. Early reporting in the target communities shows that the new program is leading to the disintegration of Black and Latino communities.

Jim Elliott’s work has uncovered similar racial and socioeconomic inequities in the outcomes of voluntary buyouts. Those inequities are not only material but also manifest in terms of community attachment.

~

Jim: What we found is that neighborhoods that were more white and residential composition and that were more affluent in terms of median home values in that area tended to stay closer both to their homes when they retreated and to each other. So in other words, they were able to maintain attachment more than neighborhoods or people retreating from neighborhoods where they might have been more composed of people of color or lower value housing.

And so what that told us is that as this retreat is happening, more privileged communities can actually maintain their social value, and those that have been historically underserved and underprivileged have been facing more of a choice. Do I stay in place and maintain my social capital or do I leave and maintain my economic equity in my home because I can move now and take that money with me to a safer place, but basically having to sacrifice more of their social and community attachment.

~

Mario: We see this tension between economic and social values in both the drivers of retreat, as in where buyouts are implemented in the first place, as well as in its outcomes, as in what happens after. Jim says that current policies for retreat tend to prioritize economic factors and cost-benefit ratios at the expense of social capital. He says that unless something changes in the implementation of managed retreat, these programs risk replicating historical inequities.

~

Jim: What's entered into the conversation more locally is a realization that I think that's been there and suspected, but hasn't been empirically verified until some of our research, which is again, same policy, comes into the same disaster zone. But when it enters into communities that have been historically unequal in terms of access to resources and expectations of public infrastructure, that same policy can end up in very different results. And so, is that a matter of intent? Do we think FEMA is intending to do that? No, but it is a matter of consequence. So, what if we are able to provide more funds to buy out participants in lower income communities, would that allow them to find housing that's closer, might be a little bit more expensive, but if we provide more of a down payment assistance, can we sort of tip the balance so that the outcomes and the metrics become more equitable or similar.

~

Mario: As Jim and I were wrapping up our conversation, we got to talking about floods in the Philippines, the setting of this podcast’s first season. I shared how flooding was such a common life experience that people would often just clean up any debris left behind the day after and move on. Jim offered a provocative insight about choice and agency in such communities. Here’s that part of our conversation.

~

Mario: One of the researchers I've been reading a lot like lately, um, was Greg Bankoff, who writes about in the context of the Philippines, like hazard as a frequent life experience and how people have really absorbed the hazards into their everyday life ways.

Jim: And probably not by choice, right? Although people love their villages, right? So this is the tension I always see. Yeah, people are attached to the community, but they really wish it didn't flood. And sometimes you become more attached to your community because you can't imagine where else you could go. One because you haven't necessarily been a lot of different places. But the other is you don't necessarily have the resources to go actualize those choices. So a big part of this in our minds when we are studying this, it seems like people, even in the face of climate risk that's been manifest, you know, in their neighborhoods three, four times.

You don't move from something. You got to move to something. So unless there's a ‘to’, this sort of stays in place. So that's community attachment, but it's also something else. It's not necessarily having the options or being well resourced or knowledgeable about what the ‘to’ could be, right?

~

Mario: Let me just repeat that simple yet incredibly profound insight.

You don’t move from something. You have to move to something.

How do we reframe the managed retreat rhetoric and policy to focus on what communities could be moving towards? How do we empower residents of flood-prone places to imagine a suite of desirable futures, and how do we make sure they have the resources needed to turn their vision into reality?

John McCormac, the long-time mayor of Woodbridge, has done just this. Here he is in a 2019 interview with PBS’ Ivette Feliciano:

~

Ivette: Some people might look at what Woodbridge is doing and call it retreat. What do you think about that?

John: I think it's an attack. We're attacking the problem. And we're making the quality of life better for the rest of our community. By doing this, the houses that are on the fringe now are in much better shape near the zone than they were before.

~

Tom: So this is a rain garden. And it was the roadway extended all the way down.

~

Mario: Tom Flynn, the floodplain manager of Woodbridge, is taking me and producer Asela Perez-Ortiz on a walk through a former neighborhood. He’s showing us what the township has done with the land where Sandy buyout homes once stood.

~

Tom: Yeah, so there were homes here. This was, this was the extension of Claire Avenue that came down. And then… Oh, look at all the milkweed. Looks great.

~

Mario: The township has been working on restoring these former home lots to a functioning floodplain. They have planted native vegetation, including wildflowers, grasses, shrubs, and trees, all adapted to various ecological zones in the area.

It was midday, and the only other person we saw on the trail was a man walking his dog. The landscape was serene.

Tom told us earlier that his office had just ordered a batch of 12,000 more plants for this ecological restoration. He pointed out some flowers in bloom.

~

Tom: These are all black eyed susans. They're all native. They're beautiful. They were all planted, obviously.

~

Mario: His statement peels back the curtain on this landscape shaped by intentional management to maximize ecological benefits and floodplain functioning.

All of this is part of what the township calls the Woodbridge River Passage, a series of trails connecting various open spaces in town. We’re in the part of the passage that’s now known as the Watson-Crampton Blue Acres Restoration.

There are various signages along the trail. Maps pointing out how the trail connects to the rest of the passage. Pictures of wildlife that one might encounter. Signs prohibiting mowing and identifying the space as a quote “open space restoration-slash-resiliency zone”.

One sign that was posted on what appeared to be a parcel the township was still working on reads:

RESTORATION IN PROGRESS

Woodbridge Township is restoring open space in this area. This initiative will promote flood mitigation and stormwater management in an effort to increase the community's resilience against storm events. We appreciate your patience as we steward this land for the community.

There are still people here. Homes in the regulatory floodplain have been elevated. Presumably, these residents are now also seeing benefits of reduced flooding and access to nature from the land restoration.

Monique Coleman certainly hopes so.

~

Monique: Having it really be a nature, um, preserve, a sanctuary, and then also allowing the community to have spaces to enjoy nature, I think that's wonderful. That's what that land should be, right? I don't think that it really should have residential housing, those kind of structures on that property. Where it's below sea level, it's susceptible to flooding clearly. Um, and so this is the best use of that land.

~

Mario: She also thinks it would be nice to have some kind of visible marker to help people remember the community that once thrived in this place.

~

Monique: I think that would be nice as well. To incorporate that there was actually a different community, a full community here of homes at one point.

~

Mario: Next time on Carried by Water, we shift our attention to scientists witnessing and grappling with the physical drivers of retreat in real time.

~

Able: We've got a tide gauge in the boat basin, a US Geological Survey code tide gauge. And we know that on, at 2. 6 ft, water is going to start coming onto the road. That was installed in 2002. And if we plot the number of times the road is flooded, gets over 2. 6 ft, tt's increasing over time. And pretty consistently. Variable between years but increasing. So the road is a concern and could influence retreat. If we used to say, let's get together at nine o'clock in the station and we'll discuss whatever the issue is. Now we say that and then we say, has somebody checked the tide tables? Because you may not be able to get here.

~

Mario: Carried by Water is a production of Blue Lab at Princeton University. The podcast is created and hosted by me, Mario Soriano. This episode was written by me, with production support from Asela Perez-Ortiz. Additional background research by Hannah Riggins and Farah Arnaout. Voice-over for archival material by Asela Perez-Ortiz, and mixing by Hannah Riggins and Asela Perez-Ortiz.

Conversations with Nathan Jessee and Yukiko Hashida also informed this episode.

Allison Carruth is the director of Blue Lab, and Barron Bixler is the creative director.

Visit our website, bluelabmedia.org, for more information and photographs for this episode.

Until next time.

~~~END OF EP02~~~

Who manages “managed retreat”? In this episode, we examine the individual, institutional and societal dimensions of decision-making, as well as the household and community-level outcomes of relocation. We hear from Monique Coleman, who organized her neighbors to collectively advocate for buyouts after a series of floods that culminated with Superstorm Sandy, and from Tom Flynn, the flood manager overseeing the restoration of Monique’s old neighborhood into a functional floodplain. We also hear from Mayor Andrew Nowick, who voices his constituents’ desire to rebuild in place and prioritize alternative flood mitigation strategies over relocation. Experts Liz Koslov and Jim Elliott provide research-based frameworks to hold these different perspectives.

Monique Coleman watched with her family as their house in Woodbridge, New Jersey was demolished as part of the Blue Acres buyout program. The lot, now designated as permanent open space for flood mitigation purposes, has been reclaimed by nature. Photo by Mario Soriano.

Woodbridge flood manager Tom Flynn describes efforts the township has spearheaded to restore Blue Acres buyout lots into a functioning floodplain. (photo by Mario) IMG_2189.jpg - Signage for restored buyout lots. Photo by Mario Soriano.

Houses that were rebuilt in place were required to elevate the structure up to the previous flood level. Some homeowners have opted to elevate even higher. Photo by Asela Perez-Ortiz.

Andrew Nowick, mayor of Lambertville, discusses various flood mitigation initiatives he has been leading after the town suffered major damages from Hurricane Ida in 2021. Photo by Asela Perez-Ortiz.

Episode 3: Has somebody checked the tides?

Carried by Water Season 2, Episode 3: “Has Somebody Checked the Tides?”

Full Transcript

Mario: You’re swimming off the coast of the southern Jersey shore. A brief moment of sun, then you go back underwater. You’ve spent your life traversing these seas and estuaries and the rivers that feed into them. Your name is Bachelor, and you are a striped bass.

Human scientists have been following your journey through an acoustic tag and underwater listening array, pretty much like that EZ pass toll system that they use to track cars in their highways. The scientists seem surprised to see you swim more than 400 miles from Pebble Beach in New Jersey’s Great Bay, out Little Egg Inlet, and all the way up to the Saco River in Maine last year. They seem even more surprised to find you back in Great Bay a year later.

Why are they surprised though? The Great Bay estuary is a special place, so of course you would come back.

From Princeton University’s Blue Lab, this is Carried by Water. I’m Mario Soriano.

Episode 3. Has somebody checked the tides?

Situated right on the edge of Great Bay, at the junction where the Mullica River meets the Atlantic Ocean, the Rutgers University Marine Field Station serves as a home base for scientists studying fishes like Bachelor the striped bass and other marine life.

I visited the field station with my students Hannah and Farah.

~

Mario: Hi, I’m Mario.

Lisa: Oh, Mario. Hi. Great to meet you.

Mario: It's great to meet you.

Lisa: Welcome, welcome.

Hannah: Nice to meet you. I'm Hannah.

Lisa: Hi, Hannah.

Farah: Hi, nice to meet you. I'm Farah.

Lisa: Farah?

Farah: Yeah.

Lisa: Oh, great. Welcome to the field station.

Farah: Thank you.

Lisa: Is this your whole group?

Farah: Yeah.

Lisa: And I'm so glad the weather held out because it's, it's beautiful but messy out here. Messy weather. Yeah. Come on in.

~

Mario: We were given a tour by Lisa Auermuller, a researcher at Rutgers University.

~

Lisa: My role is to be like a bridge between science, knowledge, data that we're collecting along the coast and translating or communicating that information to the decision makers on the ground.

~

Mario: The marine field station’s physical buildings were once what constituted the Coast Guard’s Station 119 at Little Egg Inlet. The iconic red roofs and white walls are emblematic of the so-called “Roosevelt-era” Coast Guard stations built in the 1930’s. These Colonial Revival-style facilities feature exterior porches, boathouses, and a cupola, which is where Lisa took us first.

~

Lisa: Okay, so let me go up first and then I'll open the hatch and then you all can come up.

~

Mario: The cupola, with its large windows on all sides, offered a wide open, three-hundred-sixty degree view of the surrounding land and seascape.

~

Lisa: So we are in the cupola of the Rutgers University in Rain Field Station, which is located in Tuckerton, New Jersey. We are very far south in Ocean County, New Jersey. We are on a salt marsh peninsula, which you're gonna be able to get a very good vantage point of visually. From here, you can see very clearly, Atlantic City in the background. Um, and it's a clear enough day. We can see it pretty well. Um, we are right here at the inlet for the Great Bay. And then this way, behind us, is the back bay portion of Little Egg Harbor and Tuckerton. So you can see all that from this vantage point.

~

Mario: All around us, water and land wove through each other to form this rich estuary and marsh. The only other man-made structure within a mile or so was a rusty menhaden fish factory that was abandoned back in the 70’s, when the local menhaden populations plummeted due to overfishing. A diverse suite of creatures like striped bass, river herring, horseshoe crabs, various birds, mammals and insects, can be found residing within this dynamic ecosystem throughout the year.

~

Lisa: I actually see a terrapin in the boat basin right now by one of the docks. Do you see? It's sticking its head out.

~

Mario: There, casually chilling near one of the station’s research vessels was a diamondback terrapin. Terrapins are a kind of small turtles that are native to the brackish waters of the US East and Gulf Coasts. Diamond-like patterns mark its shell, with each terrapin having unique markings. The IUCN Red List identifies diamondback terrapins as Vulnerable.

Part of the research at the field station is to observe and track the lives of the marine creatures in the surrounding ecosystem.

~

Ken: Fish swim under my office on high tide.

~

Mario: This is Ken Able.

~

Ken: I am a retired professor, i.e., emeritus professor, in the Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences at Rutgers University, and I'm the past director of the Rutgers University Marine Field Station. I've been here for about 38 years after teaching on main campus for about 9 years.

~

Mario: He has spent almost his entire career here at the field station.

~

Ken: So because of our location, we're doing long term studies, sampling with traps in our boat basin, sampling with trawls throughout the salinity range of the estuary, and sampling larval fishes coming in through the inlet. All those studies began in the 1990s. And we've maintained them even through COVID. We've been able to maintain these studies and they are insightful.

~

Mario: Rutgers acquired the old Station 119 in 1972. Ken arrived at the Marine Field Station in 1986 and was appointed as its director the following year. He remained the station director until his retirement in 2019. Throughout this time, he mentored more than fifty graduate students and postdocs, as well as countless undergrads and student volunteers. He’s still quite active at the station, and he says that these days he’s focusing on translating his almost four decades of scientific inquiry into knowledge that the public can understand. It’s very evident that he holds the station dear and considers it to be a continuing source of inspiration.

~

Ken: My motivation comes from just my interest in these systems, especially watery systems. They're so changeable on a day-to-day basis with the tides, and so we get to have a front row seat for understanding what those changes mean. We've learned an immense amount about a lot of fishes and crabs and even those that, uh, that are economically important. We've contributed to, uh, their, a better understanding of their life history. Things that just weren't known. Uh, people have written about what they call the ecology of place and how places can be critically important because they foster long-term studies and a whole host of other reasons. This is a place that deserves attention and I want to make sure that it receives that attention.

~

“I may be wrong about the Mullica River. I don’t think I am. To me, the Mullica is the most wonderful of the unrecognized rivers of America.”

- Henry Charlton Beck, Jersey Genesis: The Story of the Mullica River, January 1945

Mario: This place, where the Mullica River meets the Atlantic Ocean, is unique in that it is the cleanest estuary in the entire US east coast. Very few people live within the watershed, which is evident in that it is home to many of South Jersey’s so-called ghost towns, places long abandoned since industries like lumber and grist mills and shipbuilding died over a hundred years ago.

Federal and state protections include the Pinelands National Reserve, the Wharton and Bass State Forest, the Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, and the Jacques Cousteau National Estuarine Research Reserve. Researchers often use the pristine estuary’s conditions as a baseline or reference for comparison with more heavily developed sites.

~

Lisa: Because of that lack of development due to the Pinelands regulations compared to other much more developed parts of New Jersey, this area is considered almost like a reference in some ways to then compare other more impacted areas. So we're perfectly positioned at the inlet to be able to look up that Mullica River gradient and understand fish migration and invertebrates and water quality and how all of that interacts in this very, very low impacted system.

~

Mario: One long-running endeavor in the station is the collection of larval fish samples coming into the estuary from the Atlantic Ocean every high tide. This has been going on for the last 38 years, giving a very detailed look into how the fauna have changed over time.

~

Ken: We've been sampling them every week on night flood tides, because we want Atlantic Ocean water that's coming in through the inlet and carrying larval fishes with it. They spawn in the ocean, but they use the estuary as a nursery, a place to grow up. High tide can be at nine at night, can be at midnight, could be at three in the morning. It doesn't matter. Somebody here is out there on every night flood tide once a week to do that sample.

Lisa: So it is someone's job to take what comes out of these nets, and literally pick through and identify the species of each of the organisms they collect in those ichthyoplankton net toes and, um, I'm glad that's not my job. But, uh, somebody sits here and does that.

Ken: So it is an incredible amount of effort. We have all kinds of people. We have volunteers. And I love the volunteers who are involved because I consider them ambassadors to our local community.

~

Mario: This long term dataset, carefully assembled through the combined efforts of volunteers and scientists, sheds light on the lives of non-human residents of the estuary and serves as a bellwether for the impacts of a changing climate.

~

Ken: The larval time series have shown us quite clearly that the fauna is changing, and this is closely correlated with increasing water temperatures.

Lisa: We are not the only research lab that does this kind of work, although I think we are the longest one. Other labs up and down the east coast also do this, so we can share data across those labs to see if we're seeing less of something, but up north they're starting to see more of it, then we know that's part of the larger picture of the story.

Ken: We're seeing more southern species and fewer northern species, and that is happening over and over again in recent years. So much so that one species, the Atlantic croaker, that wasn't here when we first started the time series, is now the basis for a commercial fishery. So not only are rare individuals showing up, but enough individuals that they're the basis, the adults are a basis for a fishery. And all of our time series say the same thing. The fauna is changing in response to climate change.

~

Mario: Climate change is also affecting the scientists’ ability to do their work at the station. Back in the cupola, Lisa pointed out a very visual marker of this reality.

~

Lisa: See those concrete pads that are out there? There's three of them. That used to be a meteorological tower. We have had massive erosion of the edge along the side of the peninsula and the land that used to hold that meteorological tower had eroded away. And so it was in risk of falling in, so they preemptively took it down. But as you can see, we've lost a tremendous amount of edge there. And the edge moves closer and closer to the building all the time. So we ourselves are fully aware of what that exposure means and what risk that brings to the operations of the station. And we are even starting to view the station itself as almost like a research node to track and analyze and equip sensors and other monitoring protocols so that we can actually live and understand what's happening with the erosion and the edge as we are kind of ourselves dealing with it.

~

Mario: More extreme storms and surges are also a threat. While the station buildings themselves have proven quite resilient, operations can still be significantly hampered.

~

Ken: We were in here the day after Sandy came through, but it was difficult and the road near the first bridge from town was all torn up and the police closed it down. We convinced them that we'd be okay. We could get in, and they let us in. So we saw the damage right away. And fortunately when they built this in the 1930s, they built them extremely well with massive beams and so on.

Lisa: Underneath the field station was a bunch of our plumbing and electrical wiring that a lot of that got washed out. They had to redo the whole wastewater system out here. It took multiple years to get that back up to snuff. Um, many of the floating docks were destroyed. They're actually still working on dock repairs 12 years later. Um, one of the boats ended up washed away inland to part of a marsh that you would never imagine this boat could have gotten washed into. And the building itself inside wasn't damaged, but some of the ways that we function out here really took quite a hit.

~

Mario: Superstorm Sandy also illustrated the vulnerability of the only road with access to the field station. This road is called Great Bay Boulevard and is locally known as The Seven Bridges Road. Only five bridges actually exist because the last two were never built. The larval fish sampling we mentioned earlier happens in the bridge closest to the field station. Today, flooding of the road is becoming a regular occurrence that the scientists working at the station have to deal with.

~

Lisa: Multiple times a month now the tide is at a high enough point that the road is inundated at certain locations. Not great for your car. Uh, not great for traveling. So we have all, as staff here, adapted our operations to have a tide alert app on our phone when we, it breaches a certain threshold that we preset in and that alert goes off. You know, you have a limited amount of time to either not come in or get out if you don't wanna get stuck out here.

Ken: We've got a tide gauge in the boat basin, a US Geological survey code, tide gauge. And we know that at 2.6 ft, water is going to start coming onto the road. That was installed in 2002. And if we plot the number of times the road is flooded, gets over 2.6 ft, it's increasing over time. And pretty consistently. Variable between years but increasing. We used to say, let's get together at nine o'clock at the station and we'll discuss whatever the issue is. Well, now we say that and then we say, well, has somebody checked the tide tables? Because you may not be able to get here.

~

Mario: As the scientists are witnessing these impacts firsthand, they are also grappling with the question of what to do. Ken wrote about this in one chapter of his book, Beneath the Surface. I asked him to read an excerpt.

~

Ken: Over the next several decades with continued sea level rise and potentially more frequent storms, we anticipate further accommodation will be necessary. Supporting evidence for these kinds of changes are the consensus of climate scientists around the world, along the East Coast, and our own observations in the Mullica Valley. Objectively, then, we need to develop plans for continued accommodation, protection where possible, and retreat where or when necessary. Given our ideal location for place-based research on the effects of climate change and sea level rise, we anticipate continued and increased monitoring and research on these issues, despite the inconveniences.

~

Mario: I asked him to tell me more about his thoughts on retreat.

~

Ken: At the current rate of sea level rise, we will probably have to retreat from this location. The problem is knowing when. It's not gonna happen in my lifetime. I don't think it's gonna happen in the lifetime of many of the other people working here, but we really don't know. These stations are movable. There are incredible numbers of people who have moved their houses further inland, higher elevations, and so on, and maybe that is the future of this facility.

~

Mario: Lisa and Ken say there are many factors to consider when planning for the future of the station.

~

Lisa: If I put on my hat as a person who often is trying to translate information and present options for decision makers, things that I think need to be thought about are: Um, what is another location when we are having so much flooding on the road that we're not able to get out here all the time? Working from home is currently an option. But is there another location we should be looking at? Another physical location further inland that we should be looking at as a secondary site, which might eventually become a primary site. I mean, how many times a week does it have to flood before we make a decision that it's not viable to continue going out there?

Ken: If we had to retreat from this location, we would lose a whole series of different kinds of observations. These stretch from hourly observations during a storm, for example. Daily observations when you see, oh, why are the marsh pools getting bigger than they used to be? There are many seat of the pants observations that we make that are incredibly insightful in guiding how we educate people, how we do our research. And that seat of the pants understanding is one of the major things that we would lose if we had to change locations. I don't even like to entertain the idea because it detracts from our ability. This location provides for incredible insights. And I just had one now, while I was talking. An osprey landed on one of the buoys out there, and reminded me that someone just came by and they want our fish data to help understand the apparent decline in ospreys. That's the kind of thing that pops into your head, into my head, when I'm driving down the road or I'm sitting here and I'm staring out the window. But yeah, it's those, those insights. That's what would be lost. That's what is so important.

~

Mario: Thinking now not just about the station but managed retreat from the coast more broadly, Lisa says that what you know and what you feel can often be at odds with each other.

~