Season 2

An Original Audio Story Series Led by Nate Otjen + Jessica Ng

Season 2: McDermitt Caldera, Nevada

You can find Mining for the Climate on on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, iHeartRadio and PlayerFM.

Season 2 brings listeners to the McDermitt Caldera, a desert region that has recently become the epicenter of US lithium mining. Far from being a barren landscape, the caldera is home to many people, along with numerous species of animals and plants. In this season, we talk with local experts who are concerned about impacts from Lithium Nevada’s 6,000-acre Thacker Pass Lithium Mine and several other mining projects that are currently underway. While lithium extraction promises to be a “new frontier” for ranching and mining communities like Orovada that haven’t experienced this activity before, mining in the region is a long and complex issue, one that dates to the founding of Nevada and one that Indigenous communities like the Fort McDermitt Indian Reservation have long contended against.

Credits

Created by Nate Otjen and Jessica Ng with research, writing and production support from Chris Bao and Jose Santacruz.

Mining for the Climate is a production of Blue Lab with support from Princeton University. For their support and expertise, we also thank, at Princeton, High Meadows Environmental Institute, Princeton Humanities Council and Princeton Office of the Dean for Research.

Copyright 2025 Nate Otjen, Jessica Ng and Blue Lab.

Episode 1: Energy Colony

Mining for the Climate Season 2, Episode 1: “Energy Colony”

Full Transcript

[00:00:00]

Jose: It's June 27, 2023 in Pasadena, California, outside the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Dozens of Indigenous activists and their supporters have gathered in prayer and protest of the Thacker Pass Lithium Mine. Some have traveled hundreds of miles to protect their homelands in Northern Nevada. Inside the courthouse, a panel of judges will decide the fate of the [00:01:00] mine.

Jessica: For two years, Lithium Nevada, a subsidiary of the mining corporation Lithium Americas, has been working to develop a mine on Thacker Pass, a site located on the southern end of the McDermitt Caldera in Nevada's Humboldt County. The company first filed a plan of operations in 2019 with the Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, the agency responsible for administering U. S. public lands. In early 2021, the BLM issued a formal decision that constituted federal approval of the mine.

In the years since, the federal government and mining and green energy companies have held up Thacker Pass as an exemplary project. The public is told that it'll create jobs, provide a steady supply of domestic lithium and help the country address climate change.

The surge in interest in lithium reflects a national security strategy, a larger effort to secure so-called “critical minerals” and “energy market competitiveness” [00:02:00] against countries like China. During his four years in office, President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and the Chips and Science Act — bills that included stipulations to increase investments in green technology, and particularly lithium batteries.

Jose: Lithium mining receives support because it's portrayed as a necessary part of the energy transition. As climate action frameworks like the Green New Deal and carbon neutrality make their way into mainstream discourse and international climate agreements stress rapid decarbonization, opening new mines has come to be seen as a climate solution. Perhaps worse, those who stand in the way or question the growing status quo are increasingly labeled rabble rousers and climate deniers.

Welcome back to Mining for the Climate. My name is Jose Santacruz.

Jessica: My name is Jessica Ng.

Jose: And we're your hosts for this first episode.

Jessica: Thacker Pass, which contains the [00:03:00] largest known lithium deposits in the United States, promises to produce around 40,000 tons of lithium carbonate annually, all of which would be used in electric vehicles produced by General Motors. Lithium Nevada estimates that the mine could support the production of batteries for up to 800,000 electric vehicles annually.

Chris Henry: If we're going to have electric vehicles, we're going to need a lot of lithium. And if we don't have lithium and other things, we can't make that energy transition. You know, we're doing something that creates a modest disturbance to accomplish a much greater good.

Jessica: That's Chris Henry, a retired geologist with the University of Nevada and the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology. His perspective is one shared by many.

Jose: Others have come to see the Thacker Pass mine not as a beacon of opportunity, but as a gaping hole in the ground that exposes injustices within the energy transition. For them, Thacker Pass signals a harbinger of cascading [00:04:00] consequences. Here's Ian Bigley of the nonprofit Earthworks.

Ian: You know we were being sold single occupancy electric vehicles as the solution. “Everybody gets a sexy electric truck, you stop feeling guilt, climate change is done.” However, that's bypassing some of the real solutions that we need that would reduce demand. As we're doing this transition, we have to make sure to do it as good as possible and not just in a way that's the most profitable or the most expedient.

Jose: Initial opposition to Thacker Pass Mine was swift and strong, with conservationists, ranchers, and Indigenous tribes seeking to halt its construction. Some argued that the environmental impact assessments were rushed and that the mine would threaten the area’s flora and fauna, many of which are endemic and endangered. Others pointed to the cultural importance of the land for tribal groups, particularly the McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone, and condemned the process for excluding [00:05:00] consultation, and the mine for its potential destruction of their homelands and sacred sites.

Jessica: Still others, like local resident Susan Frey and the ranching community of Orovada, have emphasized how rural communities were strategically disenfranchised in the wake of new mining operations.

Susan: I think that's been one of the hardest things to accept as a community that we don't get a vote on what happens around here as far as mines coming in, because there are other mines that are currently prospecting and drilling and this whole area could potentially become one big lithium mine.

People don't want that here but we don't have any way to stop it, and nobody ever seems to stop at these small communities that are directly affected and get the feedback from the community on what we might see as solutions for problems that [00:06:00] they're bringing us. Because we didn't have these problems until the mine came in.

Jose: A number of lawsuits were filed over the next several years. Peaceful protest occurred at or near the proposed mine, led by Indigenous and environmental activists. The opposition quickly drew the attention of mainstream media, which told the story of political polarization and irresolvable conflict. Many people supported the mine, including many Nevadans, and many opposed it. Not only communities within Nevada, but also allies beyond.

Jessica: The coalition of those opposing the mine hoped it could be stopped, but on July 17th, 2023, a last-ditch effort to halt the mine was rejected by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in Pasadena, which agreed with a prior court decision to let construction proceed. Since then, media attention has dwindled as mine construction moves forward.

Jose: Even as some are disheartened, many are ready to take on the next fight. How the [00:07:00] rush to mine the largest lithium deposit in the US unfolds over the coming years could hold important lessons for other critical mineral projects as well as opposition to them. This past summer, the US Secretary of Energy, Jennifer Granholm, visited Reno to talk about Nevada's role in the renewable energy sector.

Secretary Granholm: We just stood by while our economic competitors came and ate us for lunch. They were so successful that in the 2000s, 60,000 factories left America.

Jessica: Last season on Mining for the Climate, we explored the origins and local conflicts around a proposed lithium mine in Gaston County, North Carolina. That story investigated the tactics used by Piedmont Lithium to amass land, highlighting the varied responses and views of community members, and addressed the complexities of mine permitting as well as the potential ecological consequences of this particular mine.

We ended that season with the [00:08:00] open question of whether the mine would receive approval. In May 2024, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality issued a mining permit for Piedmont Lithium. The Gaston County Board of Commissioners will make the final determination about whether the land will be rezoned for mining.

Jose: This season of Mining for the Climate takes listeners to the other side of the country, in a different historical and legal context, with different actors and stakes. For starters, the lithium mine at Thacker Pass is already under construction.

Despite the specific dimensions of each mining project, we continue to ask key questions about the role of mining in the green energy transition. What causes a mind to be built? How do narratives of urgency overshadow opposition? What and who are displaced or erased for a mine? And whose homes, lands, and waters are being sacrificed for a so-called better future?

Autumn: [Introducing herself in Paiute.] [00:09:00] My name is Autumn Harry. I'm a member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute tribe here in northern Nevada, and I am both Paiute and Navajo.

Jose: Autumn has lived in Pyramid Lake her entire life and a few years ago became the first Paiute woman licensed to guide fly fishing trips on the lake. At the time we met her, she had recently finished her master's degree in geography at the University of Nevada, Reno and was working on a mural for the school.

For her, construction of the lithium mine relies on the idea of sacrificing remote places and less-visible communities in the name of progress.

Autumn: When I think about places like Peehee Mu’huh, it's a lot further of a drive from Reno or Las Vegas or Elko. I think because it's more remote, people haven't had the opportunity to even visit or be on that land. And it's really easy for people who have the power to make these decisions, whether it's in the [00:10:00] court or within policy, to just say, “Oh, no one goes out there. Nobody knows about that. Let's build a lithium mine.”

Jessica: Peehee Mu’huh is the Paiute name for Thacker Pass. It translates to “Rotten Moon,” which refers to an intertribal massacre between the Paiute and Pitt River tribes. A second massacre happened here in 1865 when the First Nevada Cavalry of the U. S. Army murdered 30 Paiute people. Because of this painful history, the land is sacred to tribal peoples, some of whom are descendants of those killed. Here is Dorece Sam, a descendant of Ox Sam, the only Paiute to have survived the 1865 massacre by the Nevada Cavalry, explaining the name's meaning.

Dorece: It's kind of shaped in a moon. It's like moon shaped. The massacre that first happened, it was undocumented, but it happened from a different tribe from the Pitt River. The men folks went out to hunt. And the families were behind. The Pitt River came [00:11:00] in and massacred the families.

So it was like a couple of days, and by the time they got back, it had the rotten smell. And, because of the crescent shape of the moon that's how it got its name, Peehee Mu’huh. Rotten moon.

Jose: To Dorece, Autumn, and many other Paiute and Shoshone people who met with us and shared their stories, what's happening at Thacker Pass is a continuation of a much longer colonial history. The mining project is not isolated, but is part of a long pattern of dispossession and harm.

Autumn: I think that's the pattern that we're seeing within the Great Basin. Indigenous peoples are thrown to the side. For people who are making those decisions, that connection to the land doesn't matter to them.

Jessica: A 2021 report found that the majority of lithium reserves were located within 35 miles of reservation land. Considering that lands with cultural importance often extend beyond reservations, it's no understatement to say that lithium mines could be one of the most [00:12:00] consequential forms of resource extraction to impact Indigenous groups in the coming decades.

Jose: The federal governments under the Biden Administration pledged that clean energy and related investments will not redouble historical environmental injustice, committing that “40 percent of the overall benefits of certain federal climate and clean energy, affordable and sustainable housing and other investments flow to disadvantaged communities that are marginalized by underinvestment and overburdened by pollution.” But for some community members living near the Nevada mine, they're being asked to bear 100 percent of the impacts of the energy transition.

Jessica: While many of us can ignore mining in other countries or other states, those who live near Thacker Pass will have a much harder time going about their lives without disturbance.

Paul: That dialogue has been around since, you know, really, the origins of [00:13:00] western expansion. “We need to develop minerals in order to develop as a nation, in order to become strategic, and maintain our position in the world, we must have access to these minerals.” And one of the things that's, I think, quite convenient in that argument is that mineral districts are often located away from seats of power. You know, they're out in the boonies. They're out in areas that are isolated for non-Native people, areas that are foreign, or areas that are just desert.

Jessica: That was Paul White, Professor of Geography at the University of Nevada, Reno.

Those who live and work in the McDermitt Caldera are growing increasingly concerned that their future holds not just the Thacker Pass mine, but a network of lithium mines stretching from northern Nevada to southern Oregon.

Jose: The concerns are far from unfounded. If you look at a map of lithium claims in the McDermitt Caldera, you'll see that the majority of land has already been [00:14:00] surveyed, parceled, and claimed. In the north, companies like Jindalee, FMS and Aurora hold mining claims. And in the east, there's Livent and FMS, and, to the south and west, Lithium America holds lithium claims to huge tracts of land.

Jessica: For those who are worried about or organizing against Thacker Pass, the danger isn't a single mine. It's the risk of the entire region becoming an energy colony for lithium batteries. For many, it feels like the approval of Thacker Pass has paved the way for future extraction throughout the lithium-rich caldera.

Jose: We're already seeing this with the widespread implementation of fast-track permitting, a process that started with the Thacker Pass Mine initiated by the first Trump Administration, and continuing under the Biden Administration. So far, billions of dollars have been poured into that capacity with more to come. In late December of 2024, on the eve of the second Trump Administration, Lithium Nevada released plans to significantly expand the mining [00:15:00] site and its operations. It remains to be seen what an anti-electric vehicle, but pro-mining government means for the Thacker Pass Mine. But it seems likely that federal and industry support will continue no matter the costs.

Jessica: General Motors has promised $665 million, and the Department of Energy has agreed to a conditional $2.26 billion loan for the construction of a processing plant, the largest federal investment in lithium extraction to date.

John: From our point of view, we see the frontline communities, they're the ones that are taking the hit. And, that's my question to a lot of, sort of climate hawks, is that, what are you willing to change? What you're asking for are communities, especially Indigenous communities, to lose a chunk of their culture forever. What's your sacrifice? Different type of toothpaste?

Jose: Season 2 of Mining for the Climate will take a hard look at what's happening at the McDermitt [00:16:00] Caldera. In many ways, this region is setting the stage for future critical mineral development and opposition in the United States. Is the future an energy colony or are there other paths forward that do not create new sacrifice zones and that advance climate justice?

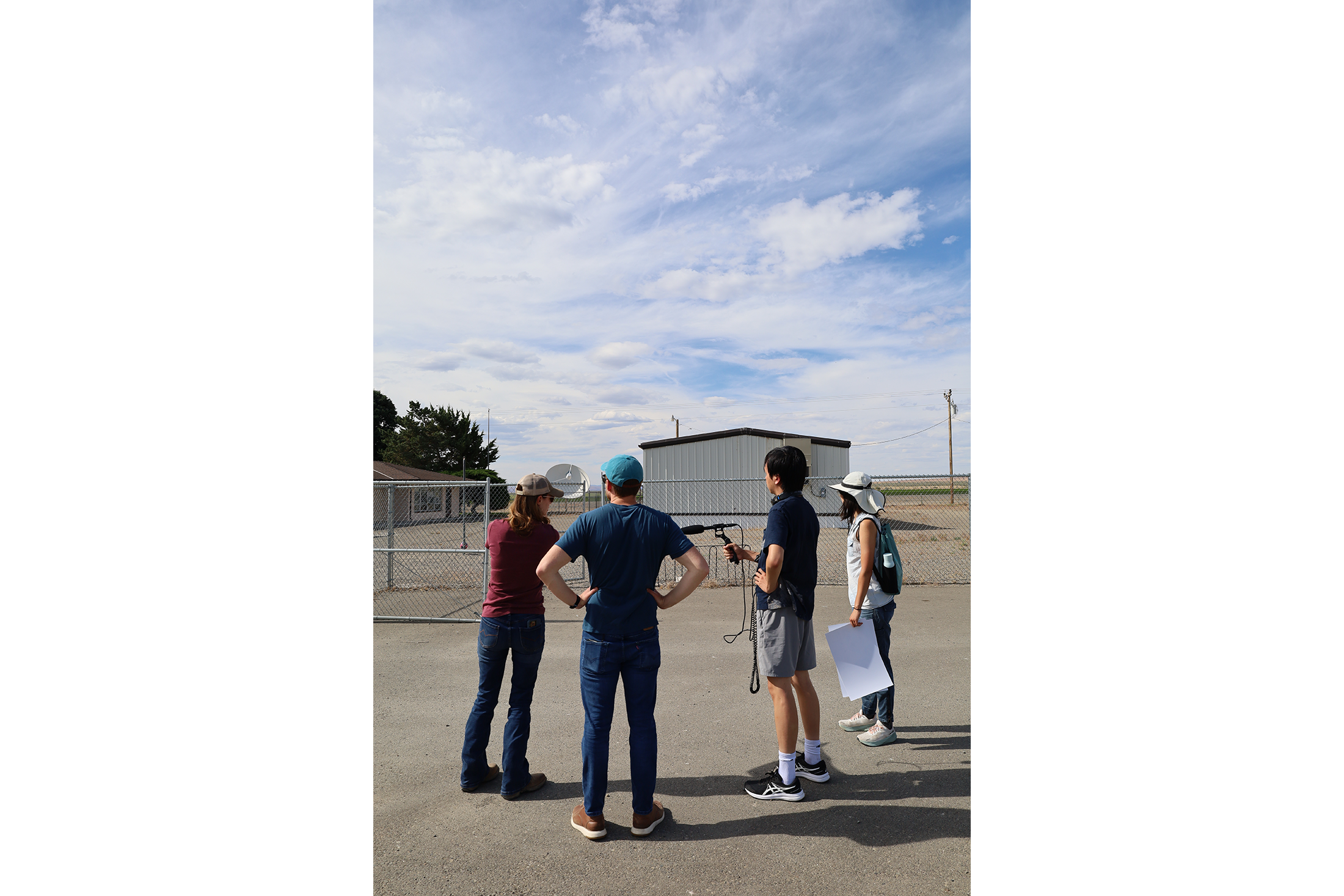

Jose: This season consists of Nate Otjen, Jessica Ng, Chris Bao, and Jose Santacruz.

Nate: My name is Nate. You heard from me on the first season. I'm an Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at Ramapo College and was previously a Postdoctoral Researcher at Princeton. I'm concerned about who benefits and who suffers from the energy transition. Again and again we see that the most vulnerable communities are forced to bear the brunt of mining, even as they rarely benefit from it.

Jessica: I'm Jessica Ng, a Postdoctoral Researcher at Princeton. I've been working alongside communities and organizations resisting lithium mining for the past seven years. I visited the prayer and protest camp 2021.

Chris: I'm Christopher Bao, and I'm a sophomore at Princeton. I'm interested in the narratives that are told and the narratives that are missed in the energy transition as many start to recognize the necessity of change, whose voices are heard and amplified, and whose are overlooked or ignored. Understanding people and their stories is critical for making better policies and better futures.

Jose: And I'm Jose Santacruz, an undergraduate student at Princeton studying architecture. I'm captivated by people's [00:18:00] love for place and how a place can become a home. Unfortunately, people's sense of place is often ignored when discussing the energy transition. When designing solutions, we must take this into account.

Nate: Mining for the Climate is a co-creation of Nate Otjen, Jessica Ng, and Juan Manuel Rubio. And it's a production of Blue Lab at Princeton University.

This episode of Mining for the Climate was written by Christopher Bao and Nate Otjen; produced by Nate Otjen; and edited by Jessica Ng and Nate Otjen.

Our research and production team includes: Christopher Bao, Jose Santa Cruz, Jessica Ng, and Nate Otjen.

Sound design is by Gianna Imparato. Music for this episode was by Pixabay. Find it at pixabay.com.

Mining for the Climate was made possible by funding from Blue Lab, the High Meadows Environmental Institute, the Humanities Council, and the Office of the Dean for Research at Princeton University. Ramapo College generously provided faculty research funding.

We would like to express our gratitude to the following people for their generosity and kindness: John Hadder, Ian Bigley, Susan Frey, Day Hinkey, Myron Smart, Justina Paradise, [00:31:00] Gary McKinney, Katie Fite, Dorece Sam, Edward Bartell, Kassandra Lisenbee, Terry Crawforth, Autumn Harry, Chanda Callao, Daniel Rothberg, Ryan Houston, Paul White, Kate Berry, Eric Nystrom, Simon Jolette, Ka’ila Ferrell Smith, Josh Dini, Carolina Muñoz-Saez, Ehsan Vahidi, Paul Ruprecht, Rick Eichstaedt, Chrissy Klenky, Nick Erruty, Patrick Donnelly, Philip Ruprecht, Will Folk, Glenn Miller, Mike Visher, Rich Stone, and Dave Mendiola.

At Blue Lab, we especially thank last season's Mining for the Climate team: Juan Rubio, Grace Wang, Max Widmann, and Alex Norbrook, along with the lab’s leadership, Allison Carruth and Barron Bixler and fellow members Jamie Collins, Mario Soriano, and Asela Perez Ortiz.

And at the High Meadows Environmental Institute, we thank Emily Ahmetaj, [00:32:00] Stacey Christian, Kathy Hackett, Nathan Jesse, Ryan Juskus, Zack Kaado, Heidi Mihelich, and Laura Matecha.

Nevada has a long history of mining. In the last decade, the state has positioned itself as the leading producer of lithium in the United States. This episode looks at how the recent approval of the Thacker Pass Lithium Mine in northern Nevada foreshadows larger efforts to turn the region into what some activists and scholars term an energy colony.

Episode Credits

- Written by Christopher Bao and Nate Otjen

- Hosted by Jessica Ng and Jose Santacruz

- Sound design by Gianna Imparato

- Research and production team: Nate Otjen, Jessica Ng, Christopher Bao, and Jose Santacruz

- Music by Pixabay (www.pixabay.com)

Audio Clip Credits

- US Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm Talks Industrial Strategy in Reno, 2NewsNevada, 2024

Copyright 2025 Nate Otjen, Jessica Ng and Blue Lab (bluelabmedia.org). All rights reserved.

Tribal community members pray with song and drums as their case is heard in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in Pasadena, CA, in June 2023. Photo by Juan Rubio.

Billboard by People of Red Mountain proclaiming “Life Over Lithium.” Taken south of Orovada in June 2023. Photo by Alex Norbrook.

View of Camp Peehee Mu’huh, a prayer and protest camp of Paiute Shoshone tribal members and allies, in July 2021. Photo by Jessica Ng.

Episode 2: Caldera as Home

Mining for the Climate Season 2, Episode 2: “Caldera as Home”

Full Transcript

Day: You see our homelands, Red Mountain, way over there in the yonder. See it? It's got a cloud standing on top. See way back there?

Myron: When I was little, my dad used to come out here quite a bit. Used to come out here and get the cottonwood. And they share that with people for ceremonies and things. I used to talk about all of the sacred sites out here.

Justina: We care for our Mother Earth because it gives us life. If it wasn't for her, you know we wouldn't be alive. And digging her up and looking for lithium, gold, silver, mercury, whatever, those are the main parts of her survival.

Chris: Welcome back to Mining for the Climate. In the previous episode, we introduced the major issues and key players surrounding the Thacker Pass Lithium Mine, which you just heard Day Hinkey and Justina Paradise invoke as we stood with them in the McDermitt Caldera last summer. In this episode, we will turn the focus to this landscape, the place in which the mine is already underway.

Who currently inhabits the caldera, and who stands to lose from the construction of the mine?

Autumn Harry, an artist, fly fishing guide, and member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute tribe, told us how her way of viewing the land is often at odds with predominant views of desert environments like this part of northern Nevada.

Autumn: This is a desert environment and Lake Tahoe is just over the mountains there. I think growing up, so many people have always fixated on Lake Tahoe and how beautiful it is, and the greenery. But then when they come to the desert, within settler colonial ideology, people don't see it as beautiful. These are our homelands; our people have lived in the desert for thousands and thousands of years and have adapted to the desert. And so I think of it as being so beautiful and special.

There's so much value in the desert for our people, and I think sometimes people have a hard time seeing that, and that's why we do see so much mining and devastation coming to our homelands.

Chris: Outsiders who are not intimately connected to the land have long viewed the deserts of the American West as barren and empty. But humans and other beings have existed with the land since time immemorial. In this episode, we hand the story off to the people who have deep connections with the place where Thacker Pass sits and who understand, on a personal level, what it would mean to lose those attachments.

Like Autumn, some of the folks we will hear from are descendants of the Paiute and Shoshone. Others are more recent to the area, settlers who are conservationists or ranchers.

Despite their differences and sometimes conflicting interests, the people whose voices you'll hear all speak to the complex environment of the caldera and the webs of relationships that sustain animals, plants, and the land.

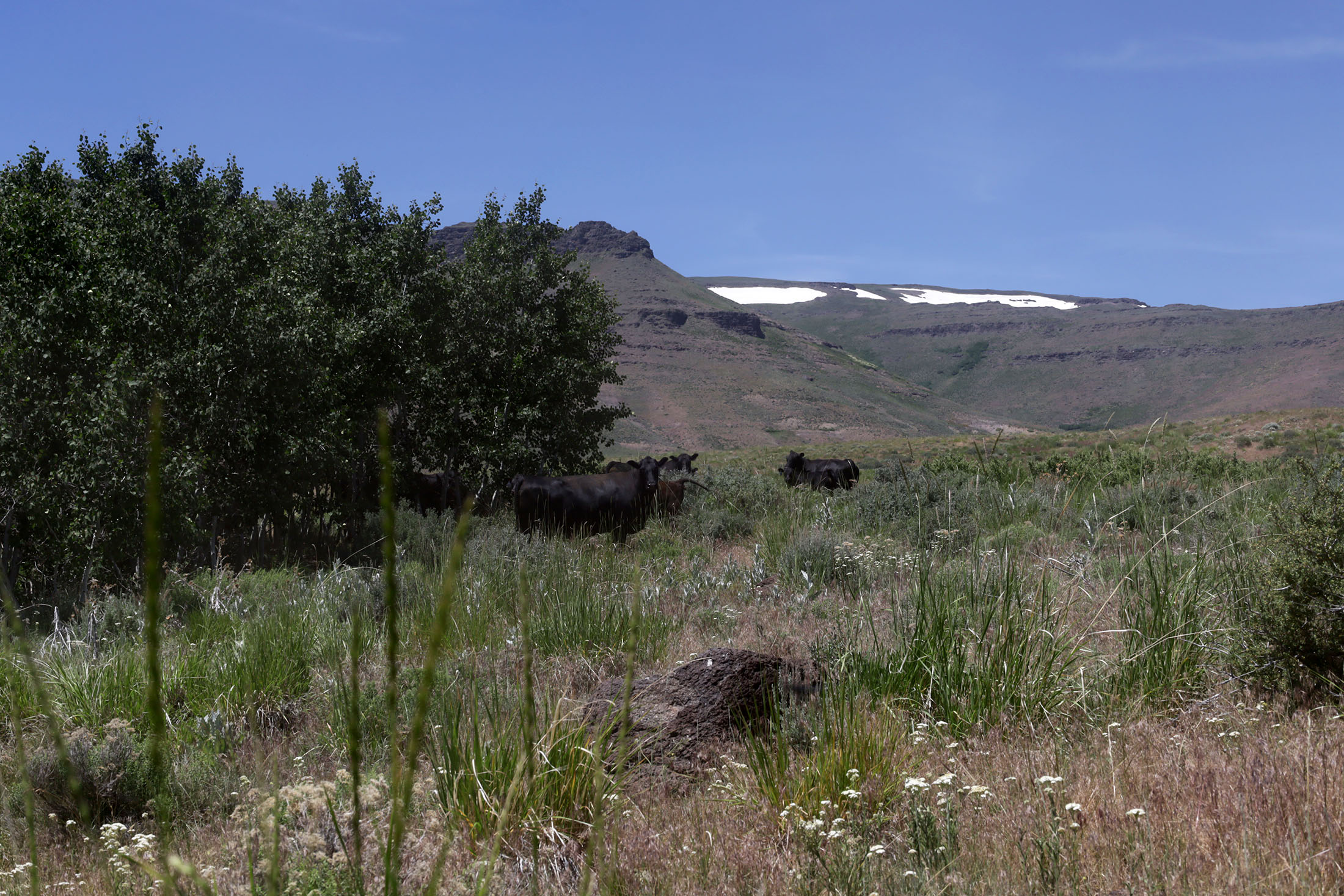

One of the first features that stands out when driving into the McDermitt Caldera is the openness of the landscape. The ground unfolds in all directions, undulating and rising as it moves toward the horizon. The towering mountains give the place a feeling of drama and otherworldliness. Desert hues of brown and red dominate the color palette, but there are also deep greens and blues that reflect an abundance of life.

Take the sagebrush that dot the area. A silvery green color, these plants seem to extend endlessly throughout the caldera.

Katie: This is Mountain Big Sagebrush. It's a different subspecies of sagebrush than the Wyoming Sagebrush. There's a couple different species of the shorter-statured sagebrush. So sagebrush is not just sagebrush.

Chris: That's Katie Fite, the Public Lands Director with Wildlands Defense, an environmental group that protects wildlands and wildlife, especially sage grouse, in the western United States.

A resident of Idaho, she is cheerful and energetic, frequently jumping from one topic to another as she speaks. Katie explains that sagebrush, as the dominant plant in much of the Great Basin, provides food and habitat for many species. An intact sagebrush landscape is particularly important to regional birds and rabbits that would otherwise be highly vulnerable to predators.

Katie: If you're a species that nests in sagebrush, you want this unbroken, unfragmented landscape, not like a road, road, road, because predators work the edges essentially, coyotes trotting down the road, us, you name it, and you want just this anonymous sea of sagebrush.

Chris: As we traverse the caldera with Katie, we move through an extraordinary diversity of habitats. From exposed arid hilltops, to lush wetlands, to soft meadows where the round mounds of sagebrush are nestled among tall clusters of grass rippling in the breeze.

Katie: That is basin wild rye. This is a native bunchgrass too: squirrel tail. That is an indicator of sort of deeper soils, that taller bunchgrass.

Chris: The presence of sagebrush and other native plants has been diminished from what it used to be, in large part due to cattle ranching.

Katie: Back in the 50s and 60s, and 70s into the 80s, there was a huge manipulation of sagebrush for the sole purpose of livestock forage where BLM went in and just aerially herbicided sagebrush to get rid of it and planted exotic cattle forage grass.

Chris: In recent years, wildfires have intensified this habitat loss, burning large areas of remaining sagebrush and contributing to the spread of aggressive plant species such as cheatgrass.

Despite these disturbances, the sagebrush steppe, as ecologists call it, is still home to many living beings. One of the most well-known species that live in this biome is the greater sage grouse. A favorite subject of wildlife photographers, the birds are famous for their displays during mating season, when males gather in clearings called leks and perform elaborate dances and songs to attract females.

Katie: They're very traditional. They'll come back to the exact same spot year after year. But one of the things you see here is there's no big rocky outcroppings right here. You can sort of see all around.

Chris: We're standing in the middle of what is called the Montana 10 Lek, one of the best studied and most important sage grouse leks in North America.

Katie: The sage grouse will be out here, depending on the year early March but certainly by mid March, out here displaying and they go to early May typically. And so the males come in every day, display, and then the hens just sort of fly in or walk in and the males get even more excited and then the hens fly away and nest. And sometimes there's enough time for them to come back, mate again, lay another clutch of eggs.

Chris: A report by the U.S. Geological Survey in 2021 found that the number of sage grouse has declined across its range by 80 percent since 1965, with even greater decreases in the Great Basin region.

Sage grouse, as Katie explains, are highly sensitive to disturbances in their habitat. The Thacker Pass Lithium Mine is located less than a mile from the Montana 10 Lek. Even if the mine doesn't directly impede upon the lek, the sage grouse may still be disturbed by the noise that carries far on the open plains.

Katie: That's one of the things with sage grouse. Not only do they need a landscape, they're very sensitive. They need a minimally disturbed landscape.

There was work done in like 2010, 2013 in Wyoming with oil and gas development. Truck noise going in and out and in and out having a real impact on the number of birds using leks. And then there's been some more recent work done on geothermal development and geothermal plants. There were lek declines in association with geothermal development. The noise and the visual stimuli — just the whole change in activity.

Chris: The intact sage grouse habitat in the McDermitt Caldera is the last of its kind remaining in the Great Basin. But, while sage grouse are one of the region's most beloved and well-known species, the caldera is home to many birds. On our trip, we saw a golden eagle perched on the jutting rock formation, and heard the sounds of songbirds among the vegetation.

Katie told us how crucial the brush habitat is for these and other birds.

Katie: It's called the sagebrush sparrow. But it nests sort of in that lower elevation Wyoming sagebrush. And there's also another sparrow — lark sparrow — that nests here in the caldera too. But the sagebrush sparrows, they're super thick over in the Jindalee claims area. So many sagebrush sparrows.

Out here we have black-tailed jackrabbits, cottontails, and also some pygmy rabbits.

Chris: This catalog goes on and on and includes multiple species that are critically threatened or endangered.

Katie told us that the Endangered Species Act, or ESA, is one of the few laws that can protect land from mining development. But it's far from perfect. Listing animals and plants can take many years, sometimes impeded by political interests. By the time a species is listed, it may be in a much more precarious position than when the process started.

Katie: The political weight of the livestock industry, oil and gas, and mining prevents listing. We have the congressional writers that say, “Thou shalt not list sage grouse,” attached to these big blobs of legislation that have pork-barrel projects for everybody there. No! If they were operating purely on science, not even science or common sense, sage grouse would have been listed 10, 15 years ago.

Chris: This desert landscape is beautiful to witness and teeming with life. But as we've already heard, it is neither pristine nor untouched.

It is actively inhabited and supports diverse livelihoods. In addition to their use by ranchers, these lands are also actively used by Paiute and Shoshone people who gather medicine, hold ceremonies, and hunt. Day Hinkey, a member of the Fort McDermitt Tribe, and Justina Paradise, a tribal councilwoman, both of whom you heard from at the beginning of this episode, describe a few of the specific uses of sage.

Day: My uncle would put these in his nose when he'd go hunting. He stuffed these in his nose.

Justina: You can also use that to rub yourself with and so they won't smell your body odor when you hunt the deer.

Chris: This kind of ecological knowledge is central to the region's Indigenous cultures, passed down generationally over centuries of evolving conditions and practices. But it also is subject to loss when the environment changes, or there are other barriers to the continuation of cultural practices, as Myron Smart, a Paiute Shoshone descendant, reflects.

Myron: Deer brush. When it first comes out like that, dig it out. That's good for asthma. You boil, you know, you take the root out, then you break it up like that, then you boil it, and then you let it sit for a while, and then you drink it. Then you go into the sweat lodge, and then pray about, you know, your breathing.

Because back in time, my mom used to have asthma really bad, so my grandpa's the one that helped her. She always talked about that. My grandpa was the one that made prayers for her to where she was alright for the longest time. All the way up until like maybe about seven, eight years ago, maybe nine years ago, she passed away too. I don't even remember some of this stuff, the Native names.

Chris: As they share their ties to the caldera, Justina, Myron, and Day all express their concerns that mining will make it even more difficult to practice these Paiute and Shoshone ways of life.

Justina: I know for sure if it does happen, if it goes through, then our people are not going to be able to come out here and collect their medicinal plants. It's going to be all gone.

Chris: It's going to be all gone. In addition to being concerned about the area's flora, the Indigenous communities here worry about what might happen to the fauna. Hunting animals remains an important part of their culture. Here is Day and Justina reminiscing about their childhood foods as we ate lunch together in a grove of aspens.

Day: My grandma used to make jerky soup. Oh, man, that was so good. She put potatoes in it. Boil that jerky for so long, kind of get it soft. Potatoes in it, onions.

Justina: Yeah, I don't remember eating like hamburgers and stuff until probably, I was in elementary. Because I was always eating deer, rabbit, whether it's breakfast or lunch or dinner. And then our grandpa, he had a garden where we had to have vegetables. An apple orchard where we used to go eat apples.

Chris: One important food source they describe is the Lahontan cutthroat trout. This fish, which can weigh more than 40 pounds, is native to the tributaries of ancient Lake Lahontan.

15,000 years ago, Lake Lahontan would have covered thousands of square miles. The land we were standing on inside the caldera would have been inundated by hundreds of feet of water. Most of the lake has since dried up, leaving behind only fragments of its former vastness. The fish remain in the smaller tributaries, including Pyramid Lake and the streams that crisscross the caldera.

Day: So how they used to fish those a long time ago, is they would walk in the creeks and they'd put their hands and walk along. They'd feel the fin and they'd go along and they'd feel the fish. All the way up until they got to his gills and then throw them out. We used to do that as kids, walk along the creeks. I remember us doing that one time. And that's what we were taught from the old people.

Chris: We learn more about the fish from Paul Ruprecht of the Western Watersheds Project, an organization that advocates for greater protection of public lands, especially from cattle grazing, which they see as a threat to the region's biodiversity.

Paul: They're a really beautiful fish that have an olive body and rose colored gill plates. And then like other cutthroat trout, get their name from a crimson slash in their throat area.

Chris: An ecologically significant species, the trout has long been of importance to the Indigenous groups of the Great Basin.

Settlers nearly wiped out the Lahontan cutthroat trout during the 20th century, causing total extinction in some lakes. The fish was listed as an endangered species when the ESA became law in 1973. Five years later, the species status was changed to the less severe category of threatened, a designation it still carries today.

Paul: This is a species that used to be a lot more widely distributed, and now it's really relegated to just very short sections of headwater streams where the conditions still exist for it to survive.

It needs colder water and clean water and cover. Those are things that are directly impacted by land use like livestock grazing.

Chris: But mines need to have constant access to water. Lots of it. Hard rock lithium mining requires enormous volumes of water for the mine's operation. The environmental impact statement for Thacker Pass lists the water use in acre feet and gallons per minute, units that allow the mining company to report water use in units that seem small.

Extrapolating from those estimates, though, the mine is expected to use 1.7 billion gallons of water per year operating at full capacity.

On top of this direct water use, Lithium Nevada anticipates having to dewater the mine, a process of removing naturally occurring groundwater to allow for mining, at a rate of 55 gallons per minute. In a region where water is already scarce, the risks that come with extracting such large quantities of groundwater are significant.

Paul: There's a lot of concern, I think, with these individual populations of Lahontan cutthroat trout in the Montana Mountains, that impacts from Thacker Pass Mine or other mines could dewater springs or water tables that feed these streams and really have an impact on these fish populations.

Chris: For Paul and others, the trout is a keystone species whose vulnerability to watershed degradation speaks to the potential cascading consequences of the mine. Despite these concerns, the final environmental impact statement determined the mine did not pose sufficient risk to the cutthroat or other protected species to prevent its construction.

Ecologists and Indigenous communities are not the only ones whose worries about the mine are not allayed. Ranchers are also concerned about its implications for water. Despite historical tensions between conservationists and cattle ranchers, whose grazing practices can displace and harm native wildlife, new alliances are forming in response to water issues around the Thacker Pass Mine.

Despite markedly different land use values, many conservationists and ranchers agree that the mine threatens their relationship with the land.

Edward: My name is Edward Bartell. I ranch near the Thacker Pass mine site.

Chris: Ed filed a lawsuit against the Bureau of Land Management, or BLM, in 2021, soon after the agency granted its record of decision approving the Thacker Pass Mine. He alleged that previous studies violated sections of both the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA. As a rancher, he's concerned about his wells running dry. His livelihood depends upon having access to clean, reliable quantities of water.

Edward: If they start dropping the water table, it's not really economical to haul water out there because it's just miles and miles across desert. If they drop the water table underneath our private lands out there, we've got close to a thousand acres that the vegetation depends on. So, that would be devastating for running cattle, but also if you have a pretty green meadow versus barren dustbowl, it dramatically affects land value.

Chris: In fact, Ed alleges that exploratory drilling and monitoring wells have already dropped water levels.

Edward: The mine itself is about three miles away, but the well is right within our BLM grazing permit. And in fact, when they test pumped the well for merely two and a half days, it had already started showing drawdown in our stock water well.

So I mean, they're not theoretical impacts. It's clearly going to impact it. The argument is over how much.

Chris: Ed wasn't opposed to the mine at first, but after failed attempts to gain a hearing with both the government and Lithium Americas, he filed a lawsuit.

Edward: The mining company and the Bureau of Land Management, they often do what are called work plans and they frequently go well outside of the area that they've disclosed where they're going to do drilling. And the BLM has tasked the mining company with doing all the baselines.

And so it's obviously in their interest to say the springs aren't flowing. And of the eleven of our springs that we held water rights to, that they measured, nine of them have clear errors, I mean blatant errors, like saying there's zero flow when they flow every year all year round, or saying that they're ephemeral, which means they go dry a short period after rainfall, when in fact they flow year round. So by understating the flow, they can absolve themselves of culpability when they start drying things up.

Chris: We personally saw the impact of the lack of water on our trip. We had one other thing to see on our caldera visit: the Kings River Perg. This tiny spring snail, mere millimeters in length, is only known to exist in 13 shallow springs scattered across Peehee Mu’huh and the Montana Mountains.

Terry Crawforth, the retired former director of the Nevada Department of Wildlife who now lives in the Kings River Valley just north of Thacker Pass, offered to show us around the perg's home. He has long known Katie Fite, who you met earlier in the episode. Both share a passion for local birds and keeping a watch on them.

Terry: When I worked for the state wildlife department, I worked at Fish Hatcheries, and then I was a game warden for almost 20 years and then was a supervisor in Elko and that's where her and I ran into each other the most because she was with Idaho at the time. And then when I became director we didn't have much to do with each other except in ugly meetings with government agencies and things like that.

She came into my place one day here a couple years ago. My mom and family and everything was there. She had found an eagle, a golden eagle, that had hit a power line. And it was still alive, so she brought it to me. And it didn't make it, but that's how I got started with Katie again. My family knows her as “the Eagle Lady.”

Chris: When we went with Terry to check out a spring where he had previously seen spring snails, the spring was mostly dry. One factor was a time of year, late June, but Terry also shared that the springs have been dry for weeks as he and Paul Ruprecht had seen together.

Terry: I've never seen this not running water until I had Paul here the other day. First time I've ever seen it dry. Yeah, normally there's water running right across there.

Chris: This was a common theme of our time with Terry. One dried up spring or stream after another.

Terry: Well, still dry.

There's a little bit of a spring up there, and I had not been up to that to see what it looks like, but normally there's water running right here.

When I brought Paul here, I was stunned.

Up above there where the meadows start it's plum dry and I've never seen it that way. I've been messing around in this country for 35 years.

I've never seen that dry. This little spot where the pyrgs are — never seen that dry.

Chris: While Terry pointed us to a number of possible causes, he's most worried about the implications for the King's River Perg that these evident changes already portend. Regardless of the origins, one thing is clear: water in this already dry region is a scarce resource shared by many, even creatures beyond the caldera's perimeter.

Terry: I went past Thacker Pond one day and stopped and I went, that's a swan. A swan, that's not long enough for a swan to take off.

So I stopped and looked at it and it had a collar on it. So I got my spotting scope out and was able to read the number and I called the waterfowl guy in Reno and said, “Hey.” And he said, “I know a guy that will be very interested in finding out about that bird up in Alaska.” So the guy called me the next day, and that swan had left by then.

He called me the next day and said, “Now where is this?” And he got on and figured out where it was. He said, “That bird left Alaska two days before you saw it. That's 4,000 miles.”

Chris: From the wildflowers on the ground to the eagles in the sky, from the aspen groves to the towering mountains, the caldera, far from being empty, is rich with sights and sounds if you take the time to observe them. This is a truth that people living in the area have long been trying to tell. How did the caldera go from a region with so much life to one that is under threat?

In the next episode, we will consider the longer histories and larger contexts that have allowed lithium mining to take hold.

Nate: Mining for the Climate is a co-creation of Nate Otjen, Jessica Ng, and Juan Manuel Rubio, and it's a production of Blue Lab at Princeton University.

This episode of Mining for the Climate was written by Christopher Bao, produced by Christopher Bao and Nate Otjen, and edited by Jessica Ng and Nate Otjen.

Our research and production team includes: Christopher Bao, Jose Santacruz, Jessica Ng, and Nate Otjen.

Music for this episode was by Pixabay and Xeno-Canto. Find it at pixabay.com and xeno-canto.org. Sound design is by Gianna Imparato.

Mining for the Climate was made possible by funding from Blue Lab, the High Meadows Environmental Institute, the Humanities Council, and the Office of the Dean for Research at Princeton University. Ramapo College generously provided faculty research funding.

We would like to express our gratitude to the following people for their generosity and kindness: John Hadder, Ian Bigley, Susan Frey, Day Hinkey, Myron Smart, Justina Paradise, [00:31:00] Gary McKinney, Katie Fite, Dorece Sam, Edward Bartell, Kassandra Lisenbee, Terry Crawforth, Autumn Harry, Chanda Callao, Daniel Rothberg, Ryan Houston, Paul White, Kate Berry, Eric Nystrom, Simon Jolette, Ka’ila Ferrell Smith, Josh Dini, Carolina Muñoz-Saez, Ehsan Vahidi, Paul Ruprecht, Rick Eichstaedt, Chrissy Klenky, Nick Erruty, Patrick Donnelly, Philip Ruprecht, Will Folk, Glenn Miller, Mike Visher, Rich Stone, and Dave Mendiola.

At Blue Lab, we especially thank last season's Mining for the Climate team: Juan Rubio, Grace Wang, Max Widmann, and Alex Norbrook, along with the lab’s leadership, Allison Carruth and Barron Bixler and fellow members Jamie Collins, Mario Soriano, and Asela Perez Ortiz.

And at the High Meadows Environmental Institute, we thank Emily Ahmetaj, [00:32:00] Stacey Christian, Kathy Hackett, Nathan Jesse, Ryan Juskus, Zack Kaado, Heidi Mihelich, and Laura Matecha.

And at the Effron Center for the Study of America, we give special thanks to NicQuwesha Toliver.

Outsiders and those who are not connected to the land often see the desert West as barren and unpopulated. However, Indigenous peoples and other beings have coexisted with the land since time immemorial. In this episode, we hear from Native and non-Native people who have deep connections with the McDermitt Caldera. Together they are grappling with what the potential loss of these attachments means and fighting to protect them.

Episode Credits

- Written by Christopher Bao

- Hosted by Christopher Bao

- Sound design by Christoper Bao

- Research and production team: Nate Otjen, Jessica Ng, Christopher Bao, and Jose Santacruz

- Music by Pixabay (www.pixabay.com) and Xeno-Canto (www.xeno-canto.com)

Copyright 2025 Nate Otjen, Jessica Ng and Blue Lab. All rights reserved.

The Mining for the Climate team eats lunch in an aspen grove in the caldera with Day, Myron, and Justina. Photo by Jose Santacruz.

Katie Fite holds a sage grouse dropping and explains that the bright color indicates a diet of yellow wildflowers. Photo by Chris Bao.

Episode 3: Land Access

Mining for the Climate Season 2, Episode 3: "Land Access”

Full Transcript

[00:00:00] You're listening to Mining for the Climate. This is Alex.

Mines are like living organisms. They require a living space.

They need to consume certain things to survive, like chemicals, energy, water. As their metabolism ramps up, mines crush rock, absorb desired elements from it, and discard their waste in piles of boulders and streams of cloudy water. Thinking about a mine in this way brings order to its many processes.

But the shape and nature of this metabolism is not always evident. As the history of mining teaches us, mining companies tend to keep some aspects of their operations out of sight. In response, those who resist these operations work to uncover the actual shape of the mine, and its impact.

Throughout this struggle, the contours of each mine are constantly redrawn. [00:01:00] So in this episode, we pay attention to the power inherent in the act of obscuring, and in the act of revealing.

This is Mining for the Climate, episode three.

It's a hot June day. We're driving to Piedmont Lithium's outpost along the winding Dallas Cherryville highway, passing sign after sign declaring "Stop Gaston County Pit Mine.”

We pull into the gravel lot outside a one-story warehouse with Piedmont Lithium's logo on a sign outside. An employee beckons us in. Inside an air-conditioned room filled with boxes of rocks and presentation slides on easels, we introduce ourselves to three Piedmont employees who we'll sit down with for the next two hours to talk about the mine.

Yeah, so Piedmont Lithium started back in 2016 by our now chief geologist Lamont Leatherman who grew up just a few miles north of here in Lincoln County…

When we [00:02:00] speak with these representatives, our first question is about the impact of the mining pits, the places where Piedmont would blast and move rock.

As I was mentioning before, about 25% of the acreage is mining. So these are the four pits that we plan to have and we will mine them south, east, west, and north and so that's where mining activity is slated to happen. We will convey material from the mines to the concentrator plant and then also take it to this area here which is what we call our waste rock pile. So that's just after we've blasted and gotten the spodumene-hosted rock we're going to send any of the waste rock here to be stored.

The open pits are the most visible parts of the mine, where many of its processes start. They are, in a sense, the mouth of the mine. Let's begin here.

Part 1: The Mine's Mouth

Piedmont Lithium plans to build an open pit mine. Think a ribbon-like circuit that spirals down into the earth, heavy haul trucks that [00:03:00] rumble around the site, and timed explosives that rip apart tons of solid rock, tearing the earthen cavity even wider. In Piedmont Lithium's case, this is the mechanism that would bring the raw spodumene, the lithium bearing rock, up for processing.

When we ask about what noise, light, or dust impacts the mine might have to nearby residents, Piedmont representatives describe a clean, almost invisible mine that's isolated from its neighbors.

Juan prompts Monique Parker, Piedmont's Senior Vice President of Safety, Environment, and Health, to talk about the issue.

Obviously, there's population around. There are neighbors. If they really want to stay in their farms, in their houses, what, what kind of options do they have?

For all intents and purposes, if there’s a neighbor outside of our mine permit boundary, they can stay in their home. Our activities don’t change the livelihoods of those around them in a negative way in that regard. There’s very little things that would prevent them from being able to stay on their properties if they’re outside our mine permit boundaries.

[00:04:00] You can understand how their, perspective on the land will change, right? More light pollution, potentially dust, changes in the landscape for sure, perhaps fences going up…

Well here’s the thing, although those things may be true cuz we are gonna have fences around our property and those types of things, but we’re also gonna have trees. So this area is rich in trees and other natural resources so we’re gonna have various berms and other protections where the reality of it is, they may never know we’re there.

Erin and I, our children went to a middle school. There was a mine right across the street from them. I didn't know it, and so I really didn't, but at one point I was driving by and it was winter.

That's Erin Saunders, Senior Vice President of Corporate Communications and Investor Relations,

I kind of glimpsed something between trees. And I went home and pulled up the map. [00:05:00] And apparently for 17 years, I've been living less than two miles from a giant quarry. I, I had no idea. And I don't, I don't think people realize that if you can't see it, you can't smell it, you can't hear it. And there are the trees and the berms and, and everything.

To Erin Sanders, the quarry next to the school was almost invisible. Piedmont reckons their mine will have a similar visibility.

As we’re mining, there obviously is a potential for dust to be generated and created. We will be using water suppression to minimize and control dust as our dust control suppression system.

The same, Monique says, holds true for the chemical processing plants which convert spodumene into lithium.

So we have a ton of dust collectors around our chemical process where those dusts will be captured, and then we have an air permit that minimize what we can emit. So all of those are captured with our dust control systems. We have wet scrubbers that will all manage the dusts that come from our process.

[00:06:00] Erin also describes their conveyor belt system, which will transport blasted rock from the pits to the concentrator plant.

We're also going to invest millions of dollars in an enclosed, uh, conveyor belt system. As you probably know, trucks are what can kick up dust, you know? So to minimize the number of trucks, we're going to use that conveyor system.

It also helps on noise, as well. You’re not having haul trucks going around on public roads. We can have electric conveyor belt systems going through our property.

That's Emily Winter, Exploration Geologist and Community Relations Specialist.

So, forest buffers, electric conveyors to haul blasted ore, and dust suppression systems. These are the strategies that Piedmont says will make their mine near invisible.

But Lisa Stroup, a cattle rancher and former mine employee living close to Piedmont's property, has a different projection. On the wide porch [00:07:00] which wraps around her house on the ranch, I ask,

They told us that, you wouldn't be able to tell it’s there.

Really?

She seemed, almost, at a loss for words.

Okay, just look this way. You see all these trees? There is a hill, right? A natural hill full of trees. It is a humongous forested area. That's almost two acres between us and the mine.

That's the stone quarry managed by Martin Marietta.

And this entire property, our home, our trees, even back up here was coated in dust. I don't buy it. I don't buy it. I don't see how they can do that when the industry leaders can't.

Lisa is suggesting that if Martin Marietta, an experienced mining company, couldn't fully control their dust, how could Piedmont, as a new mining company, claim to be able to control it so well?

And you know, we saw how hard they worked to try. It wasn't that they were just [00:08:00] not trying, they were pumping thousands of gallons of water spraying down this ore as they're extracting it and hauling it, doing the best they really could to minimize it. I hate to think what it would've looked like if they hadn't, but there was still dust. There was still noise, you know, even after they stopped blasting and they were just hauling the aggregate from the mine.

I was working third shift inside my home. All the windows closed. All the doors closed. I can hear their mine trucks, I can hear their conveyor belt and the be end and the, you know, when they dumped the load, the crash of the boom when it landed back down, I could not sleep. It was absolute torture.

Lisa lives less than a mile away from the Martin Marietta quarry. At the time of writing, the closest house to Piedmont's site is just 318 feet away.

The former miner we spoke with last episode, who requested anonymity, actually [00:09:00] worked at the Hallman Beam lithium mine, which became Martin Marietta's quarry. When Piedmont arrived in town, he realized he was living next to their purchased land and decided to sell his house after realizing what this proximity would mean.

They had bought every place around me.

You know, you can't live around in the noise. Hm. You know? You know what I'm saying? Just can't. I know. I used to work in that one right over there when I was 18 years old.

It's true that dust suppression systems do work to minimize the amount of dust kicked up by mining operations. It's also true that many mines aren't noticeable to someone driving by them. We don't know what Piedmont's mine will look or sound like.

What we do know is that residents of the area are struggling to find out, and their homes and livelihoods are on the line.

Part Two: The Stomach

Piedmont proposes to build two processing plants to extract the lithium from its surrounding rock, and then convert it into a battery grade [00:10:00] material. As with dust and noise, Piedmont also stresses how this process would be as clean as possible. They suggest it will be a departure from the older model of dirty, chemical intensive, and polluting mines.

Here's Monique:

I will talk about some of the historical means of getting to this final product. Traditionally, producing lithium hydroxide has been used with a sulfuric acid leaching process, and so that’s the traditional means which creates toxic waste, it’s hazardous to work around.

Most hard rock lithium mines still use acid leaching, which dissolves out the lithium from the rest of the rock to collect it into a usable product. Leaks and drainage from these acid processing activities have damaged surrounding environments. So instead, Piedmont intends to move to a different process altogether.

The technologies that we’re looking to use actually uses steam. We will do the transition from spodumene to lithium carbonate using pressure.

Monique is referring to Piedmont Lithium's [00:11:00] use of the Metso Ototec conversion process. This process uses soda ash and other alkalines, along with pressure, to leach out the lithium and convert it into battery-grade lithium hydroxide. It employs alkalines instead of sulfuric acid.

So these are some of the things that we’re doing, and we’ve taken these approaches to have a more sustainable operation. Obviously, we want to minimize how much toxic waste we’re generating. We want to make sure the operations are safe for those that have to work around it.

In fact, the CEO of Piedmont claims that this process helps...

to make our operations the world's most sustainable lithium project. We've shifted our chemical plant process to be entirely sulfate and acid free. That makes it better for us. It makes it better for the neighborhood and everyone else, and from an emissions perspective, it's far superior.

This all sounds pretty compelling. A clean and safe chemical system. But in their narrative of cleanliness, what does Piedmont emphasize, and what do they downplay?

If you ask Lisa Stroup, she [00:12:00] sees elements of concealment, having already done research into Piedmont's original 2021 mine permit application.

You read in the report, there's gonna be tanks of sulfuric acid and diesel fuel and whatnot at this concentrate plant.

They told us that they were not going to use the sulfuric acid.

Well, they either lied to you or they lied in their permit application because it is in the permit application. And this is another misleading thing that Piedmont has a tendency to do.

Let's pause for a moment. If you look at the section of the mining permit that Lisa's talking about, you see that Piedmont writes that they'll store, among other things, some frothers and floculents and, sure enough, “sulfuric acid.”

It's right there. Piedmont also lists some other reagents used in the concentrator plant, which is the plant that removes some of the excess rock around the lithium. They list hydrofluoric acid and kerosene. [00:13:00] Curiously enough, in the reagents for the lithium hydroxide conversion plant, which is the plant that actually converts the lithium ore into battery grade lithium hydroxide, the permit lists both sulfuric acid and hydrochloric acid.

So how could we hear from Piedmont that there was no sulfuric acid, even though the application includes it?

They were talking about the hazardous toxic chemicals that would be on site and would be utilized for the concentrate mine operation, not the conversion, but the concentrate mine area. They're only taking you to the end and saying, no, we're not using acid. Okay, so go back and look at the, the mine permit applications specific for the concentrate mine process.

Let's clarify this. Lisa draws a distinction between the concentrator process, which collects the lithium, and the conversion process, which turns it into usable lithium hydroxide. She says that Piedmont claims their [00:14:00] conversion process doesn't use sulfuric acid, and that they use it in their concentrator process without much advertisement.

In our conversation with Piedmont, too, we hear them talk about their new conversion process, and we don't hear them mention the other processes involved in concentration.

Here's Monique:

Because, again, we’re not using sulfuric acid. We’re using pressure leaching and so the natural pH is very different than a normal, traditional wastewater that you get for traditional lithium hydroxide conversion.

“Lithium hydroxide conversion.” She draws attention to this conversion process without bringing up the concentrator.

A more recent document, from June 2022, nuances this distinction when giving another description of Piedmont's chemical processes. Here, most of the chemicals in the concentrator process are consistent with the initial 2021 mining application, except that Piedmont doesn't list sulfuric acid among them like they did in 2021. [00:15:00] It's the same story with the conversion plant. No sulfuric acid.

That's because they list a third chemical sub-process that we didn't hear about in our conversation with Piedmont: a separate “byproducts production" process. This part takes some feed from the main concentrator process and extracts feldspar and quartz to then sell. It's here where Piedmont lists the sulfuric acid, and the hydrofluoric acid, and the kerosene.

In a later email from September 2023, Piedmont gave another answer, that, “Some sulfuric acid may potentially be used for cleaning purposes in the on-site wastewater treatment and the crystallizers.” A summary of that correspondence is available on the Mining for the Climate webpage at https://bluelab.princeton.edu.

So, is the chemical process of this mine really cleaner than other mines? Probably, in many respects. The METSO technique does have potential, and it likely would mean the elimination of a lot of sulfuric acid.

[00:16:00] But, we found the discrepancy between the first descriptions that Piedmont gave us about their chemical process, and their mining documents and later comments would show different mechanisms, particularly telling.

How does this choice of framing contribute to the image that Piedmont's mine is cleaner than the rest? Is their plan as simple or as clean as they tell people publicly? Is it as clean as what people demand from the energy transition?

Part 3: The Blood of the Mine

Most mines use water to extract minerals and wash away unwanted particles. Piedmont will use a considerable amount of water in these processes, but before the company uses the water for mining and refining, they need to address a more immediate challenge.

As machinery digs ever deeper into the mine's four open pits, it will quickly encounter rock below the water [00:17:00] table, meaning rock that is saturated with water. To prevent its pits from flooding with this water, Piedmont will suck it out, at 2,125 gallons per minute.

The issue is Piedmont's mine would not be the only place drawing water from the ground. Most nearby residents use well water because there isn't a municipal water system in the area. Could Piedmont deplete these residents' wells? And how does that affect the image of the clean mine that Piedmont projects?

Here's Monique again:

There will be minor impacts to the water table and the immediate areas we know for sure. How far those expand are what the studies will tell us. But if you think about water table, and I’m sure you all are knowledgeable and understand this, but a water table is not like a bathtub where you put a plug in and it’s all gonna drain out. With the geology that we have, there are fractures and seams and different ways that water moves within rock. Once we open one area, it doesn’t necessarily impact the full groundwater level or table in a certain region. It is very much based on the geology underneath the ground. And so our studies will help us understand that better.

[00:18:00] In Gaston County, the bedrock is highly impermeable, meaning water only flows through bedrock in minuscule fissures and cracks.

Monique's assessment of the impact to the surrounding area follows from a couple of Piedmont studies conducted on possible groundwater depletion.

Some of these studies didn't go exactly as planned, as some of their permit application documents show. In one study in which Piedmont tested maximum potential for pumping water out of the ground, the test pump they installed didn't have enough power to sustain a full test. Heavy rainfall in addition to Hurricane Michael shortened that study and prevented Piedmont from installing a new pump, which cut the data gathering process short.

Regardless, the study found that beyond the mine site, predicted depletion of nearby wells from their mining activity would average 6 feet, with a minimum of 0 feet and a [00:19:00] maximum of 39 and a half feet. To try to mitigate this potential impact, Piedmont came up with a plan.

Here's Monique:

So I’ll address the impact to neighbors first. So one of the things that we had to do was create a well mitigation plan. So if we impact a neighbor, what are we gonna do? We’ve offered three solutions. One, we’ll dig ‘em a deeper well. Two, we will connect them to municipal water. And our third — is kind of our intermediate is — we’ll make sure they have water during a period in which we’re getting them the one of the options we have, whether that’s through various means that makes it available and easy for them to obtain. That’s our mitigation plan in those impacts.

To the governing bodies that are overseeing Piedmont's permit application, this might sound reasonable, but following their previous interactions with Piedmont, residents we spoke with aren't reassured. When we talk with Tom about possible water depletion before we sit down with Lisa, he actually calls her up to show us her read on the situation. [00:20:00]

She seemed skeptical.

Piedmont's solution to that is they will hire an outside representative and if they can prove that Piedmont did the damage, then they may either bring in bottled water…

On their mining permit, Piedmont offered to supply water tanks to affected households.

Or they may dig a new well. Well that's really fruitless. If the groundwater is contaminated, what good is a new well?

Lisa's referring to water contamination. Groundwater level isn't connected to water contamination. So this is a separate issue that we'll come back to later. Anyway, Tom says to Lisa:

You remember the two other options that they provide as solutions?

Third one was they would connect you to municipal water.

Then, Tom prompted one final option, which Piedmont didn't bring up to us.

And the nuclear option is if all else fails in good faith… Oh. Or they would purchase the property, which would be worthless if you have no access to water. [00:21:00] Which is their end goal because you know, so many property owners don't want to relocate and don't want to sell like us, we're a beef cattle operation. We have over 200 head of cattle.

We also have grain and food and fiber crops that we plant. It's more than just our house that's here. It's our business, it's our livelihood. And where are we gonna find another 400 acres to farm?

Piedmont's water mitigation plan could reduce the severity of the possible impact to residents' water supply. However, these residents are angry that Piedmont suggested these solutions without consultation, and that the solutions they present don't reflect residents' lifestyles or protect their dignity.

Part Four: Keeping the Pulse

It's not always clear how a mine's body works, so systems must be kept in place to monitor its functioning.

A question [00:22:00] crucial to environmental justice is, who does the monitoring? Who keeps the data? And what are the consequences if something goes wrong?

Piedmont plans to install monitoring systems in nearby rivers to detect any impact to water quality or quantity. The company would then be in charge of reporting any potential issues.

We’re gonna have monitoring wells around our property, so the reality of it is we will know before a neighbor knows primarily that there will be an impact cuz we’ll be measuring the levels of that water continuously to understand if there’s any impacts on our property boundary before it leaves our property. So there will be continuous monitoring of all water — on property, off property — as we go through our process to ensure that there’s no contamination of water in sources.

If Piedmont monitors effectively, it would help protect nearby residents and their drinking water. But Lisa's not convinced that this would be the case. Here's her in our conversation with Tom.

It's my [00:23:00] understanding that the way it is set up now, the biggest portion of control the state has, and the biggest, you know, argument that we will have is in this pre-permit phase. Once they, sign off on the approved list of okay, you've agreed to these terms, it is then up to Piedmont to, create the samples and generate a report. However, it is purely Piedmont's word. From my understanding, unless there is a violation of some sort, the state themselves do not test those parameters.

Lisa isn't the only one looking into Piedmont's monitoring system.

They're gonna tattle on [00:24:00] themselves. Right.

That's Locke Bell, one of the residents we spoke with last episode.

Hey professor, can I grade my own paper and just turn in what I made? Hey, if I could have done that, I probably would've done better in school. Yeah.

Locke was looking through the monitoring plan in Piedmont's mining permit and saw something that gave him pause.

In their application with the mining commission, it says that they'll have retaining ponds.

Piedmont would hold much of the water they pump out of their pits in a series of retaining ponds scattered around the mine.

So Piedmont will monitor their ponds. Okay? We don't need EPA. DuPont monitor what you're releasing. Duke Energy, which had the big coal. I don't know if you know about the coal ash. Y'all monitor yourselves. Exxon Mobil. Y'all, y'all, y'all monitor and report back.

Oh, all you people fracking. [00:25:00] We trust you to let us know.

But that's what they've got here is that Piedmont — on the toxicity, on the pollution, on everything — will monitor themselves and either do quarterly or annual reports. But you see what I'm saying? You would never ever anybody do that.

Piedmont says that they'll monitor their tailing pond pH and depth monthly, not quarterly or annually. But not even the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, or DEQ, is satisfied with that. In May 2023, DEQ, who is overseeing Piedmont's application process, asked why only pH will be tested, and why monthly testing instead of continuous monitoring is sufficient.

Responding to this concern in an email from September 2023, Piedmont stated that they will be, “evaluating other parameters that are tested for similar operations, and [00:26:00] will be providing an updated monitoring plan in our response.”

In the event that a well becomes contaminated from mine operations, Locke and Lisa are skeptical that Piedmont would let people know. And Lisa isn't sure how residents could verify Piedmont's monitoring or hold them accountable for water quality issues, especially given her community's remoteness.

So let's just say we have water, but they've contaminated it. No one tests the well water. It's up to each owner to test the well. And it can cost several hundred dollars every time you do and take several months for you to get the results.

You're paying for the testing. You're waiting for the analysis. That goes with any industry. It's not just this mine, it is a self-report.

Piedmont emphasized in their September 2023 email that, in the event of a contamination issue, they have, "highly experienced mining, engineering, and safety, health, and [00:27:00] environment professionals" on their team, and "a couple of hundred of the top consultants in these fields" to manage the project responsibly and sustainably.

Piedmont says, don't worry. Trust us. America has the tightest environmental restrictions of any country, you know. Trust us. But trust is very different than verify. We're trying to verify. We want truthful answers. We want them to treat people fairly and then be a good neighbor.

Trust versus verify. Piedmont asks its neighbors to trust their monitoring, but residents feel they have little room to verify Piedmont's data to hold them to account. Piedmont, to them, controls the knowledge of any potential well disturbances, and they imagine the company plans to keep it that way.

Part 5: The Waste

Mines produce waste. A lot of it. In Piedmont's case, once the mine blasts [00:28:00] and hauls rock, once it dissolves and leaches its ore with a cocktail of chemicals, it's left with thousands of tons and hundreds of gallons of waste. In an area with sensitive streams, the safety of the mine's wastewater is a particular concern. Here's how Piedmont plans to manage this wastewater.

When it comes to water from our processes, our chemical plant, all of our processed water that comes from that chemical plant will be sent to a wastewater treatment facility. So there’s not this let’s sit it in a pond and let go to the streams. It will be capture, pre-treated on site, and then sent to the municipal. At our concentrator plant, all of our processed water from the concentrator plant will go through the same process.

Monique is talking about sending pre-treated wastewater from the mine to the Long Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant in Gastonia, a few miles away. And as for the water which flows into the mine pits, either from seams in the rock or [00:29:00] from rain, this water would be pumped into the sedimentation retaining ponds that Locke mentioned.

We will house the water there. We will do testing, understand the quality of it, and then we will either treat it and then release it, or we will release it based on what our permits allow.

Piedmont would release the water from the sedimentation ponds into adjacent streams, not to the wastewater plant, based on their water permits. Here's Juan revisiting Piedmont's agreement with the Long Creek Municipal Treatment Plant.

And has the municipal treatment plant, do they have the capacity to deal with it?

So we’re working with them already. One of the things that we have to have in order to secure our mine permit is the local municipality has to agree that they can take our quantity and our load. They’ve agreed that they can take our quantity and load.

Do you have an estimate of what the quantity is going to be?

We’ve given them an estimate of our quantity of our water and the anticipated load that will go to them and that’s been provided to them and it’s also been in our mine application, our mine permit.

[00:30:00] We noticed that Monique didn't tell us what this quantity of water is, or the anticipated load, in our meeting. She pointed us to the mining permit instead.

We didn't think of it too much in the moment, because if the treatment plant has agreed to take that load, and if they're pre-treating the water to make it safer as it travels to the plant, what could be the issue?

But Lisa and Locke seemed to think differently based on their research.

They have a letter that they have sent to the mining commission, cause I've read it, that says we have talked to the, I wanna say Long Creek or Catawba Creek, one of the treatment plants…

Piedmont's documents identified the South Fork Catawba as the ideal river to carry its wastewater to Long Creek.

And they have said that they can handle 0.284 million gallons a day.

Piedmont put this as their peak wastewater flow on their mining documents.

[00:31:00] Therefore, mining commission, you need to accept this as we have outflow. It's eight miles away. When they did the original application, it said all the water will be dumped into municipal outflow. That's eight miles away.

Let’s be nice to 'em — six if you cut through the country. They don't have any right of ways to do it. So they have a letter and they submitted it saying, “Here's an agreement. Accept this as our having handled the issue of the disposal of the water.”

Locke reacts to their plan in such a way because, so far, Piedmont has not published a full plan of how it will transport its water from the mine pits all the way to the treatment plant.

And where Locke saw an attempt to gloss over the logistics of transporting water that far away, Lisa saw environmental danger inherent in the position to pump it into the South Fork Catawba River.

[00:32:00] These freshwater streams that our children play in, that wildlife drinks from, they're here for everyone's enjoyment, but they could flush it down the streams, processing an affluent channel in the stream, the six miles to the uptake, or eight miles, however, whatever the distance is to the uptake…

Piedmont proposes to release its wastewater into the river and have a treatment plant downstream take it up and process it. That would happen at one of the Long Creek's locations, either in High Shoals, a town a few miles north of Gastonia, or at Apple Creek Business Industrial Park, on the northern edge of Gastonia.